Military spouses tell their stories

Things started to fall apart for Anne Jackson in 2008, when her husband MJ was deployed to Afghanistan in support of Operation Enduring Freedom.

It seemed like ages since they had met at the Midnight Rodeo, a honky-tonk in Lubbock, Texas. Jackson was then finishing her law degree at Baylor and MJ was a pilot in training at Reese Air Force base who surprised her with his two-stepping skills. Five years later, he surprised her again when he proposed over the PA system at the football game during Jackson’s 10-year high-school reunion in her hometown of Gruver.

The newlyweds moved to Fort Hood, and then to Dyess Air Force Base in Abilene, where Jackson first experienced the hardship of separation. Only a few weeks after their second son was born in January 2002, MJ was deployed to Iraq. Although it was an arduous four months apart, Jackson was not working outside of the home at the time and was able to move in temporarily with her parents for support.

Things were very different in 2008. Jackson, who had re-started her law career after their third child was born, was then assistant county attorney for Bell County. With MJ away, she had to juggle a demanding job, the full responsibility of raising three young children, and the constant worry about her husband being in harm’s way. The relentless pressure, Jackson says, turned her into a very angry person.

“You are always scared, but you have to take care of business, and you have to act tough. So when things don’t go well, when the kids get into trouble at school or the water heater breaks or the dog dies, you become angry to take care of business. If you can yell, and get the job done, then you can move on,” she said.

The separation from MJ was also difficult on their children. One day their middle son came home from school and asked Jackson whether “the guys in the hallway pictures were still alive.” Jackson, who had recently given a portrait of MJ to the school, felt her heart sink as she realized that in her son’s experience, formal portraits always depict deceased people and that he had spent the day wondering if his dad was dead and nobody had told him.

“People would tell you, kids should not have to deal with adult problems. But when their father is putting on a helmet and a bulletproof vest and going to Afghanistan, saying that he is going to fight bad guys is not enough. You have to be somewhat honest and tell them, this is what war is,” Jackson said.

Upon MJ’s return from this second deployment, things only got worse. He was detached and easily angered, which put the whole family on edge. Jackson, who had been waiting for MJ’s return to get some respite and resume family life, felt deeply frustrated. One day, as they were standing in the kitchen, MJ hesitantly

shared that he was not sure what was wrong but that he felt overwhelmed.

“And I was like, you feel overwhelmed? You were by yourself doing your job for six months while I was home doing my job, working full time, with three kids. I have been waiting for you to come home and be a dad, I don’t care if you are overwhelmed,” Jackson told MJ.

In retrospect, she knows that this was probably not the best thing to say to a returning warrior, but that was reality for her at the time. It was a breaking point, and she realized that they needed help.

Jackson knew marriage counseling was not an option for MJ — he was a major trying to be promoted to Lt. Colonel.

“There is this perception that if you are breaking mentally in some way, that does not speak well of your ability to be a commander. You are supposed to be a warrior, to be impenetrable, a man of steel. My own impression is that if you can talk about it and get better, you will be an even stronger leader because your men are going to experience that at some point. I think the military is coming around to this idea,” she explained.

Jackson had seen advertisements for Military OneSource — a 24/7, one-stop shop for services — and one day she decided to call. “I think I need help, but I don’t want the military to know about it,” she told the person who answered the phone. They put her in contact with a counselor, whom she started seeing during her lunch hour, without anyone in her family knowing.

“I went there, and I started crying. And I still see her, almost eight years later. She understood my problems, she helped me get the autism diagnosis for my older son. In 2012 when MJ was so depressed that he was shaking and could not function, I snuck him through the back door of her office, at Christmas. She started seeing him informally, and when he got closer to retirement in 2014, he realized he could let go and talk about what was going on.”

***

Jackson shared her struggles with military family life on a Saturday morning in the summer of 2017, during a meeting of the Veteran Spouse Network.

The brainchild of Elisa Borah, a research associate professor at the Steve Hicks School of Social Work, the Veteran Spouse Network creates connections among spouses of veterans across Texas, and between spouses and researchers like Borah, who seek to help military families.

Borah knows too well the toll that fifteen years of continuous war has taken on soldiers. She spent four years managing clinical trials for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among active duty military personnel at Fort Hood, in one of the busiest Department of Defense’s research sites in the country.

But, in true social work manner, she also knows that soldiers’ challenges are their families’ challenges, whether it’s learning to live with a severe injury, coping with mental health issues, adjusting to civilian life, or facing unemployment. In 2015, Borah joined UT Austin with the goal of better understanding and serving the needs of veteran families, especially spouses.

“It is often spouses who encourage the veteran to seek treatment in order to save their marriage or improve family relations. They are vital to veterans’ successful transition into civilian life. They also become the family’s breadwinner when veterans are unable to work,” Borah explained.

Borah believes that the entire family serves when military personnel serve. Recent research suggests that deployments, in fact, not only take a toll on soldiers’ mental health but on spouses’ mental health as well. A 2017 New England Journal of Medicine study, which analyzed medical records of more than 250,000 spouses of active duty soldiers between 2003 and 2006, found that multiple and prolonged deployments typical in Iraq and Afghanistan were associated with more mental health diagnoses for depressive, anxiety, sleep, acute stress reaction and adjustment disorders. The article lists many of the challenges that brought Jackson to the breaking point: maintaining a household, coping as a single parent and experiencing marital strain due to deployment-induced separation and difficult reintegration.

Despite spouses’ vital role and risks to their mental health, there is not enough support for them. Borah wants to change that.

“I was doing focus groups with Texas veterans, and the spouses came because they had volunteered to help. And they told me, ‘This is great, we want to support our veterans, but there is nothing for us.’ I’ve heard this message so strongly across the state that I created the Veteran Spouse Network to help fill that gap,” Borah said.

Through state chapters and an active online presence, the network serves as a clearinghouse of information for veteran spouses seeking support, services and connecting to others who are going through similar struggles. It also allows researchers like Borah to obtain direct input from the population they want to help.

Through state chapters and an active online presence, the network serves as a clearinghouse of information for veteran spouses seeking support, services and connecting to others who are going through similar struggles. It also allows researchers like Borah to obtain direct input from the population they want to help.

On the Saturday morning that Jackson joined the network’s meeting, a small number of spouses — all women — and researchers were kick-starting the development of a curriculum for peer-support groups. Men are welcome to the group but Borah said they have been more difficult to recruit.

In one of the opening activities, the group’s facilitator that day asked the women to write traits of military spouses on post-it notes. Once the colorful notes were posted randomly on a wall, words like ”frustrated,” “on edge” and “tired” but also “resourceful,” “willing” and “strong” expressed the simultaneous strain and resilience present in every spouse. Both qualities, as well as a deep commitment to help others, also showed in the stories that the women shared that day.

There was for example Melissa, a Winsboro veteran county service officer and cattle rancher with a deliberate manner, who is also the wife of a disabled Vietnam veteran who struggled with PTSD for many years before he was diagnosed.

“When he was diagnosed with PTSD I was relieved. I instantly went back 20 years, and many things made sense. We had come out with our own words to describe what happened. His nightmares, we called them jungle dreams. And I learned very quickly not to wake him up from them: you get out of the bed, go to the end, wiggle a toe, and say, hey, you are having a bad dream, wake up. That’s what I learned to do to survive,” she shared.

Melissa now uses her own experience with her husband’s PTSD symptoms with the veterans and spouses that visit her Winsboro office to find help in accessing services.

There was Nelida, an outspoken medical consultant, active grassroots organizer and the main caregiver of her veteran husband. He struggles with PTSD, traumatic brain injury, physical injuries, and a few years ago, at age 35, went into heart failure. Nelida also serves at the Veteran Spouse Network’s representative in El Paso.

“I found that networking and being connected with nonprofit organizations across the country has helped my family thrive, pay the bills, get to Houston when it’s been an emergency … I go to every VFW [Veterans of Foreign Wars] meeting, town hall meeting, anything, and let them know that we the caregivers and the spouses and the families matter. It’s because of me that my family is thriving, if it was up to my husband he would never ask,” she said as other members nodded in agreement.

There was also Irene, a retired computer trainer who met her husband Bill after his Vietnam service while both were volunteering at the Addison Community Theater— now Water Tower Theatre. Bill has Agent Orange lung cancer from Vietnam. Irene said that she is always on the alert for triggers that can put her husband on edge.

“After the Vietnam War they called it an emotional death. Warriors get withdrawn, cut off from the world, and then heal and come back out until something triggers it again. It’s a roller coaster for the spouses, and I can’t imagine having to deal with that and also having kids or a full-time job,” Irene shared with empathy for the other spouses in the room.

During a phone conversation, Irene said that she has encouraged her husband to write and publish Vietnam-related poetry as a way of processing his trauma. They are also the creators of “the 191,” a website dedicated to members of the 191st Assault Helicopter Company in Vietnam, in which Bill served as a pilot.

“You know, the men of the 191 all had good jobs, good families, you see them and say, they are perfectly healthy. But you get the women together and talking, and we all experience these episodes, and we all are trying to put them back together every time they sink down or get depressed or get aggravated. Being involved with the 191 was really a learning experience for me,” she said.

And there was Jackson, who told the group about how she started to see parallels between the tension in her home after MJ’s return and the family violence cases she was prosecuting in Bell County.

“I started seeing these dynamics after 9/11 where there was family violence right after soldiers got back from a deployment. What looked like typical family violence was actually untreated combat reunion and reintegration issues. I started reading books to figure out what was going on, and worked to get services to soldiers with undiagnosed and untreated mental health challenges, instead of just criminalizing their behavior,” she explained.

In 2015, Bell County formed its own Veterans Treatment Court, which serves veterans charged with a misdemeanor offense whose military or combat-related experiences contributed to the commission of the offense. The court relies on certified veteran peer mentors who assist participants through the court process, and provide support, encouragement and help in navigating services.

“I was able to get my husband to volunteer for it, so now he is a certified peer mentor for the veterans court. He has gone from thinking that mental health and talking about your problems was a joke to doing it every day with veterans,” Jackso said to the rest of the group’s cheers.

After a few more meetings during the fall of 2017, the 12-session curriculum was finished and ready to be piloted in spring 2018. The next goal, Borah said, is to train members of the Veteran Spouse Network to serve as peer co-facilitators of support groups throughout the network’s regional chapters. Borah also plans to evaluate the curriculum with pre- and post-assessments to learn how to further improve it.

In the meantime, the network is already having a positive impact on the spouses who have joined it during this initial phase.

“I’ve always wanted the rest of the country to understand how hard this is,” Jackson said. “We have been deploying for 16 years. We military families don’t

just need your support when our guys are gone. We need it when they are back too. And it’s not all parades and rainbows and YouTube clips where everybody is crying because they are so happy. It’s a lot of hard work.”

Jackson paused for a moment and then added, “In the middle of all this, being able to talk to people who also lived this life and went through what I went through … that provides a lot of healing. It reminds you that you are not crazy, that you are not alone.”

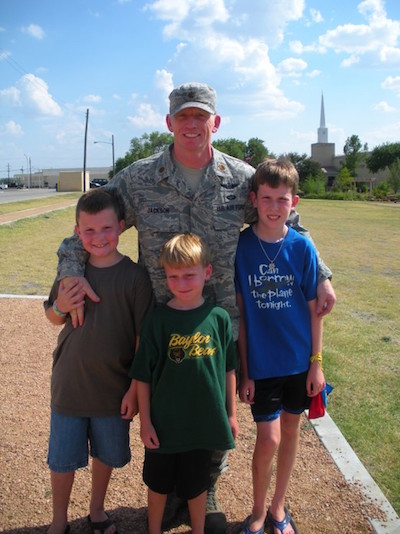

Written by Andrea Campetella. Photos provided by Anne Jackson and Irene Janes.