By Montinique Monroe | Texas Steve Hicks

In May, a few weeks before George Floyd’s killing shook the nation, I was the only journalist to attend Michael Ramos’ gravesite ceremony in Austin.

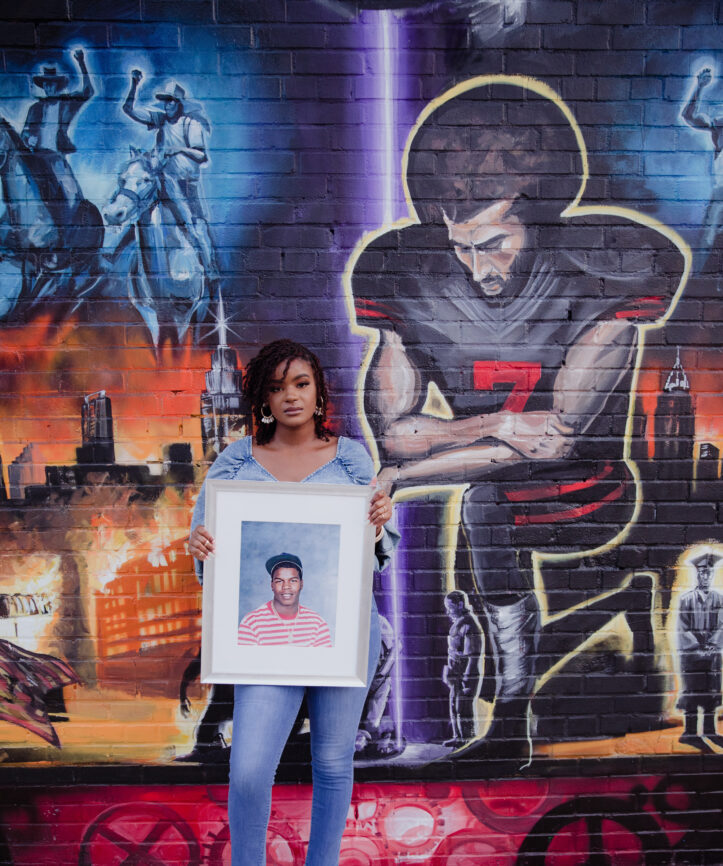

Ramos, who was Black and Hispanic, was shot by police officer Christopher Taylor on April 24. Officers, who were responding to a 911 call about people allegedly doing drugs in a car, said Ramos wouldn’t comply with their demands. They first fired a non-lethal bean bag round at him, and when Ramos got back to his car to drive away, Taylor shot him. Michael, who was unarmed, died in the hospital hours later.

When I received the notification that Ramos had died, I knew I needed to reach out to his family not only to bring light to his story but most importantly to share my condolences. I began communicating with his mother, Brenda Ramos, and was invited to photograph his ceremony at Assumption Cemetery on May 15.

I experienced many emotions as I entered the cemetery that day. I not only had to mentally prepare myself for the grief I was about to witness but I also had to determine how, as an outsider, I would do my part to document this grieving family with as much compassion as possible. Capturing pain and vulnerability after a crisis is something I do not take lightly.

After weaving in between graveled pathways among hundreds of graves, I finally arrived at the space dedicated to Michael. I sat in my car for a few minutes watching his family and friends gather around a display in his honor – a colorful flower arrangement shaped as a cross next to an easel with a portrait of him. I took a deep breath, bowed my head, said a prayer and glanced out of my car window one more time before exiting. I’d never met Brenda in person, yet my eyes immediately landed on her. She was busy setting up for the ceremony and greeting friends and family when she could.

I gained enough strength to get out of my car and quietly made my way into a short line of people waiting to greet Brenda. When I made it to the front of the line, I handed her a sympathy card, introduced myself and reminded her of what we had in common. She’d lost her son to police violence as I’d lost my father, Paul Monroe, who was killed by former Austin police officer Steven Deaton when I was only an infant. Tears filled our eyes. In the middle of the cemetery, in the midst of a global pandemic, we embraced.

As the ceremony began, I faded to the background as I usually do when I’m on a photo assignment, as if I wasn’t there. I needed to capture Ramos’ family in the purest most authentic way. I attempted to completely remove my emotions and maintain my role solely as a photojournalist.

But I couldn’t.

I watched through my camera lens, with tears, as Ramos’ best friend Gil Ortiz held Brenda during a prayer of comfort. As I looked at Brenda, I saw my Granny and how she must have felt when she buried my father.

When I learned about how my father was killed, I made it my mission to tell his story and bring light to untold and underreported stories like his. For the past five years, I’ve dedicated my free time as a photojournalist to families of victims of police brutality in Austin. I’ve yet to photograph many of them but I have grown to know them through interviews that turned into daily conversations about the pain and emptiness we share.

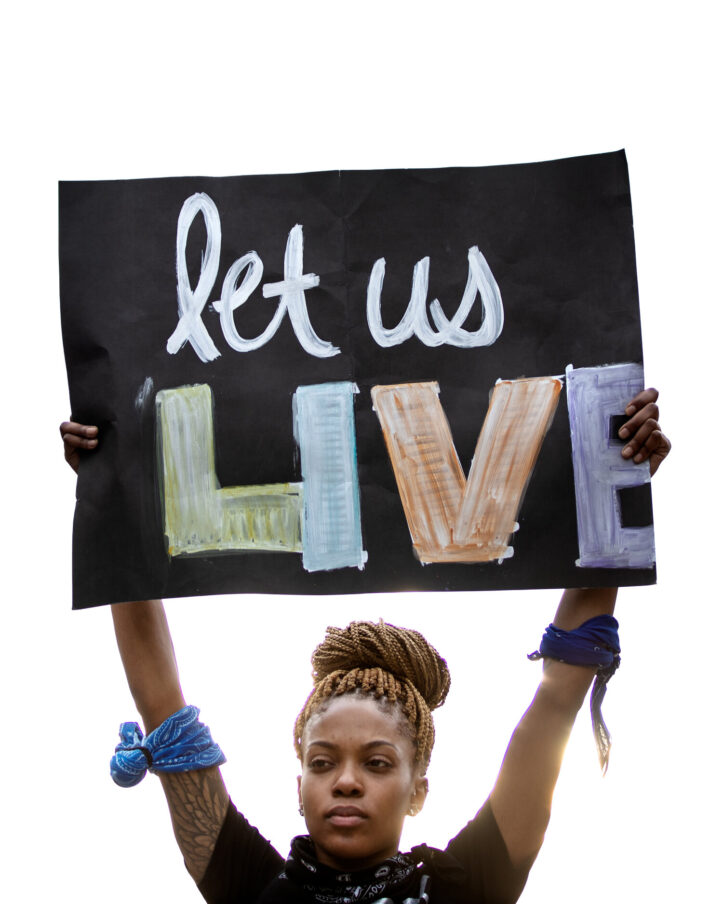

In May, when protests against police brutality spread across the country and in my hometown, the place my father was killed, I knew I needed to be present. My perspective was important. I chose to go out and document because I felt it was my obligation, not only as a Black female photojournalist, but also as the daughter of a man who was killed by a police officer.

I began documenting protests a little after 11 p.m. on May 29, the first night of protests in Austin. Tensions were already high following Ramos’ death. Nation-wide anger sparked by Floyd’s death, led a local community activist to call people to gather in front of Austin Police headquarters. Floyd’s death along with the police killing of Breonna Taylor were the most recent examples of the humanitarian crisis that has always existed in the United States – wrongful killings of Black people at the hands of law enforcement. His death captured the attention of many in ways other police killings hadn’t, sparking civil unrest. But this unfortunate reality is all-too familiar to people in my community, many of which were present that night in Austin.

I watched as officers stood firm in their human-made wall in front of the headquarters building. People cried out the pain and frustration they’d held in for so long. I witnessed raw anger on both sides. I met family members of victims of police brutality I’d never met before. They were tired of seeing dead Black bodies in American streets. We were all tired.

Two days later, on May 31, during another demonstration a group of people began marching peacefully from the Capitol toward I-35. As they approached the highway, officers used tear gas to try to disperse them. Unsuccessful, the officers allowed them to occupy the highway for about 30 minutes. After exiting, demonstrators arrived at the Austin Police headquarters, where they chanted and made statements before being met with more tear gas and rubber bullets.

I’d never seen Austin show up for Black lives like this. There were moments where I’d put my camera down and just simply exist among the demonstrators. Tears would fill my eyes and I’d find myself chanting along with them through my mask. These were people who took time out of their daily lives to do what they believed needed to be done in honor of people like my father, who can no longer speak for himself.

History has taught me that disruption provokes change. Although nothing will bring back my father or any of the lives taken by law enforcement, I hope people continue to fill the streets, speak out and refuse to be comfortable in the face of racism. As we continue to witness civic unrest across the nation, I hope we never forget the people impacted and taken from us, right here in Austin.

Michael Ramos, ‘20

Javier Ambler II, ‘19

Isaiah Hutchinson, ‘19

Aquantis Griffin, ‘18

Morgan Rankins, ‘17

Landon Nobles, ‘17

Lawrence “Pickle” Parrish, ‘17 (survived)

David Joseph, ‘16

Larry Eugene Jackson, ‘13

Ahmede Jabbar Bradley, ‘12

Byron Elliot Carter Jr., ‘11

Roger Tyrone James, ‘09

Kevin Alexander Brown, ‘07

Malcolm Thomas Smith, ‘07

Jessie Lee Owens, ‘03

Sophia King, ‘02

John “Johnny” Paul Cornell, ‘99

Stacey L. Conner, ‘97

Rickey Lee Wolfe, ‘94

Paul Anthony Monroe, ’93

James “Jimmy” Earl Moore, ‘91

… and countless others.

Posted by Montinique Monroe on September 17, 2020. Monroe is the digital content creator for the Steve Hicks School of Social Work.