I live in the middle of Cape Town – what is called City Centre – and I work about 10 kilometers away in the suburb of Claremont. The bus system doesn’t extend that far, so my mode of transportation is the MetroRail. Trains in Cape Town run on an unreliable schedule, often breaking down, getting delayed, changed, or canceled altogether. Despite the inconsistencies, the ticketing system is relatively simple. Tickets can be bought as one-way, round trip, week or month passes, for first, second or third class. The line I take – the Southern Suburbs Route – is one of the most reliable and safe. My first-class-one-month-pass costs the equivalent of $19. The purpose of the pass is of course to prevent anyone from just hopping on and off the train, and it is supposed to limit the holder to the train car which matches the class they purchase. Sometimes the cards are checked as I board and exit in the city; rarely have I seen an attendant at the station near my office. I’ve also seen people run straight past the gate attendants, jump onto moving trains, and walk between cars on the connection cables.

The reason I tell you about the train system is so you can understand that despite MetroRail’s attempts to make the train system safe and increase the sense of legitimacy around the rail system, it is still possible for people to sneak through and passengers do have to be safety conscious.

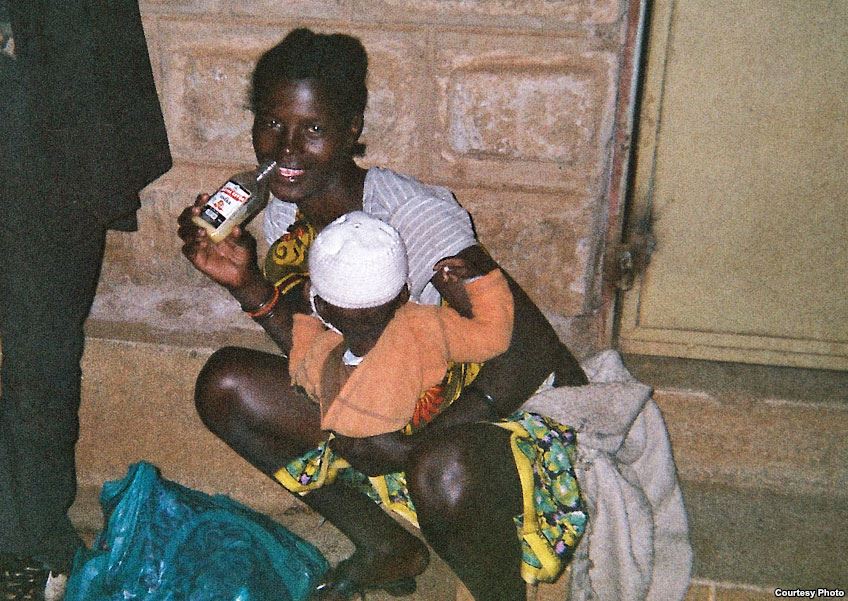

Last week I boarded the train at 5:30 p.m. leaving Newlands Station (near my office). I immediately smelled something odd, something chemical. I saw that some people had their scarves over their noses and mouths. After I took a seat, I looked across the car to see three people – a man, a woman and a teenage boy – wearing very dirty clothing, with trash bags covering their shirts. Each of them was holding a small plastic bag and was sporadically holding the bag to their mouth and nose, breathing deeply while staring forward with glazed over eyes. I was witnessing a form of substance abuse known as glue-sniffing, which is notorious in poor urban areas.

Glue-sniffing is a detrimental addiction. Children have been paralyzed by the substance; it is popular particularly for poor youth because it is inexpensive, readily available, and provides temporary sensations of happiness, pleasure and detachment. Inhaling glue also can also suppress feelings of hunger and cold. On that particular night when I rode the train, it was supposed to get down to six degrees Celsius – 43 degrees Fahrenheit.

The expressions on their faces were very disturbing. I could tell immediately that wherever their minds were, they were not present with us, sitting on the bench in the train. Perhaps it was only my imagination but I felt dizzy just being so close to them. Though I couldn’t understand their conversation (they were speaking Afrikaans), other passengers were clearly trying to talk them into stopping or leaving the car. At first I didn’t realize one of the three was a child because of the fatigue on his face. When it hit me that this was a young boy, I felt even sicker to my stomach. Youth make up the largest demographic to abuse this substance, which makes it even more tragic. It damages the lungs, the kidneys, and the nervous system, among other organs. It also makes the user very vulnerable to abuse and injury, as the chemicals can knock a child out for hours at a time.

The conversation between other passengers and the three users began escalating. At one point, the child stood up as if to lunge toward someone on the opposite side of the car, but the older man pulled him back into his seat. All three looked angry and confused. An older woman sitting near them began, in a strict motherly voice, reprimanding the adults for allowing a child to sniff glue. She asked how they could do this to a young life, allowing him to waste himself away. The man began arguing with the woman, again speaking in Afrikaans. It was clear that a confrontation would occur if nothing preventative was done. When the train stopped at the next station, one woman went to the door and yelled for security. Having to physically pull the three off the train, a few guards managed to take them away. The woman was demanding they call social services for the child. When they had disembarked, she apologized repeatedly for making a scene. She continued to repeat, “it’s a young life, and it is so sad, no one ever says anything about these things.”

So what can be done? If we’re being honest, in all likelihood the three users were thrown out on the street to deal with the cold. Social services were probably not called. Maybe the glue was taken from them, but with its easy accessibility they likely had a new stock within the hour. Regulations to limit sales of glue to children are in place but are difficult, if not impossible, to enforce. Still, simply stopping sales will not decrease the demand from children for something like this – not when they are starving and freezing at night. The problems are clearly much deeper and more fundamental.

As I leave work today to catch the train, I will certainly keep an eye out for a similar situation. I may not see substance abuse on the train again, but the reality of the situation is pervasive – people are still very desperate in all parts of South Africa – and the tragedies of poverty affect us all.