*This post may use some terms and vocabulary that some readers feel are out of date or inaccurate. We recognize the sensitivity of and inherent problems with referring to various indigenous peoples with monolithic and colonizer-imposed terms. For this post, we have made the decision to use the vocabulary of the sources from which information was pulled within its historical and cultural context.

This month, we’re celebrating Native American Heritage Month by highlighting library materials that celebrate Native American lives, accomplishments, and voices. For more information and additional resources, come visit our display on the third floor of PCL!

While this month’s designation has also been referred to under other variants of the name, including “National American Indian and Alaska Native Heritage Month,” the current designation reflects growing recognition of the continued presence of Native Peoples, far predating European exploration and colonization. The trend toward the term “Native American” also reflects the misnomer of the term “Indian” as European colonial explorers incorrectly assumed they had found a western passage to India/ East Asia. The term Native American was proposed by the U.S. government. This is an ongoing, evolving term in how Native Peoples identify and describe themselves, as well as how they are identified by others. As Native Peoples are far from being a monolithic identity, some identify as native, indigenous, Indian, First Nations, or specifically to their tribal identity(ies). This can be more complex for individuals with multiple heritage backgrounds.

Native Peoples have served as an inspiration throughout U.S. history, with colonial settlers appropriating aspects of tribal cultures dating from the first act of disobedience by New England colonial people dressing as “Indians” during the Boston Tea Party to protest taxation, through the inspiration of our governmental model taken from the Iroquois confederacy. Even the name of Texas derives from the Caddo language word taysha meaning “friend” or “ally,” which in Spanish was spelled as tejas.

Nearly from the beginning, Native Peoples became stereotyped as “noble savages,” both in need of a civilizing influence and paradoxically idealized as inherently innocent and paragons of ecological responsibility. This tension continues through the ongoing struggles for native civil rights and sovereignty, and as the figures at the forefront of environmental justice movements for sustainable policies like the recent protest of the Dakota Access Pipeline at North Dakota Standing Rock Reservation.

The collective breadth of Native People’s experience calls into question national myths and popular narratives of “manifest destiny” and American exceptionalism. Furthermore, indigenous concepts of tribal governance, land stewardship, alternative cosmologies and deeper relations to the natural world are powerful and timely models for roads forward into future equitable and sustainable societies.

As David Treuer (Ojibwe) explains in The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: “If you want to know America—if you want to see it for what it was and what it is—you need to look at Indian history and at the Indian present. If you do, if we all do, we will see that all the issues posed at the founding of the country have persisted. How do the rights of the many relate to the rights of the few? What is or should be the furthest extent of federal power? How has the relationship between the government and the individual evolved? What are the limits of the executive to execute policy, and to what extent does that matter to us as we go about our daily lives? How do we reconcile the stated ideals of America as a country given to violent acts against communities and individuals? To what degree do we privilege enterprise over people? To what extent does the judiciary shape our understanding of our place as citizens in this country? To what extent should it? What are the limits to the state’s power over the people living within its borders? To ignore the history of Indians in America is to miss how power itself works.”

This month, and every month, we encourage others to explore the rich traditions of the vast spectrum of native tribes and sovereign nations. Here we highlight some books and resources by native authors from this rich and varied tradition.

Collection Highlights

Digital exhibits and resources

-

- National Archives

- Native American Heritage Month from the Library of Congress

- Native American Rights Fund (NARF)

- National Congress of American Indians

Nonfiction

The heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the present by David Treuer (Ojibwe)

The heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the present by David Treuer (Ojibwe)

The received idea of Native American history–as promulgated by books like Dee Brown’s mega-bestselling 1970 Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee–has been that American Indian history essentially ended with the 1890 massacre at Wounded Knee. Not only did one hundred fifty Sioux die at the hands of the U. S. Cavalry, the sense was, but Native civilization did as well. Growing up Ojibwe on a reservation in Minnesota, training as an anthropologist, and researching Native life past and present for his nonfiction and novels, David Treuer has uncovered a different narrative.

Shapes of Native nonfiction: Collected essays by contemporary writers edited by Elissa Washuta and Theresa Warburton

While exploring familiar legacies of personal and collective trauma and violence, these writers push, pull and break the conventional essay structure to overhaul the dominant cultural narrative that romanticize Native lives, yet deny Native emotional response.

Braiding sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer

An inspired weaving of indigenous knowledge, plant science, and personal narrative from a distinguished professor of science and a Native American whose previous book, Gathering Moss, was awarded the John Burroughs Medal for outstanding nature writing.

Memoir

Crazy Brave by Joy Harjo (Muscogee)

A memoir from the Native American poet describes her youth with an abusive stepfather, becoming a single teen mom, and how she struggled to finally find inner peace and her creative voice.

Heart Berries by Terese Marie Mailhot

Heart Berries is a powerful, poetic memoir of a woman’s coming of age on the Seabird Island Indian Reservation in the Pacific Northwest. Having survived a profoundly dysfunctional upbringing only to find herself hospitalized and facing a dual diagnosis of post traumatic stress disorder and bipolar II disorder; Terese Marie Mailhot is given a notebook and begins to write her way out of trauma.

Popular Fiction

There, There by Tommy Orange (Cheyenne – Arapaho)

“We all came to the powwow for different reasons. The messy, dangling threads of our lives got pulled into a braid–tied to the back of everything we’d been doing all along to get us here. There will be death and playing dead, there will be screams and unbearable silences, forever-silences, and a kind of time-travel, at the moment the gunshots start, when we look around and see ourselves as we are, in our regalia, and something in our blood will recoil then boil hot enough to burn through time and place and memory. We’ll go back to where we came from, when we were people running from bullets at the end of that old world. The tragedy of it all will be unspeakable, that we’ve been fighting for decades to be recognized as a present-tense people, modern and relevant, only to die in the grass wearing feathers.”

Books and islands in Ojibwe country by Louise Erdrich (Ojibwe-Chippewa)

Erdrich compellingly writes about the Ojibwe spirits and songs, language, and sorrows that have passed down through generations. Erdrich later travels to Rainy Lake, to an island of real books, the world of an exuberant eccentric and close friend to the Ojibwe, who established an extraordinary library there a hundred years ago.

Genre Fiction

Trail of Lightning by Rebecca Roanhorse (Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo)

Trail of Lightning by Rebecca Roanhorse (Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo)

While most of the world has drowned beneath the sudden rising waters of a climate apocalypse, Dinétah (formerly the Navajo reservation) has been reborn. The gods and heroes of legend walk the land, but so do monsters. Maggie Hoskie is a Dinétah monster hunter, a supernaturally gifted killer. When a small town needs help finding a missing girl, Maggie is their last best hope. But what Maggie uncovers about the monster is much more terrifying than anything she could imagine.

Walking the clouds: An anthology of indigenous science fiction edited by Grace L. Dillon

In this first-ever anthology of Indigenous science fiction Grace Dillon collects some of the finest examples of the craft with contributions by Native American, First Nations, Aboriginal Australian, and New Zealand Maori authors.

Poetry

Native voices: Indigenous American poetry, craft and conversations edited by CMarie Fuhrman and Dean Rader

Native voices: Indigenous American poetry, craft and conversations edited by CMarie Fuhrman and Dean Rader

In this groundbreaking anthology of Indigenous poetry and prose, Native poems, stories, and essays are informed with a knowledge of both what has been lost and what is being restored. It presents a diverse collection of stories told by Indigenous writers about themselves, their histories, and their present. It is a celebration of culture and the possibilities of language, in conversation with those poets and storytellers who have paved the way.

Whereas by Layli Long Soldier (Oglala Lakota)

WHEREAS confronts the coercive language of the United States government in its responses, treaties, and apologies to Native American peoples and tribes, and reflects that language in its officiousness and duplicity back on its perpetrators.

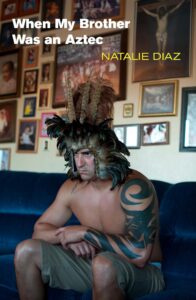

When My Brother Was an Aztec by Natalie Diaz

When My Brother Was an Aztec by Natalie Diaz

This debut collection is a fast-paced tour of Mojave life and family narrative: A sister fights for or against a brother on meth, and everyone from Antigone, Houdini, Huitzilopochtli, and Jesus is invoked and invited to hash it out. These darkly humorous poems illuminate far corners of the heart, revealing teeth, tails, and more than a few dreams.

Bone Dance: New and Selected Poems, 1965-1992 by Wendy Rose

A prolific voice in Native American writing for more than twenty years, Rose has been widely anthologized, and is the author of eight volumes of poetry. Bone Dance is a major anthology of her work, comprising selections from her previous collections along with new poems. The 56 selections move from observation of the earth to a search for one’s place and identity on it. In an introduction written for this anthology, Rose comments on the place each past collection had in her development as a poet.

Nature Poem by Tommy Pico

Nature Poem follows Teebs–a young, queer, American Indian (or NDN) poet–who can’t bring himself to write a nature poem. For the reservation-born, urban-dwelling hipster, the exercise feels stereotypical, reductive, and boring. He hates nature. He prefers city lights to the night sky.

IRL by Tommy Pico

IRL is a sweaty, summertime poem composed like a long text message. It follows Teebs, a reservation-born, queer NDN weirdo, trying to figure out his impulses/desires/history in the midst of Brooklyn rooftops, privacy in the age of the Internet, street harassment, suicide, boys boys boys, literature, colonialism, religion, leaving one’s 20s, and a love/hate relationship with English.

Two recent books I have enjoyed and recommended are:

Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History by S.C. Gwynne (winner of a Pulitzer)

and

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann

I recommend these books by Sherman Alexie:

-The absolutely true diary of a part-time Indian. (2007)

-You don’t have to say you love me : a memoir. (2017)