UT hosted this panel discussion as part of our Mental Health Promotion Week 2020. This post aims to condense and summarize what was discussed. Once the recording becomes available, that link will be shared as well. Thank you to Quynh-Huong Nguyen for moderating! The panelists included:

Q: Can you share your perspective about how Asian American (“AA”) history, particularly exclusion and racism, shape the current racialized climate with COVID-19?

There was a lot of rehashing of AA history in answering this question. Everything from the Chinese Exclusion Act to the Japanese internment camps to the murder of Vincent Chin—AA have always been portrayed as the foreigners that never quite belonged in the U.S. COVID-19 has resurfaced a lot of these sentiments. What makes it worse is that during each period in AA history, there has been a history of silence (a protection mechanism which will be discussed later on). This is all exacerbated by our head of state perpetuating these racist attitudes through terms including “Chinese virus.”

Q: Why is it important for Asians and non-Asians to know this history during this time?

The short answer is that knowing this history can better help people who have never experienced these issues to articulate what we’re feeling and to understand survival strategies, including historical assimilation and the loss of native cultures. AA history is not talked about as much and is not taught in schools.

The long answer is that racializing COVID-19 is multi-faceted and impacts AA in more ways than we realize. The history of racism in the U.S. towards individual groups is not isolated—the fact is that racial groups have all been pitted against one another. To understand the AA part of history better fosters an understanding of racial relationships between all minorities, not just within the Asian community. For example, the model minority myth has been used as an “us vs. them” mechanism to pit Asians against other minorities. But even within the Asian community, there exists a long history of “othering,” where Southeast Asians, South Asians, and Pacific Islanders often dissociate themselves from the umbrella category of “Asian.” Understanding our collective history, which includes AA history, makes it all make more sense. It helps to build community and allies. Even Andrew Yang’s recent article, which talks about how Asians now should show their American-ness, is based on the underlying assumption that being Asian American is still not American.

Q: Why is it disingenuous for someone to say calling COVID-19 the “Chinese virus” is “technically accurate”?

The one thing that every panelist agreed on is that this line of terminology perpetuates racism and is just not productive. Racism begins when we default an image of what it means to be a certain race. The harm of using terms like “Chinese virus” lies in its perpetuation of those images of certain racial groups; it suggests that Asian (specifically Chinese) people are inherently infected. These harmful phrases re-characterize the virus without lending any productive solutions. Where is the sickness spreading the fastest? In the U.S. and not in China—so why are we still fixating it on Asian/Chinese people? Using the place of origin as justification to continually tie the virus to China falls into the trap of using racialization of diseases to oppress certain minority groups. Calling the virus anything like the “Chinese virus” sounds just like an undisguised attack. This just plays off of “recycled racial anxieties” (thanks for the great phrase, Andi!) and is not only racist, but also irresponsible.

Q: What do we say to someone who says we shouldn’t be offended by this rhetoric and racism?

This could be a hard conversation to have because a lot of times people don’t expect us to say anything. After all, the AA silence is a protection measure. But, we can always start the conversations in our private spheres. For those we are close with, we should be able to tell them not to use hurtful or racist phrases. It takes no effort to switch the terminology or not be racist.

Q: What do I tell someone who excuses racism by saying “it’s just fear or ignorance”?

There’s a big difference between ignorance and willful ignorance. In this day and age, there are resources abound, especially in a university or political environment. They have people who are trying to make them listen, they have resources, they have hugely public platforms to which they have access; their decision to ignore those resources weaponizes ignorance and fear through the form of racism. The fact that more and more AA are willing to speak up about these issues makes willful ignorance all the more egregious.

Q: How should one respond to statements from other Asian friends/family members that other minority groups have it worse in America?

The bottom line here is that it’s never productive to steer the conversation towards a suffering game. If anything, this leads to self-invalidation and thoughts that we are not entitled to our feelings. We should instead be connecting through an educational conversation—there has been a long and undeniable history of oppression and racism against Asians in the U.S. But on top of that, we should remember that racialization is not isolated according to each minority group (back to an earlier point). In fact, Chinese people were first imported to America as cheap labor in response to the abolition of slavery. All racial minorities are in this together against a white supremacist system that constantly finds new ways to pit minorities against one another. What’s the use of in-fighting?

Furthermore, this type of response can be due to other lines of thought, including it being harder for some Asians to articulate what we need and what kinds of setbacks we face. This can be a result of the model minority myth, where we are so comfortable with invisibility that we don’t want to become visible—just another product of the immigrant experience, where those fleeing hardships are just humbled and happy to be in the U.S. And, as a part of a cultural phenomenon, Asians are also unwilling to appear weak, which is why so many Asians don’t like to admit that we don’t have it as good as we think.

Q: How do you keep informed about what’s happening in our community without being re-traumatized? How do you take care of yourself when you get activated by hearing or seeing violence and racism on the news?

It’s okay to limit exposure, to set boundaries; these are great first steps. But we should also remember that this is a collective trauma and we have community to lean on. We can be mindful of our own needs, but still appreciate that having a group to talk to can itself be gratifying. At the same time, having a group where you feel safe enough to not have to talk about these issues is also important. This is a good time to take a step back and spend time on other things, including cooking, socializing (virtually), reading a new book, etc.

Q: How does experiencing racism affect the mental health of your clients? Can you explain the concept of racism as a trauma?

Racism is about one dominant group keeping their power through oppression of non-dominant groups, and when we think about that in the context of COVID-19, it of course results in a pervading sense of powerlessness. When we feel triggered, our bodies automatically look for a way to protect ourselves because we feel threatened again—internalized and inter-generational trauma results in protection mechanisms including assimilation and silence as a community, but also results in depression and anxiety individually. A lot of people don’t even recognize the existence of inter-generational trauma, so the effects can be especially confusing; it’s hard for us to understand that harm can from from a place that represents safety (e.g. from our families).

A specific example of inter-generational and internalized trauma is the “colonial mentality,” where colonized people have internalized a sense of inferiority because it helps to justify their domination. The speakers here specifically referenced Pacific Islanders (Filipinos, to be exact) and how historically they have come to identify more as Hispanic than Asian. On a larger scale, these sorts of internalized and inter-generational trauma can result in the harsh lines we draw between races, and even explain the intra-racial lines we draw, where certain members of a race don’t like to be associated with their race. The result of all this internalization is that it seeps into our culture and identities. So much of our upbringing is collectivist and hard to dismantle.

Q: How have you dealt with all of this?

Bottom line: self-care! Whether it be shutting out the news, watching a mindless movie, Zoom happy hours, etc. Be mindful of others as well—if you think someone is struggling, connect with them! Asians already have a hard time articulating our feelings, so community right now is important.

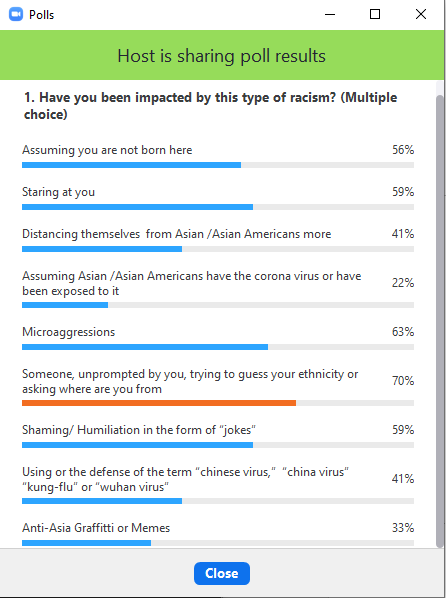

To conclude the panel, we participated in a poll:

Just based off the percentages, we can confidently say that you are not alone in this. If you are a UT student struggling with any of these issues, please reach out to Amy Tao-Foster, CMHC, any of the panelists above, or other non-UT resources. We also have additional resources, not limited to mental health, for students. If you can’t find what you need, want a friendly face to talk to, or know of more resources we can share with our community, please feel free to contact us.