Do video statements help prosecute domestic violence cases?

Leila Wood still remembers with detail one of the first video statements she saw of a victim of domestic abuse.

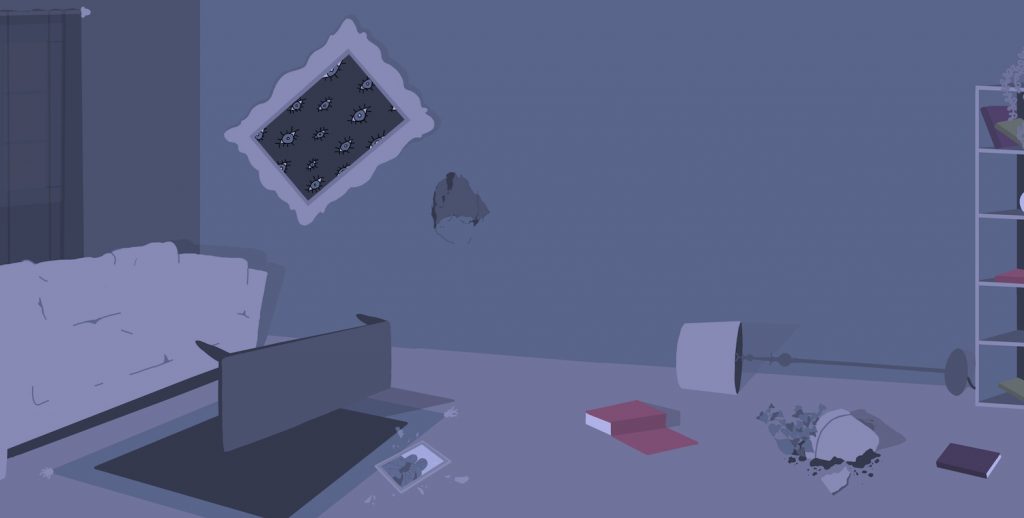

“I could hear a child crying in the background and seen things thrown around throughout the house. A woman was describing the assault and the camera closed up on her face, where you could see a black eye, and then she moved her hair apart and you could see an injury,” Wood said and paused for a moment. “And then, as the woman said, ‘and he threw me against the wall,’ the camera panned to show a body print on the wall, made from the impact. And that’s hard to forget,” she added.

Wood, a research assistant professor at the Steve Hicks School of Social Work, is leading an evaluation of the use of video statements in domestic violence cases in three Texas jurisdictions. The goals are to learn whether video statements affect case readiness for prosecutors, law enforcement officers’ experience, offenders’ accountability and victims’ experience with the criminal justice system.

THE ROAD TO VIDEO STATEMENTS

Prior to the women’s movement of the 1970s, the criminal justice system treated disputes between spouses as a private matter. If police responded to a call, the typical response was to separate the parties involved and to advise the aggressor to calm down and perhaps spend the night somewhere else.

Due to grassroots efforts and several landmark civil lawsuits against police departments that failed to protect victims of domestic violence, the justice system started to develop policies such as protective orders and mandatory arrests. By 1986 nearly half of all police departments in the United States had implemented mandatory pro-arrest policies.

Arrests, however, would be meaningless without prosecution. And domestic violence can be hard to prosecute.

“After an initial call to 911, many victims are unable or choose not to testify in court, and if they do, they may recant their statements and testify on behalf of their alleged abusers, for whatever reason,” Wood explained.

By their very nature, in fact, abusive relationships erode resources — such as social support and economic independence — that are essential for a victim to participate in the criminal justice process.

To jump this hurdle, in the 1990s prosecutors moved towards evidence-based and no-drop prosecution, which relies on evidence (anything from 911 calls to police reports and medical records) and does not require the victim’s cooperation. By 1996, 66 percent of prosecutors’ offices across the country had adopted this approach.

In the past few years, smaller and cheaper cameras have made it possible to add video statements to the evidence law enforcement officers collect. Video statements have the advantage of vividly capturing victims’ emotional and physical condition moments after the assault as well as any signs the assault may have left in its wake — furniture tipped over, broken items, blood.

The main utility of these statements is during the preparation of the case. Due to inability to cross-examine a video, they generally cannot be used in court.

VIDEO STATEMENTS IN TEXAS: THE JURY IS STILL OUT

In 2011, El Paso police department pioneered the use of hand-held video cameras to take statements from victims of domestic violence. In 2016, the model expanded to 16 Texas jurisdictions. In that year, Wood and her team at the Institute on Domestic Violence & Sexual Assault began conducting interviews and focus groups with police officers and prosecutors in three of the 16 jurisdictions.

Preliminary analysis show that, overall, law enforcement personnel had positive experiences. Officers said video statements allowed them to convey complex information and increased their credibility by providing documentation of their actions. Prosecutors could makea quick initial assessment of a case by viewing the video and could get a deeper understanding of the victim’s experience and threats to safety. Videos also provided leverage when negotiating with the defense team.

After analyzing outcomes from 6,491 closed family violence cases from one jurisdiction, Wood and her team found that cases with videos were less likely to be dismissed and more likely to result in a plea agreement. In the next phase of the evaluation, the team will add new sites to better understand the impact of video statements on case outcomes, and to better understand victims’ perspectives and how video statements impact their agency and safety.

Evidence-based prosecution, Wood explained, was meant to reduce victims’ burden — by removing the decision of prosecution from the victim to the state, abusers could not coerce or threaten their partners to drop charges. But this type of prosecution can also reduce victims’ agency.

“If they don’t want the case to move forward for whatever reason, they don’t get to make that decision,” Wood said. “Moreover, the defense attorney gets to see the video. And the only time videos can be used in court is to impeach the victim if they recant. So, a very important part of our research is to understand the victim’s experience with the process.”

By Andrea Campetella. Illustration by Renee Koite