By María Mercedes Gómez, Graduate student at the UT Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies

What is democracy? What is the relationship between democracy, security, and gender? This summer working with International IDEA has made me consider deeper ways to understand these concepts. Although I am Colombian and I have lived in Mexico many years of my life, living in Panama has taught me that every Latin American country is unique. Every day has been a constant discovery—from learning how to take public transportation, which products are best in the grocery store, and how to dress for the office in a Central American country to learning how to interact with people from across Latin America in the office.

I am working for International IDEA´s Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean. My coworkers are Argentinian, Chilean, Colombian, Panamanian, and Peruvian. It has been quite an enriching work experience in which everyone has shown the disposition for me to develop interesting projects and learn the dynamics of how nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) work. Panama is a country with a great disposition to receive international professionals, and it is located in a very strategic geographic position to address regional issues for Latin America. This is one of the reasons many NGOs and IGOs are located here. It is a great place to connect and interact with people from different organizations and brainstorm ideas for peace, democracy, and constitutional building in the region.

International IDEA focuses on four main topics in the Latin America region: electoral integrity, preventing democratic backsliding, security and democracy, and gender and democracy. Most recently it has also focused on digitalization and democratic resilience. Before coming to Panama, I researched democratic resilience which showed me how Latin America is a key region that is keeping democracy alive by questioning the imbalances between citizens and state. During my internship, I have been working on two other projects related to the gender and security pillars of IDEA’s work.

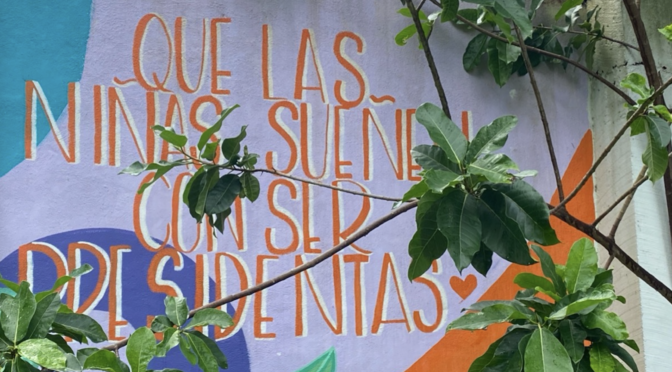

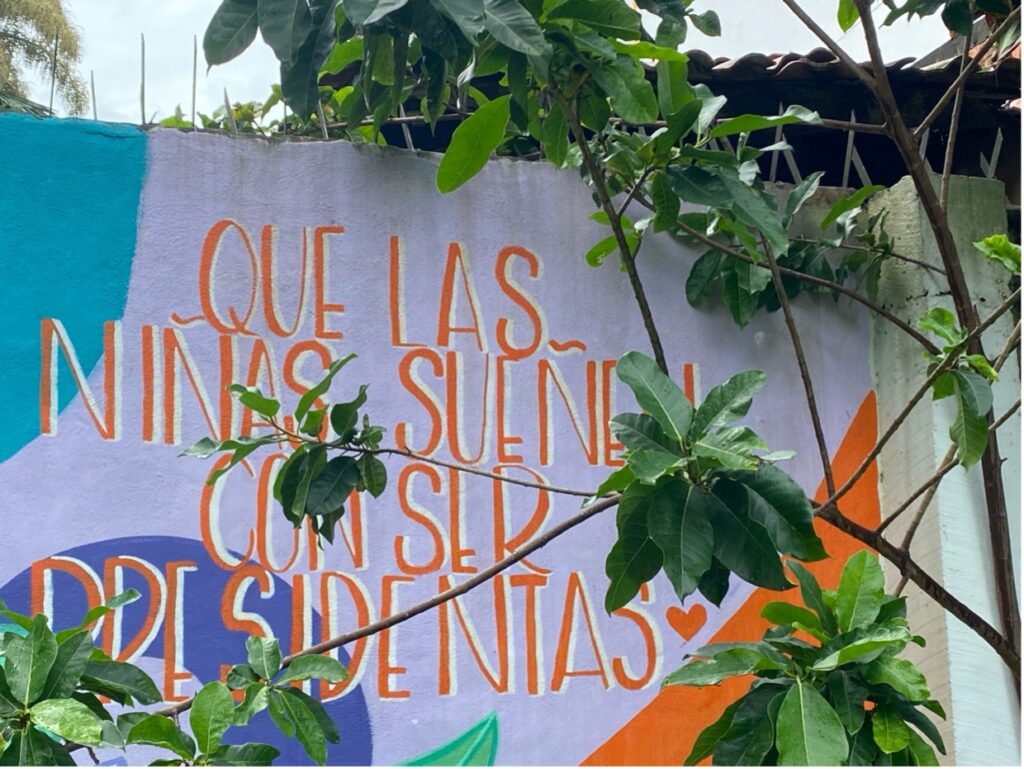

In terms of gender and democracy, I have learned that Latin America has many paradoxes on the subject. Latin America is a vanguard in the promotion and transformation of women’s political participation, as the Americas have the highest proportion of women in government positions and legislative bodies, surpassing Europe. Of the 26 countries we analyzed in the Latin America region, 11 have been governed by women (42%). Most of these countries have implemented a system of quotas which is thought to improve women’s access to these positions. Interestingly, though, many of the women who have governed their countries have not obtained power through democratic elections, instead reaching these positions by being appointed by a committee in a moment of instability or a leadership absence in the country. The ones who have reached power through democratic elections usually have a connection to an ex-president, for example being their wife, daughter, or right hand in government.

From 2007-2014 the wave of elected female presidents took place. However, since then, a return to conservatism has taken place and there are fewer female presidents in the region than there were in prior years. Further, most female presidents do not continue in politics after their presidency. This raises many questions to be explored in how to increase and sustain women’s representation in government. Nonetheless, there are new leaders and generations of women who can change this democratic deterioration.

Regarding security and democracy, IDEA is investigating the relationship between these two concepts. Security is a geopolitical concept that typically focuses on “human security.” However, human security does not necessarily refer to basic human rights such as access to water or housing but to physical security. Due to a militaristic orientation and a post-Cold War vision, states in many cases considered that their priority was protection from internal attack. This has affected the ways in which countries balance security and social policies.

It cannot be overlooked that Latin American countries have high levels of inequality which, on the one hand, are associated with criminality and, on the other, create an imbalance in those who are criminalized by the state. In Latin American countries, there is a structural trap in which the high levels of poverty and inequality produce violence towards minority groups and higher levels of criminality. This makes us look into cases like El Salvador and Nicaragua which are not considered democracies by International IDEA, but they help us analyze the relationship between security and democracy. Other cases like Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, and Uruguay present other challenges to consider like how to respond to the emergence of “criminal politics” and how to create accountability mechanisms for corrupt governments.

Criminal politics refers to the relationship between states and drug trafficking. In the last 20 years, drug trafficking has transformed the relationship between the legal and illegal worlds in Latin America and globally, creating a co-dependence between these two worlds. Criminal politics has profoundly transformed the way countries function and structure their political and economic interactions. This raises important questions on how to think about security and maintain democracy amid these dynamics that are developing worldwide.

Accountability likewise is an indicator of the quality of democracy and a way of strengthening politics. It is both a form of political control and a form of participation in public policy and social mobilization. It seeks to encourage citizen participation through structures outside elections alone. A representative democracy is one in which there is accountability over government officials even after their elected, and thus they are responsive to citizen needs and demands. Such a system creates mechanisms to create more democratic societies and a closer relation between states and citizens.

I am very excited to see the learning and professional experience that will come from our continued research in these areas.