By Mitchel McCormick, Graduate student at the UT LBJ School of Public Affairs

The Embedded Scholars’ experience in Panama City, Panama, proved to be both challenging and rewarding. Challenging because being an intern after working full-time for six years is a significant adjustment. Doing all of this in a second language abroad makes it even more compelling. Rewarding because of the quality of the work I had the opportunity to witness, the skills of the CID Gallup staff, and the opportunity to work with a creative and sharp team both at CID Gallup and UT. At CID Gallup, I held several different roles, some uniquely tailored to the company and others involving collaboration with UT students on a research study related to the experience of migrants across Latin America.

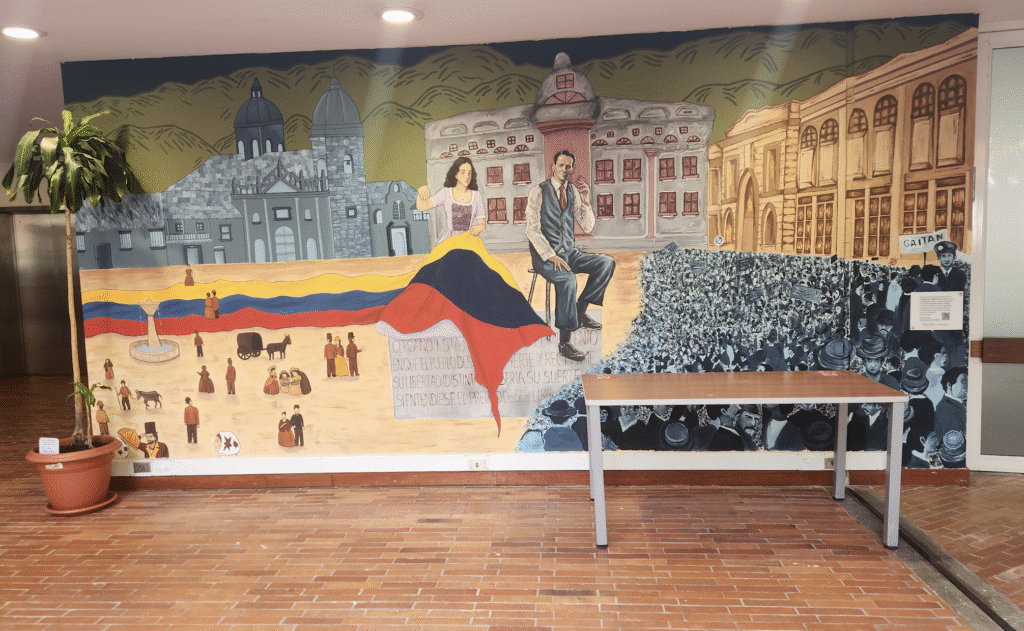

The migrant study focuses on interviewing migrants, primarily Venezuelans, about their experiences in Panama and Colombia. This study is a collaboration with CID Gallup. To recruit, we were required to ask people on the street if they were migrants. So, as a white, heterosexual cisgender man who is well-pinned as being from the United States, a certain awkwardness existed in the recruitment stage for me. Fortunately, most people were receptive, and we were able to find people willing to participate in the focus groups in Panama and Colombia. We conducted two focus groups in Bogotá, Colombia, during which I had the opportunity to travel for a few days.

Overall, the experience of listening to and learning from migrants regarding their lived experiences and relationships with national and local governments, as well as their general experiences with public policies, was truly beneficial in understanding the challenges and obstacles many migrants face. Through the migrant study, I also gained experience in the day-to-day work of conducting large-scale research studies, such as this one, with tasks including transcribing interviews and writing narratives based on the recordings and responses from focus groups.

CID Gallup conducts field surveys the old-school way: brick by brick, layer by layer, house by house. They walk up and down the streets, calling out to anyone who will listen to them on a variety of issues, ranging from presidential approval to their feelings about the Panama Canal or relations with the United States. To my surprise, many people are open to this and willing to engage with the survey. Built over 40 years of work, CID Gallup has a strong reputation in Panama, and many survey participants are familiar with their work.

Survey work is hard. First, Panama is humid—very humid. It can also be very sunny. It also rains just about every day in June. You can see the challenges of conducting a survey that exceeds 25 minutes and can include over 100 questions. Asking people this number of questions and to devote this much time is a tall ask of people. Yet, people do it, and with tremendous success.

The surveys were one of the most interesting elements of my internship. Because I primarily worked on analysis and narrative building at CID Gallup, I wanted to see the process of data collection. This is where the travel to the field to conduct surveys with Arelis came into play. Arelis—one of the nicest people around—serves as the supervisor for CID Gallup’s field surveys. After one trip to the field with the surveyors, I understood how tireless and hardworking they are.

Perhaps the most important and rewarding aspect of this fieldwork was the opportunity to visit some of the smaller places, such as towns outside Panama City or hillside villages near Colón. These trips provided me with a better understanding of the natural beauty of the landscape and the diversity of the people in Panama.

I primarily worked on the analysis side of things at CID Gallup. After the data is collected, it goes through a “cleaning” phase. The data cleaning phase involves separating and organizing the data collected by questions. Sounds easy enough to do. Right? Not really. Imagine having 80-100 questions. Then, the variety of answers. Some questions have 5-6 options. Depending on how you answer that question, you get an open-ended question. Then people can get into the details.

Having the opportunity to observe how to conduct surveys is invaluable, as well as watching and learning from colleagues during the various stages of a study, from development to analysis. After the information is cleaned and organized, it exists in various forms, such as tables, graphs, and charts. From here, I receive the task of conducting the analysis. I want to find narratives by age, sex, geography, and education level and write them based on the relevant information.

Are people with higher education levels more concerned about the relationship between Panama and the United States? What percentage of Panamanians have a favorable view of the United States? Or China? Etc. Exploring these questions is ultimately an analytical exercise, using inductive reasoning based on the collected data to make observations.

One project we were all able to contribute to collaboratively was for the PNUD, or the United Nations Development Programme. This project we saw develop from the early stages of development, allowing us to witness the process CID Gallup goes through in developing a project and getting it prepared to be executed in the field and subsequently analyzed.

The most rewarding aspect of this was the opportunity for all of us—undergraduates, graduates, and CID Gallup staff—to work together collaboratively. I found it insightful to see how everyone approached a problem. Simply put, it was an opportunity to see different personalities and work styles all at once.

In my opinion, public surveys and democracy are closely intertwined. Understanding how your population feels about a particular issue is crucial for making effective policy decisions as a legislator or leader. Being able to contribute—whether through observation, analysis, or contributing to a migrant study—I believe that the experience of collecting data to inform public policy is an essential part of any healthy democracy. The collection and free flow of data, thought, and analysis are critical to any democracy, as this is how discoveries and progress lead to the betterment of all people.

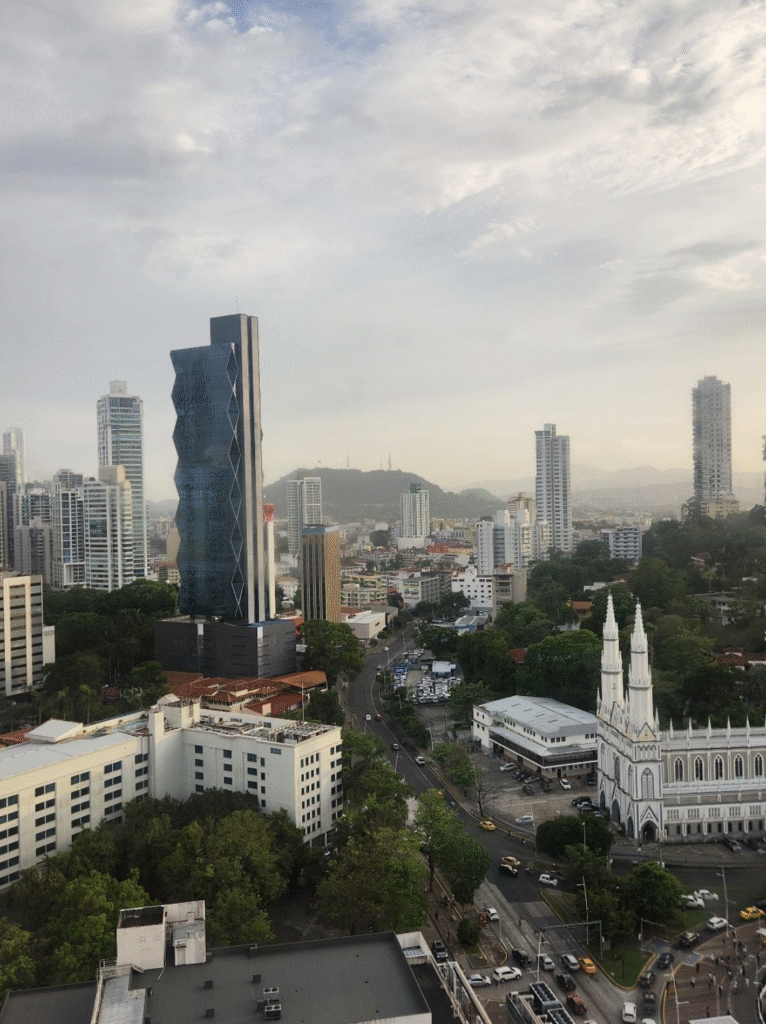

Panama City is an interesting place. You can see the influence of the United States and other cultures that have passed through the city at different times in its history. It wasn’t always what it is today. For a period, as Carlos Denton (founder of CID Gallup) says, it was a place to “sin.” Think Havana of the 1950s—or the film Godfather II, right before it all got very, very dark for the Corleone family.

Personally, being in Panama was extremely rewarding. I learned a great deal about myself and my comfort level outside the United States. I previously spent a considerable amount of time in Mexico as a student and young professional; I can tell you that I am not the same person I was then as I am now. Nevertheless, my time in Panama was more challenging than I had expected.

My primary takeaway from the experience is that it is beneficial to continually challenge oneself, whether by living abroad or working in different fields of interest. My second major takeaway is the rewarding opportunity to work with the Embedded Scholars team at CID Gallup in Panama: Doug, Olivia, Salomé, Siyona, and, in addition, Lucas Elkins. I learned something from each of them and enjoyed sharing the experience of Panama with them.