King Davis’ quest to preserve the records of the Central Lunatic Asylum for Colored Insane in the digital age

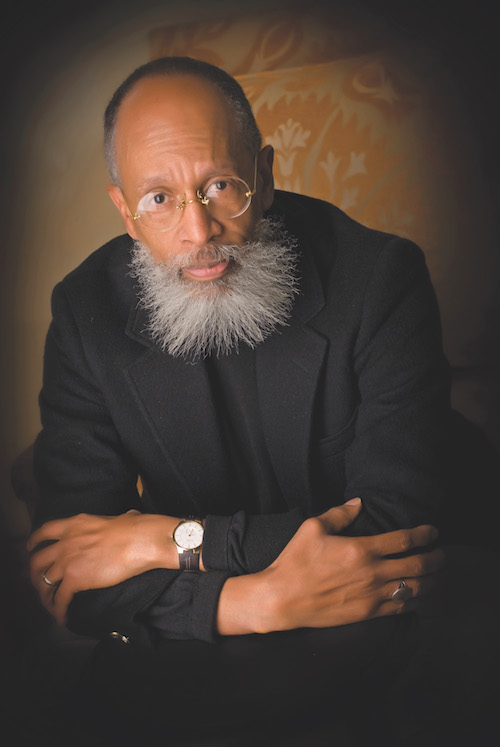

By Andrea Campetella. Photos provided by King Davis.

In January 1990, as the new commissioner of mental health, substance abuse, and developmental services for Virginia, King Davis had to defend his proposed budget before the state’s senate and house finance committees. The one question he was not prepared to answer was why the budget requested funds to store thousands of psychiatric records, some dating back many decades. One senator suggested saving money by simply destroying the records; he argued that they had no utility or value and that destruction would also guarantee patients’ privacy.

Fast-forward to 2019, which marks the 10th anniversary of the Central State Hospital Digital Library and Archives Project. Led by Davis and a team of 17 scholars, this project located, restored, cataloged, and digitized hundreds of thousands of records (photographs, admission records, annual reports, board minutes, and more) from Virginia’s Central Lunatic Asylum for Colored Insane. The asylum, later re-named Central State Hospital, was founded in 1870 as the first psychiatric institution in the United States exclusively for people newly freed from slavery.

The Archives Project fully justifies that 1990 budget line. The resulting collection constitutes the most complete records of public mental health admissions of black populations in American history.

Thanks to this labor of love, African American families are finding information about relatives lost to psychiatric institutionalization; scholars from all over the world are mining the records to shed light on how race-based assumptions informed mental health theories, practices, and policies; and the interdisciplinary team led by Davis has accumulated an unparalleled level of expertise on the ethical, legal, and technical issues around privacy, preservation, digitization, and access to sensitive health records.

The Utopian spoke with Davis about this project and its significance for the present. The interview has been edited for clarity and conciseness.

How did this project start?

About ten years ago, I received a call from the director of the Central State Hospital, which is located in Petersburg, Virginia. He wanted my advice because he’d discovered that the hospital had lots of records going back to the 19th century, and that they were in jeopardy on two fronts. They were in a non-archival environment, that is, places in the hospital where summer temperatures would exceed 112 degrees, and where many different people handled or had access to them. And he’d been advised that Virginia law required the hospital to destroy all records older than ten years. The director asked if I was aware of the Virginia Retention Act and if I could help them preserve the records.

I was very concerned because this was one of the 17 hospitals that I managed when I was commissioner, back in the 1990s. And I knew about this hospital’s history. It was the only mental institution for African Americans in the state until integration was federally forced in 1968. What I didn’t know was that they had preserved practically every piece of paper since about 1868.

What are the goals of the project?

In the first six years, we focused on locating, restoring, cataloging and digitizing 800,000 paper documents and 36,000 photographs, slides, and negatives maintained in the hospital.

As the project advanced, in addition to preserving and increasing electronic access to these documents, we analyzed state and federal laws on access, privacy, and confidentiality of mental health records; we developed a model for storing and making digital mental health records accessible in ways that are ethical and maintain privacy as required by federal and state laws; and we created a dark archive and digital library (coloredinsaneasylums.org) that serves as proof that this model is viable.

But we didn’t anticipate how significant the content of the records would become.

Tell us about the records’significance.

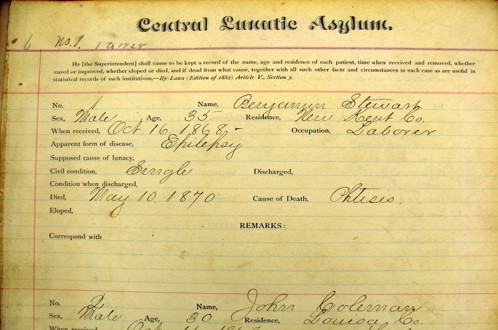

The hospital had thousands of their original documents and photographs from 100 years of segregated admissions and treatment. The first thing that struck me was the admission records. For every person that was admitted to the hospital, there was an index file that shows the name, city of residence, occupation, age, diagnosis, when the symptoms started, and the cause of their condition. I had never seen records like these in my years in mental health, where every person had an identified cause of their illness.

And what struck me the most was that in many instances the cause of their mental illness was freedom; the inability of black people to manage freedom. I was confounded. That is what really got me going: looking at the reasons why people were committed to the hospital and understanding more about the history of segregated mental health in Virginia.

Our content analysis of the documents also suggests a relationship to the long-term disparities that the black population in this country has experienced when it comes to mental health access, diagnosis, and treatment.

What are these disparities and how does this project help us understand them?

Contemporary meta-analyses show that African Americans, particularly male, are over-represented in diagnoses of severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia. These studies raise important questions about how psychiatrists are trained, about the implicit biases that may affect the accuracy of diagnoses. [See how social work researchers are trying to address this problem].

And now our project brings a sobering historical perspective to this issue. We are in the process of collecting and analyzing data on admissions of African Americans to Virginia’s mental health hospitals from 1840, when free blacks were given permission to access the one mental health institution in the state, to 1940, when federal and Virginia privacy laws allow us to access these health records for research purposes.

We have approximately 30,000 individuals in the database. We found that about 75 % of the diagnoses are severe mental illnesses like psychosis and schizophrenia. 75 %! Proportionally, this is larger by far than any population in the world.

So the over-proportion of African Americans diagnosed with severe mental illness in the historical data, 1840 to 1940, is replicated in the contemporary meta-analyses. This is frightening.

Given this over-proportion, the chances are very good that many of these diagnoses are invalid. And we have a way to find out, because the Central State Hospital kept about 5 million pages of treatment records all the way back to 1858. Going forward, we would like to select a sample of maybe 3,000 individuals and have a team of ten psychiatrists do a blind review and re-diagnosis.

What do you hope this project accomplishes?

The records we have helped to preserve and make accessible tell us so much about the past. We hope they also help us understand the nature of the future we want. We must learn from these materials to avoid repeating the same errors—inappropriate diagnoses, the pulling of people away from their communities and into an institution, perhaps for the rest of their lives.

We must recognize how important this information is, and make it a part of the curricula in programs of social work, psychology, nursing, psychiatry, and medicine. In all the helping professions, we need to be much better at recognizing our biases, and recognizing the social determinants of health so that hospitalization occurs only when necessary and appropriate.

What has been your most rewarding experience over these ten years of the project?

Connecting people to family members who were in the hospital has been most rewarding for me. I get calls, emails, and letters asking if I know of a person who was hospitalized there. Not long ago, a woman who was born in the hospital—her mother had gotten pregnant sometime after she was hospitalized—called me because she was trying to find her twin brother She had been adopted by her mother’s aunt and uncle, but nobody seemed to know what happened to her twin brother. I do genealogical workshops all over Virginia, trying to help individuals trace their family members to the hospital and learn what happened to them.

I can’t do much with digitization and the technological aspects of our project; I don’t know Fedora or Zooniverse or the other systems our team is using. But I can definitely get into the data on the 30,000 admissions. I can pay attention to the persons, to where people come from, their diagnosis, and the reconnection to families. In addition, I want to use our data to change policy, practice, and education. That’s what I love to do.