Kendra Koch’s path from stay-at-home mom to advocate for children and youth with complex health-care needs

When her daughter Caelan was born, Kendra Koch (PhD ’17) thought that the surgeries needed for her newborn’s cleft lip and palate were all she had to worry about. But a few months later, Caelan began to experience seizures. She was eventually diagnosed with Aicardi syndrome, a rare genetic disorder that also causes problems with vision, spinal abnormalities, and developmental delays.

“In the end, we learned that we would have a beautiful, vibrant child who could not talk, or walk, or do all the things that parents want their child to be able to do, but who could definitely communicate and influence everyone around her,” Koch said.

Caelan perhaps influenced Koch more than anyone else. Her birth re-directed Koch’s path from stay-at-home mom to grant writer, health-care services innovator and social work researcher. Caelan died in 2014, when she was 18 years old. But her legacy lives in Koch’s work to improve the lives of children and young adults with special healthcare needs.

Landing in Holland

“Welcome to Holland” is a parable written in 1987 by the writer Emily Perl Kingsley, of Sesame Street fame, to describe the experience of raising a child with a disability. In the parable, a couple plans a dream vacation in Italy but somehow the plane lands in Holland instead. Italy stands for the experience of raising a typical child that all future parents dream about. Holland is where parents find themselves when things don’t go as expected; while not a bad place, it’s not the destination they readied themselves for. After the initial shock, Kinsley writes, they must re-orient themselves, buy new guidebooks, and learn a few Dutch phrases to eventually start appreciating Holland.

As Kingsley puts it, the loss of the dreamed vacation in Italy is very significant. But if you spend your life mourning that dream, “you may never be free to enjoy the very special, the very lovely things…about Holland.”

For Koch, landing in Holland meant being catapulted into a world of hospital stays, doctor’s appointments, visits to therapists, and constant search for information about her daughter’s condition and how to best care for her. Very soon, however, Holland became the new normal.

“Normalizing the situation is a survival tactic for every parent of a special-care-needs child,” Koch said. “If you have a child who has breathing issues and twelve seizures a day, you can’t live in a heightened sense of crisis, the nervous system just can’t handle that. You go through that at the beginning, when whatever the condition your child has is a new diagnosis. But then you normalize the situation to survive. You just focus on what you need to do to make things work.”

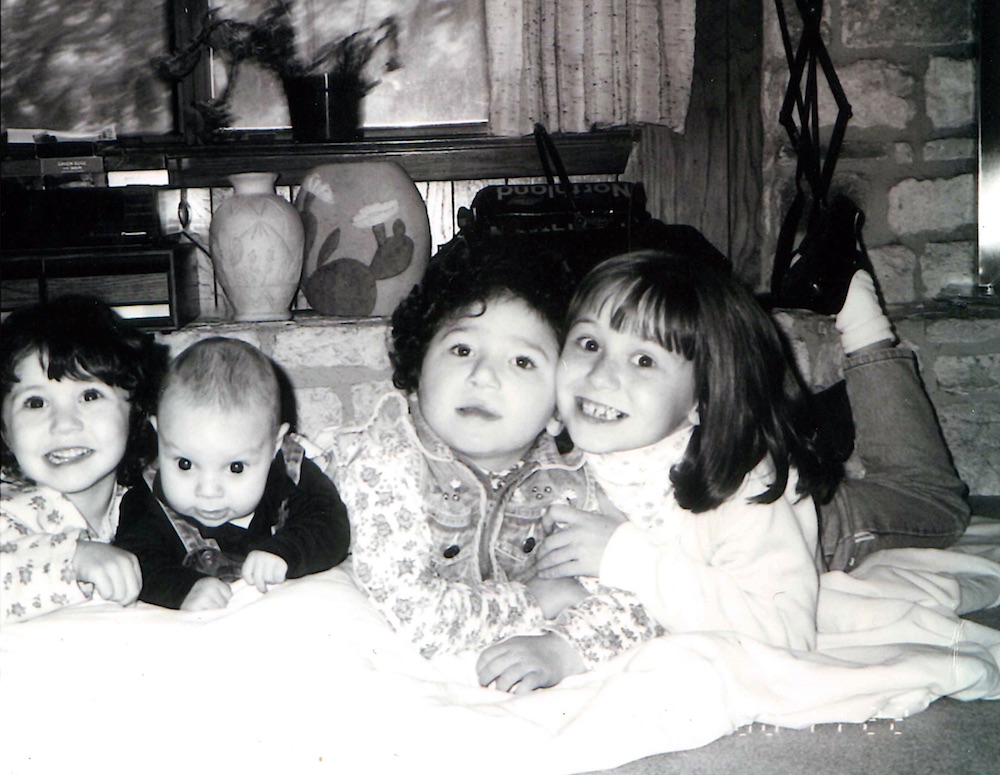

Making things work meant integrating Caelan’s care into her stay-at-home-mom routine, which included homeschooling her other three children.

“We took her everywhere we went: soccer games, choir rehearsals, everything,” Koch said.

Making things work also meant learning, by trial and error, how to manage the complexities of Caelan’s health care.

“Anywhere you went they would ask questions like, how many hospitalizations has she had? Has she tried this or that seizure medication? And so on. And when you are in the middle of it, it’s very hard to keep track of all,” Koch said.

Nowadays, parents like Koch can find many useful resources on the Internet. At the time, she used her own ingenuity to, for example, devise a complete medical journal and daily planner out of binders to help her keep records and coordinate all the service providers involved in her daughter’s care — therapists, physicians, early childhood specialists, pharmacists, insurance companies.

“I was often fighting with insurance companies. It was not unusual to spend days just calling them. My frustration with them in great part led me to the creation of these binders.”

Finding community

When Caelan was 11 years old, she had sepsis pneumonia, a potentially life-threating condition. She became one of the first patients at Dell’s Children Medical Center in Austin.

“What I knew about Aicardi syndrome at that point was that most kids died of pneumonia or an infection. This was Caelan’s first unplanned intubation, and it was a very scary time for us,” Koch said.

Dell Children had launched a pediatric palliative care program, and a member of the team visited Koch’s family. Palliative care focuses on providing relief from symptoms at any stage of a life-limiting illness, and on providing spiritual and social supports to improve the quality of life for both the person and the family. Koch, who was resistant to palliative care at first, found this comprehensive model of care very compelling, and eventually began volunteering with the program by working with other families with complex illnesses to find out what their needs were.

“This was more than a decade ago, and in the world of palliative care children with complex illnesses were still an enigma. Until then, most were born with a poor prognosis and would die early. But because of technology, children who may have died at four years of age were living into their teens or twenties, and the infrastructure needed for decision-making, coordination, and social support was not there,” Koch said.

She found a deep sense of community with the parents in the pediatric palliative care group that sustains her until this day.

“Those mothers are still my closest friends. Some of them still have their children and some not. They are the people I go have a drink with, have coffee with, they understand and there is an incredible bond there,” Koch said.

Forging a new path

The volunteer work at Dell’s Children also opened a professional path for Koch. Her work with other parents inspired her to go back to school for a master’s in counseling at the Seminary of the Southwest. She also began collaborating with a physician at Dell’s Children, Dr. Rahel Berhane, in research about healthcare for families of children with complex illnesses.

“At the time there was little information about service utilization and cost for this population. Dell Children gave us seed money to investigate this issue, and see if a comprehensive care clinic could lower cost and make a positive impact on families’ wellbeing.”

In 2012, this research collaboration resulted in funding from Seton Healthcare to open the Seton Children’s Comprehensive Care Clinic in Austin. At the clinic, families like Koch’s receive wraparound care: comprehensive care for the child with the complex condition plus coordination with the many service providers and supports for family members and caregivers.

“That was my first experience with grant writing and research, and I felt it was a gift from God,” Koch said.

That same year, Koch was accepted into the Steve Hicks School of Social Work’s doctoral program. She found her academic home at the school’s Institute for Collaborative Health Research and Practice, of which she was a fellow.

“I initially thought I was going to do direct service support, emotional support. But then I realized that changing systems was really compelling to me, and that I seemed to be good at doing research and writing grant proposals. I think that if I can make a difference at the systems level, that’s where I am best used.”

Changing systems

On a sunny morning last August, Koch was at the Austin’s Ronald McDonald’s House decoding a web-like diagram of multicolored ovals connected by lines and arrows for a small group of nurses, social workers and case managers.

Known as “Gabe’s Care Map” and drawn by Gabe’s mother, the diagram captures what it takes to raise a kid with complex care needs — in Gabe’s case, a rare genetic disorder called Noonan syndrome. The map has blue ovals for health care providers, purple ones for assessment services, red for school-related personnel, turquoise for advocacy groups, pink for recreation opportunities, orange for anything related to legal and financial matters, and green for sources of support. The lines to some of the ovals are intercepted by small door icons, which represent barriers. Smacked at the center, a circle marked with a capital “G” stands for Gabe and his family.

Koch explained to the group that since Gabe’s mother published the diagram in her blog in 2011, “care mapping” has become a useful tool in the healthcare field. The maps literally put the patient and the family at the center, and help all service providers understand the complex web of which they are only a tiny part.

This was day one of a professional workshop (funded by the Texas Department of State Health Services) that Koch and her team are delivering throughout the state to help providers better understand the needs of youth with complex health conditions, particularly as they age out of pediatric care — as Caelan did.

In most of these cases, Koch explained, youth and their families struggle to find providers of adult healthcare with enough knowledge about neurological and other disorders primarily associated with pediatric patients. And if they find them, there are still obstacles ranging from effective inter-professional communication to insurance policies that trigger at age 18.

“As a nation, we had tried to promote effective transition from pediatric to adult primary care for children with special healthcare needs for about 30 years. There is great work done by an organization called Got Transition, but we still have a long way to go,” Koch said.

During the doctoral program, Koch had conducted research that revealed that the great majority of nurses, medical residents, and social workers in hospital settings didn’t know enough about the challenges of transition for this specific population. She developed the workshop to address this gap, and is now re-packaging the information into a research project template about transition that medical students and residents can choose to conduct to fulfill their degree requirements.

“The medical curriculum is pretty full and students have very limited amount of time. But the organization that accredits medical schools and residency programs requires students to conduct a research or quality-improvement project. My goal is to offer this material as a doable option for them so that they leave medical school with knowledge about the challenges of transitions for children with complex needs and their families,” Koch explained.

Looking back at the beginning of the journey that started with Calean’s birth, Koch said she is sometimes surprised about how things turned out.

“It took me a while but I found out that I am best at bringing everyone to the table, gather the data, look at the metrics, figure out the best way to put all that into a proposal and then execute and evaluate it,” she said. “And it’s joyous for me. I love to look at and change systems, and I didn’t expect that. I was getting my master’s to work with people, and now I have a doctorate to work for people.”

–

By Andrea Campetella. Photos provided by Kendra Koch.