When British defense secretary Michael Fallon publicly stated last week that the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were at high risk to be drawn into armed conflict by Vladimir Putin, much like Ukraine had been over the past year, and that NATO had to prepare for Russian aggression, the media in the West took note. But to people in the Baltic region, this was old news, as I experienced first-hand during a visit last Fall when I had a number of discussions on the topic with colleagues at the universities of Tartu and Tallinn. They confirmed that the Russian covert campaign Fallon warned against in fact had already begun.

Estonia is a classic case of a small country that has been tossed around by history. Estonia was dominated by foreign powers for most of the last millennium: Danes, Germans, Swedes, and Russians, both of the Tsarist (1710-1918) and Soviet flavors (1940-41; 1944-91). In spite of that, Estonia has been able to maintain a cultural and linguistic identity over the centuries which forms the core of its national identity today. To Estonians, the Russian legacy weighs particularly heavily as Tsarist Russia began to russianize Estonia in the late 19th century, the construction of the highly visible Russian-Orthodox Alexander Nevsky Cathedral occupying the symbolic spot across from the Toompea Castle being the pinnacle of that effort.

Russian-Orthodox Alexander Nevsky Cathedral (1894-1900) on the symbolic Toompea Hill in Tallinn, Estonia.

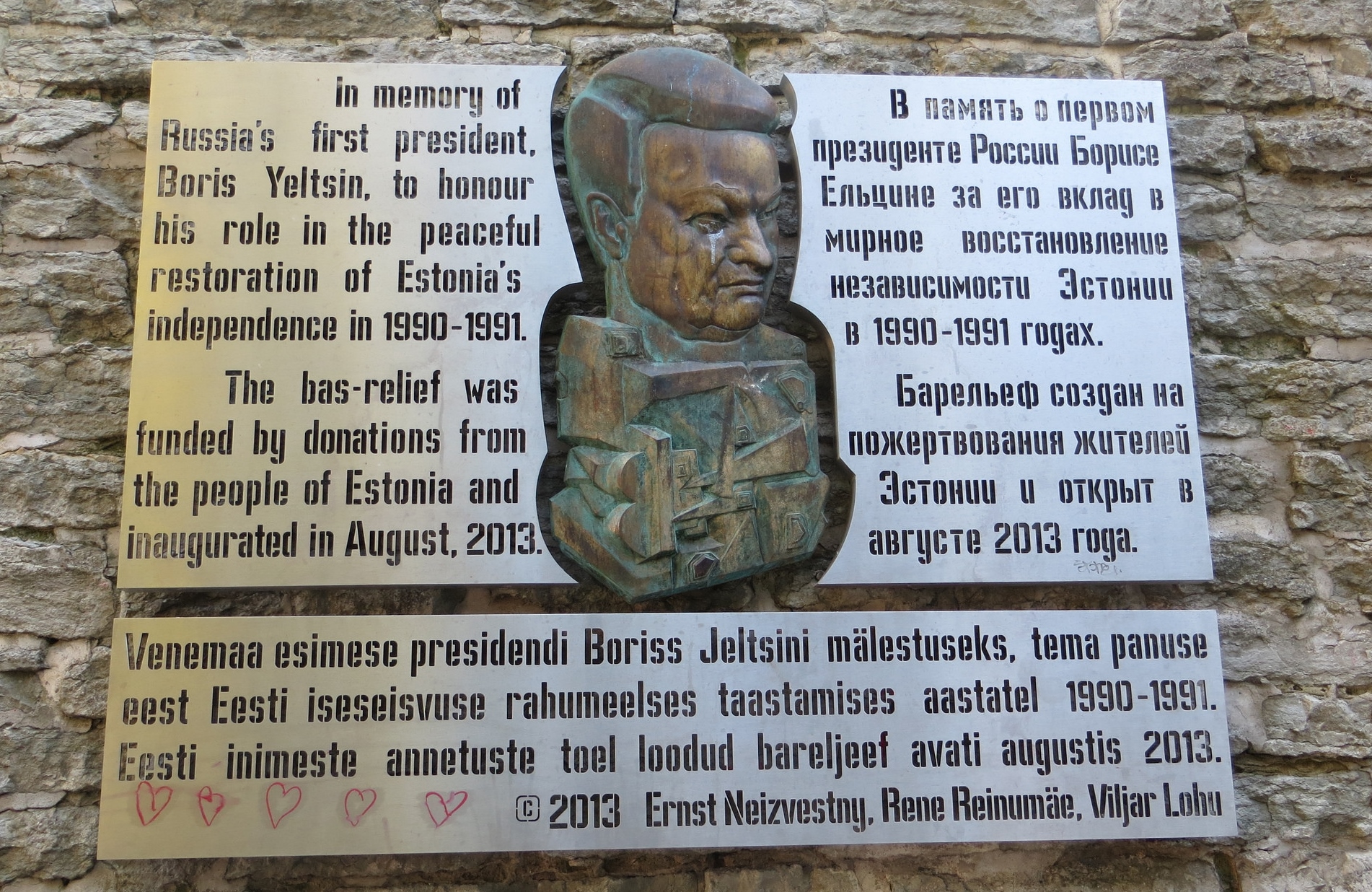

Estonia was traumatized in particular by the Soviet occupation of 1940 and its subsequent integration into the Soviet Union. While foreign control over the centuries, even by Tsarist Russia, had been comparatively benign, Soviet rule was ruthless and oppressive. The Estonian response after independence in 1991 was a strong anti-Russian backlash and assertive policies to pursue integration into the Western economic and military systems by seeking membership in Nato and the European Union and by joining the Eurozone. The only Russian celebrated in Estonia today seems to be Boris Yeltsin whose supportive role in Estonia’s quest for independence in 1991 was recognized by a plaque in his memory in 2013–which has a distinct anti-Putin edge. The plaque was affixed to the bottom of the massive wall that fortifies Toompea Hill–which since the Middle Ages had been the locus of foreign power.

But the most obvious legacy of almost 50 years of Soviet rule is a large ethnic Russian population. The Soviet Union used massive forced migration to pursue its goals. According to the Estonian government, the Soviets killed or deported about 60,000 Estonians, or more than five percent of Estonia’s population, between 1940 and 1949. At the same time, a large number of Russians relocated to Estonia, both voluntarily and forcibly. While in 1934, 88.1% of residents of Estonia were ethnic Estonians, their share had dwindled to 61.5% in 1989.

Estonian independence turned the privileged Russian population into losers. Restrictive citizenship laws which are based on the ius sanguinis, disenfranchised many Russians living in Estonia: ethnic Russians, even those born in Estonia, were not automatically given Estonian citizenship but rather had to undergo a naturalization process that required knowledge of the Estonian Language. This turned out to be an insurmountable burden for many Russians. As a result, there were many stateless people in Estonia whom Estonia euphemistically calls “people with undetermined citizenship.” Ironically, it is the European Union which, through its European Commission Against Racism and Intolerance, pressured Estonia to improve the plight of the Russian population in Estonia. According to the Estonian government, the situation has vastly improved: while in 1992, 32% of residents of Estonia were stateless, in 2014 only 6.5% were, with another 9.2% holding foreign passports, mostly from other former Soviet republics.

While the issue of “people with undetermined citizenship” appears close to resolution, the integration of ethnic Russians remains a critical issue. An estimated 24% of the resident population are ethnic Russians, and they mostly represent the underprivileged classes in Estonian society. The concentration of Russians is particularly high in urban areas: in Tallinn, the capital, perhaps half the population is Russian, and in the Narva region along the Russian border almost the entire population is Russian–which creates an opportunity for Putin to unfold a similar scenario as in Eastern Ukraine.

This constellation will give Putin ample talking points to repeat what he is currently doing in Ukraine (and what he had done in Georgia before), particularly as Estonia has not dealt with the Russian minority in an exemplary fashion. The pattern is as simple as it is predictable: creating border incidents, developing a rhetoric of assisting beleaguered ethnic Russians in a former Soviet republic, infiltrating the border area with Russian special units in disguise to stir unrest, creating a phony and fabricated resistance and separatist movement, gradually occupying territories and integrating them into his Greater Russia.

One of the legacies left to us by Soviet Communism is the fiction of international brotherhood which supersedes nationalistic divisions characteristic of capitalist societies. The implosion of Yugoslavia with all the resulting ethnic conflicts speaks to that. The Soviet policy of settling ethnic Russians in far-flung parts of the Soviet empire is another such legacy. It creates ethnic conflict in so many of the former Soviet republics, and even in areas that lie within the Russian Federation. The Baltic states today very much are afflicted by these Soviet settlement policies–and they create an opportunity for Putin to justify his Greater Russia rhetoric.

Conditions in Estonia are ripe for Putin’s strategy to unfold. In fact, stage one has already begun. Russia has been creating small border incidents with all Baltic states as well as with Finland, most commonly air space violations. The most egregious so far has been the capture and abduction of Eston Kohver, an officer of the Estonian Internal Security Service, from Estonian territory on September 5, 2014. Kohver still is in Russian custody at this writing.

Which gets us back to Mr. Fallon’s point. It appears likely that Putin will employ the same strategy in the Baltic states that worked so well in Georgia and Ukraine. In Georgia and Ukraine, Western powers could claim that their interests were not directly at stake. The difference is that the Baltic states are members of Nato, as is Poland, for that matter. We now know that managing Putin’s aggressions after the fact is futile. Yes, Nato promised not to station its troops on the former Soviet sphere of influence. But Russia also guaranteed Ukraine’s territorial integrity in 1994 in exchange for Ukraine giving up the nuclear weapons it had inherited from Soviet times. It is now time for Nato to increase its commitment to the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Baltic states, before Putin has a chance to unfold his time-tested strategy on them.

Postscript added on March 2, 2015: The looming conflict with Russia also overshadowed yesterday’s parliamentary elections in Estonia. In the media, the outcome was represented as a victory for the governing Reform Party. But their coalition with the Social Democrats actually lost the majority in parliament as support for both parties declined slightly. One of the factors is that two new parties will be represented in parliament. Most importantly, the pro-Russia Center Party gained some votes and now enjoys support from 24.8% of the electorate (24% of residents of Estonia are ethnic Russians) and will continue be the second-largest party. It is likely that the Center Party will remain the main opposition party. The concern is that Putin will be able to use both the large number of ethnic Russians and the political support they have within Estonia as a wedge issue.