-Rachel Hegab, Louisiana Tech Univ.

, Filed Under: 2016, austin, fun

, Filed Under: 2016, cancer, research, texas4000, ut austin

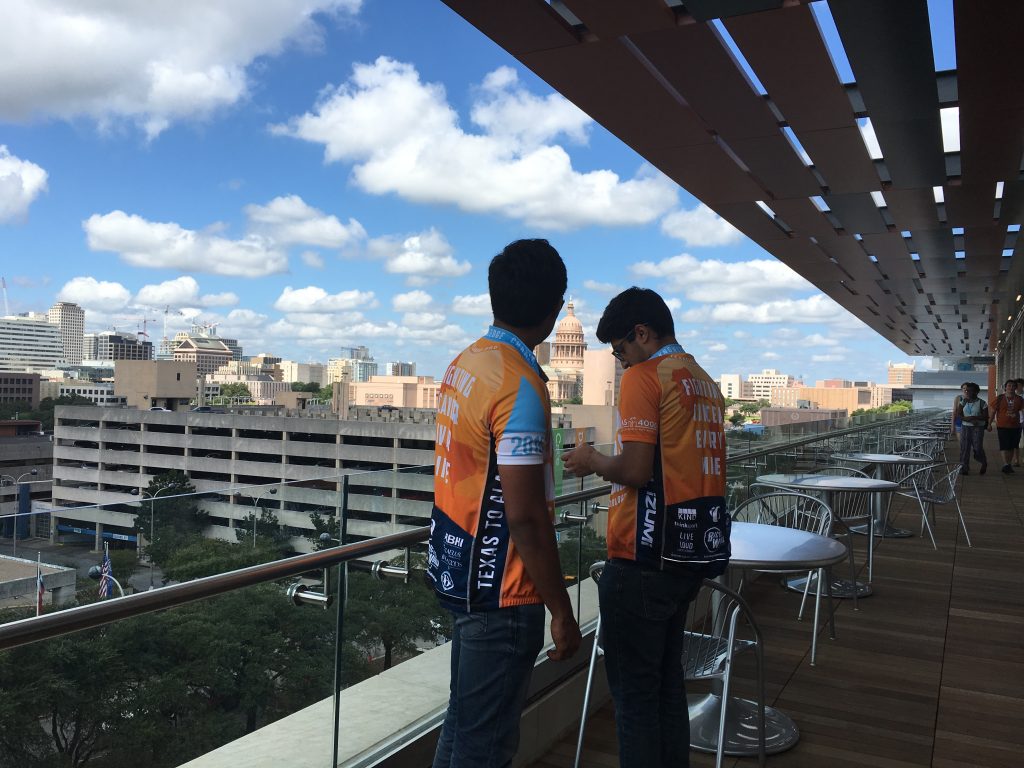

This summer we were fortunate to be able visit the Dell Medical School, which opened this year and is welcoming their first 50 students. However, there are still a few buildings under construction, and other administrative things that are yet to be completed. Nonetheless, judging from my experience touring the school alongside the Texas 4000 riders, the Medical School is poised to do great things and accomplish their lofty goals, one of which is transforming the way academic medicine is done. It is a breath of fresh air to hear about people trying to change the way things are done for the better, and have the aspirations of making not only communities better, but ultimately the world a better place. What stood out the most from this visit was that the people who are working tirelessly to get this Medical School up and running understand that the only way to accomplish their goals is with the help of their community, and through their collaboration. A big component of their plan to achieve some of their goals is having platforms through which they can get feedback from the community on ways certain things can be done better. With this information they plan to investigate the efficacy of these suggestions and hopefully publish and implement them if they are proven to be more efficient. With the hope that others will follow their lead. Being a researcher it is music to my ears hearing that some sort of data will be collected to prove what works and what doesn’t.

This was said by the surgeon Bernard Fisher who was instrumental in proving that the radical mastectomy was not the most efficient way of treating breast cancer. Without a doubt the visit to the medical school was an eye opening experience as was this entire summer at The University of Texas at Austin.

-Adiel Hernandez, Univ. of Miami

, Filed Under: 2016, reflections, research

Growing up as a kid, science class was taught based on the facts that we have gained throughout historical records. Did Sir Isaac Newton record study after study and write the about his laws of motion to describe the effects of gravity and momentum? Yes, that is a fact. Did Galileo Galilei become the first person to openly challenge the Catholic Church and state that the sun is truly the center of our solar system not the Earth? Yes, that is a fact. These were revolutionary ideas in their respective eras and the only way that people were able to determine these ideas as fact was through numerous replications of their experiments by different people all across the globe.

Every scientist wants their research to go down in the history books and to set the standards for their respective fields like what Newton and Galileo did for their fields. This burning passion though skews some lines about the number of times experiments should be replicated before being published. Some people pump out data too quickly so not all of the possible issues have been troubleshot yet, so other scientists might doubt the validity of the results. This means that science actually takes a really, really long time before anything can even be presented to the scientific community.

Some researchers are willing to even go to extraordinary measures like faking their lab results just so they can be published have five minutes of fame and glory. The only problem is that in science they have systems to catch these frauds. People have designated jobs to repeat people’s scientific experiments in order to prove their validity. It’s fairly easy to catch them too because after a few people talk and agree that the results are not replicable the publication is tainted. This is the worst thing that can happen to scientist; once your reputation is tainted it’s nearly impossible to ever recover. Not only is your reputation important, but also whoever your scientific mentor is really impacts how much faith people put into your findings.

The REU program had a really extensive discussion one of the first weeks over the importance of producing truthful, replicable results. The biggest example that was hammered home was the effects of one graduate student at a Japanese university that produced some truly revolutionary research. Nobody could reproduce this data. People investigated further and further and found that the images that this researcher had published were actually the combination of two totally different samples that were doctored together. There was outrage in the scientific community. The woman had her PhD revoked by her university and her entire lab’s careers were tarnished and they were scoffed at for being associated with the fraud. The woman and her co-author were both so ashamed by the backlash that they both committed suicide shorty after.

Not only does the number of times that tests have to be run hinder the scientific process, but the number of safety regulations that have been implemented recently has really slowed things down. Before, scientists would test on animals and even humans freely without too many restrictions, now for any similar testing any proposed experiments have to be reviewed by an entire board at the university. The whole process has turned science into a much safer endeavor for the patients involved as well as the environment. However, the drawbacks are slowing down the timeline for potential products and drugs that could protect the world and save thousands of lives. Think about how far you would go; how many rules would you bend to make your mark on science and save the world?

-Grant Ashby, Georgia Tech