Celebrating 90 years of social work

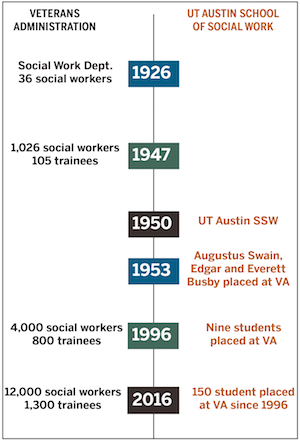

On June 16, 1926, General Order 351 established the social work program in what was then called the Veterans Bureau. Staff consisted of 36 social workers placed in psychiatric hospitals and regional offices throughout the country.

Fast-forward ninety years. In 2016, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, or VA, employs 12,000 social workers – it’s the single largest employer for the profession in the country. Every year, VA also trains more than 1,300 social work students through paid and unpaid internships.

We talked about this evolution with Laura Taylor, current national director of social work for the Veterans Health Administration. This September, Taylor will visit the Forty Acres to deliver the keynote address of the Annual Military Social Work Conference.

What made you join VA?

I actually started my VA career as a social work intern. I was surprised when my practicum director suggested VA, because I had accompanied family members to VA as a child but I had no idea that there were social workers there! When I did my internship, I knew that was it, it was like duck to water. I thought, this is what I was put on this earth to do, to serve veterans.

I come from a family of veterans. Both of my grandfathers were in WWII, and I was raised by a Marine who was severely injured in Vietnam at age 19 – he lost both hands and his eyesight as a result of combat – and who has never let that limit him in doing anything.

In the VA where I come from, there is a sign that hangs over main entrance, and I feel it sums up what VA means to me. The sign says, “The price of freedom is visible here.”

What are recent VA initiatives where social workers are involved?

Social workers are on the frontline of ending veteran homelessness. About 4,500 of the 12,000 VA social workers are serving homeless veterans. Since the inception of this initiative in 2010, these programs have rapidly rehoused, permanently rehoused or prevented homelessness for more than 230,000 veterans.

There has also been a phenomenal expansion of support for caregivers of veterans who are seriously injured in the line of duty on or after 9/11. Public law 111-63, under President Obama, allowed VA to provide services such as healthcare coverage, travel assistance to accompany veterans to their appointments, respite care benefits, monthly stipend to help offset their potential loss of income they have by rendering care, and mental health services. This program has helped more than 30,000 caregivers in the last five years. We get asked from other countries about it.

We are also working hard on breaking the cycle of intimate partner violence for veterans who experience it, use it, or are at risk of using it. We are establishing a clinical expert in each VA facility, screening, and partnering with community organizations to offer services. One of the promising practices we are excited about is Strength at Home, a psychosocial group treatment developed by Dr. Casey Taft. We have trained now clinicians in ten VA sites to deliver this program and have started running our first groups.

What should schools of social work do to prepare students to work with veterans?

What should schools of social work do to prepare students to work with veterans?

First thing is teaching about military culture. Also, train students in working with people who have experienced trauma. Finally, and this is not necessarily a social work competency, teach students to start from a place of yes. As social workers, it’s important that we look at possibilities and ask ourselves what can we do. I see entire social work departments obliterated because people spend their time telling clients no, we can’t do that. And VA is complex enough that you can find a policy to let you say no to literally everything. So it’s very important to star from a place of yes.

How can social workers in the community collaborate with VA?

We have developed an online military culture competency training (PDF) that I would encourage all non-VA clinicians to take (link). Also, when assessing clients, they should ask the question, “have you or a loved one served?” We have produced a pocket card of questions that anyone can ask to make sure they are identifying clients who have served (link).

It’s also important to have a basic understanding of VA services and benefits, so they can articulate why a client who served might want to consider visiting VA. Any agency can have a VA social worker come and give a presentation about services and benefits.

Finally, if they sit on an advisory committee or a task force, say on suicide prevention or sexual assault, I would recommend that they try to make sure that there is a VA person there, and if there isn’t, invite one to be at the table. Agencies can reach out to the social work chief or social work executive in their area VA, and they should be able to make those connections.

What are the challenges for the future?

We have grown much as a profession in VA, we have tripled our numbers in the last fifteen-twenty years. I don’t think this growth rate is sustainable, and the challenge moving forward is to justify our continued staffing level. When a medical center with a limited budget asks the question of whether hiring a social worker or another professional, we have to be able to show outcomes for our work and the difference we make – not only through good news stories but through data, metrics, and health outcomes.

This is also an opportunity for social work to shine. There is an increasing focus on the social determinants of health, nationally and globally. And there is evidence that when health care professionals work together, patients receive better quality care and better health outcomes. We social workers have been doing this kind of interprofessional collaboration for eons! And we are so good at being an interprofessional team player, that sometimes we don’t point the research back to us, and we don’t take the credit that we are due.