We all have seen it on CSI, the popular Crime Scene Investigation TV drama: Forensic evidence is collected and sent to a lab, a key piece of information is found through DNA results, and the case is miraculously solved, all within an hour’s time, including commercials.

“The reality of crime investigation is in fact much more complex than forensic testing, particularly when it comes to sexual assault crimes,” says social work professor Noël Busch-Armendariz, who directs the Institute on Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault (IDVSA).

“DNA does help us identify the offender, but in many sexual assault crimes that’s not enough, because the case may pivot around issues of consensual versus non consensual sexual contact. Unfortunately, DNA technology cannot give answers to these complex questions.”

For the past three years, Busch-Armendariz and the IDVSA research team have experienced up close the complexity of investigating sexual assault crimes, through leading an action research project with the Houston Police Department (HPD). As the project reaches its final year in 2014, it has produced remarkable changes in the way HPD investigates sexual assault crimes, and the Houston professional community responds to them. (Watch this video about the project).

At the heart of these changes is IDVSA’s main contribution: an approach that empowers victims by giving them resources and a voice in the crime investigation process.

The initial problem: Untested forensic evidence

A Sexual Assault Kit, or SAK, is a box containing instructions and materials to collect relevant biological evidence–such as hair and vaginal or anal fluids–from a sexual assault survivor. The victim’s body becomes, in fact, the crime scene. Specialized nurses called Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANE) collect the evidence if the victim makes the decision of going through this tough process.

“SAKs contain very pe rsonal evidence,” explains Caitlin Sulley, IDVSA research project director. “And let’s remember that this evidence is collected after a traumatic event and through procedures that are quite invasive. Survivors submit to these procedures because they hope that the evidence will hold the perpetrator accountable, and prevent others from experiencing a similar assault.”

rsonal evidence,” explains Caitlin Sulley, IDVSA research project director. “And let’s remember that this evidence is collected after a traumatic event and through procedures that are quite invasive. Survivors submit to these procedures because they hope that the evidence will hold the perpetrator accountable, and prevent others from experiencing a similar assault.”

Research sponsored by the National Institute of Justice, however, found that the response system was failing survivors of sexual assault crimes. A 2007 report showed that SAKs were sitting in police property rooms across the United States, untested—that is, never submitted to a crime lab.

“Depending on the extent of injuries and types of evidence to be collected, the examination by a SANE nurse may take anywhere from two to twelve hours. What will survivors’ perceptions of the response system be if nothing happens with this evidence taken from their own bodies?” Sulley asks.

In 2011, Busch-Armendariz with colleagues from Sam Houston State University and the Houston Police Department received funding for an action research project to address the issue of untested SAKs in Houston. After an initial assessment, HPD had determined that its property room held more than 6,600 untested kits. Some of the kits had been sitting there for more than two decades.

The approach: Action research

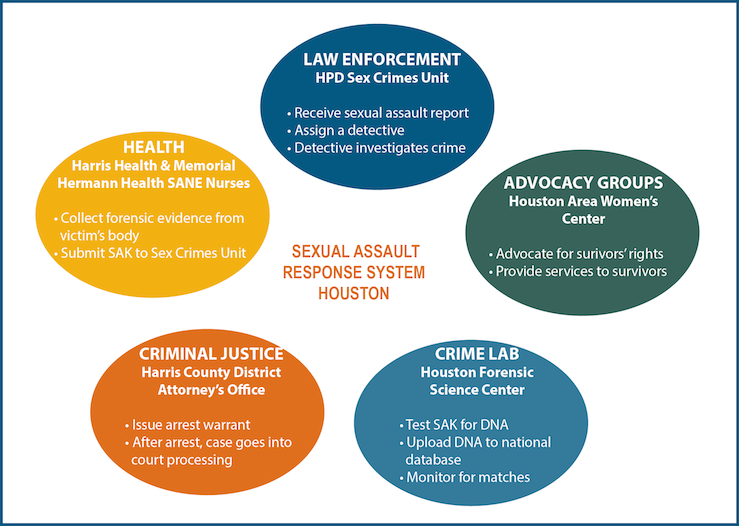

In an action research project, researchers work together with all stakeholders to understand the issue at hand, develop and implement strategies to produce change, and evaluate the results. The complexity of sexual assault is reflected in the number of stakeholders that respond to this type of crime.

These stakeholders joined IDVSA and Sam Houston researchers in 2011 to understand why SAKs had not been tested, devise strategies to prevent this from happening in the future, decide how to prioritize testing of SAKs that had been sitting in HPD property room, and develop strategies for the notification and re-engagement of victims.

“An honest conversation for problem-solving rather than blaming was at the heart of this collaboration,” Busch-Armendariz says. “Each stakeholder illuminated different pieces of a SAK’s complex, and many times truncated, journey from collection of evidence to use of that evidence by the criminal justice system.”

IDVSA researchers’ specific task was to give voice to victims, identify their needs in the investigation process, and determine the best way and timing for the response system to re-contact them if tested SAKs generated a match in CODIS, a national database that contains DNA samples from convicted offenders of any kind.

The process: An upward learning spiral

As the working group began to meet regularly, its members had a productive conversation about sexual assault that was transformative for all the parties involved.

“It has been an iterative learning process, which is a main strength of action research,” Sulley says. “It’s about what we learn from each other as we, as a multidisciplinary group, think and work through an issue as complex as sexual assault. “

One result of these conversations was a better coordination and integration of the multiple systems that touch a survivor’s life. For instance, as the group shared information about kit testing, SANE nurses learned from crime personnel that they should put the first possible sperm evidence on a swab, instead of on the glass slide that came with the SAK.

The working group also adapted to unexpected policy changes. In September 2011, Texas Senate Bill 1636 directed that all kits be submitted for testing within thirty days of collection.

“We had learned early on that practices had changed over time in Houston,” Sulley says. “Sending a SAK for testing was at times mandatory within HPD, but at other times the detectives in charge of the cases made the decision. And they might decide not to send a kit for testing because the identity of the offender was already known, or because they didn’t think the victim was credible enough to make the case go forward.”

At this the same time, the City of Houston decided to test all kits in their inventory. With the room for discretionary testing eliminated, the working group redirected all its efforts towards how to re-engage survivors and better serve them.

“While the senate bill and the decision of the city of Houston were important in many ways, testing results do not give us all the answers,” Busch-Armendariz explains. “Each SAK belongs to a victim, and we had questions about them: did they want to be notified about test results? If so, how? What kind of support did they need? What was the impact for survivors of re-engaging with the criminal justice process, in many cases years after they reported the crime to law enforcement?”

To answer these questions, IDVSA researchers conducted interviews with survivors and the professionals who serve them. Although recommendations varied, a consensus emerged around survivors’ right to have a choice and be able to exercise a degree of control in the notification process. With this information, the working group devised possible responses, which HPD then implemented into procedures.

For the last phase of the project, IDVSA researchers are evaluating these procedures. They are conducting interviews with survivors re-contacted by HPD after test results of their kits produced a DNA match that might result in an arrest.

The results: A paradigmatic shift

The long-term result of the action research project has been a paradigmatic shift in all response system agencies, with a renewed focus on survivors’ needs.

The paradigmatic shift is manifested in some of the new strategies that the Houston Police Department has implemented, such as the creation of a justice advocate position within the adult sex crimes unit. The advocate is a social worker that assists victims directly, provides crisis intervention, offers information about community resources, and serves as the liaison between the victim and the detective in charge of the case. HPD has also created a sexual assault information phone line and email account that victims can contact at any time.

“The Houston Police Department showed great leadership in this regard,” Sulley says. “They reached out to other police departments throughout the country to learn how they were addressing sexual assault and what kind of services they were providing to victims.”

“I think the consensus is that HPD will be considered a model for addressing the issue of untested SAKs,” Sulley adds. “I say a model, and not the model, because certain strategies that are good for Houston might not be feasible for other jurisdictions.”

This paradigmatic shift is already having an impact on survivors’ lives.

“In one of my recent interviews, a survivor told me that she has seen incredible change in HPD from her initial report years ago and the way they reached out to her now,” Sulley says. “The fact that they treated her with dignity and respect, and that she was able to have a voice in the criminal justice process made her realize that change was possible in her own life.”

“The shift of focus from SAKs and forensic testing to a more holistic discussion about sexual assault crimes and victim-centered responses has improved both investigations and outcomes for victims,” Busch-Armendariz concludes. “This is a way forward towards a broader cultural shift about how we view sexual assault crimes in our society.”

| By Andrea Campetella