By Francisco Alvarado-Quiroz, Graduate student at the UT LBJ School of Public Affairs

I knew very little about Panama before arriving in early June. From what I remembered from classrooms and books, there was a canal the French started, and the Americans finished. Carter gave it back. The United States invaded in 1989, and now the capital city is awash with investment money building a skyline akin to Miami or Hong Kong. There is, of course, a lot more to the story. And in my four weeks here the team at IDEA has shown us Panama’s long effort to form a durable democratic government, and the United States’ involvement.

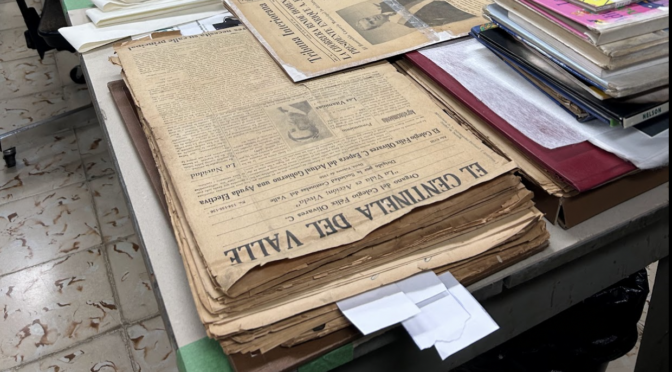

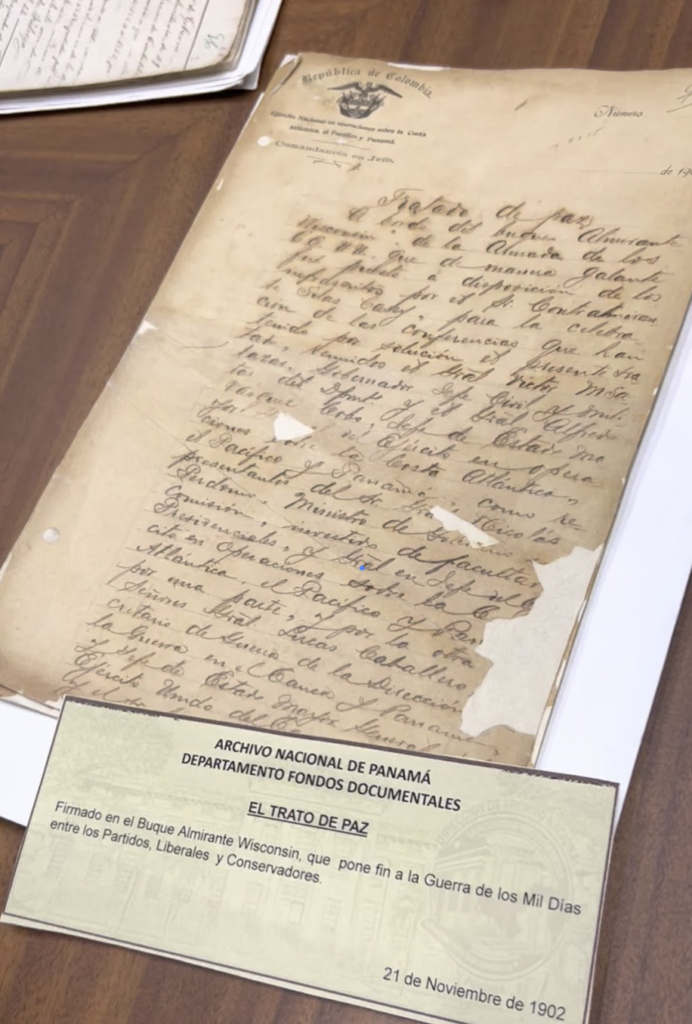

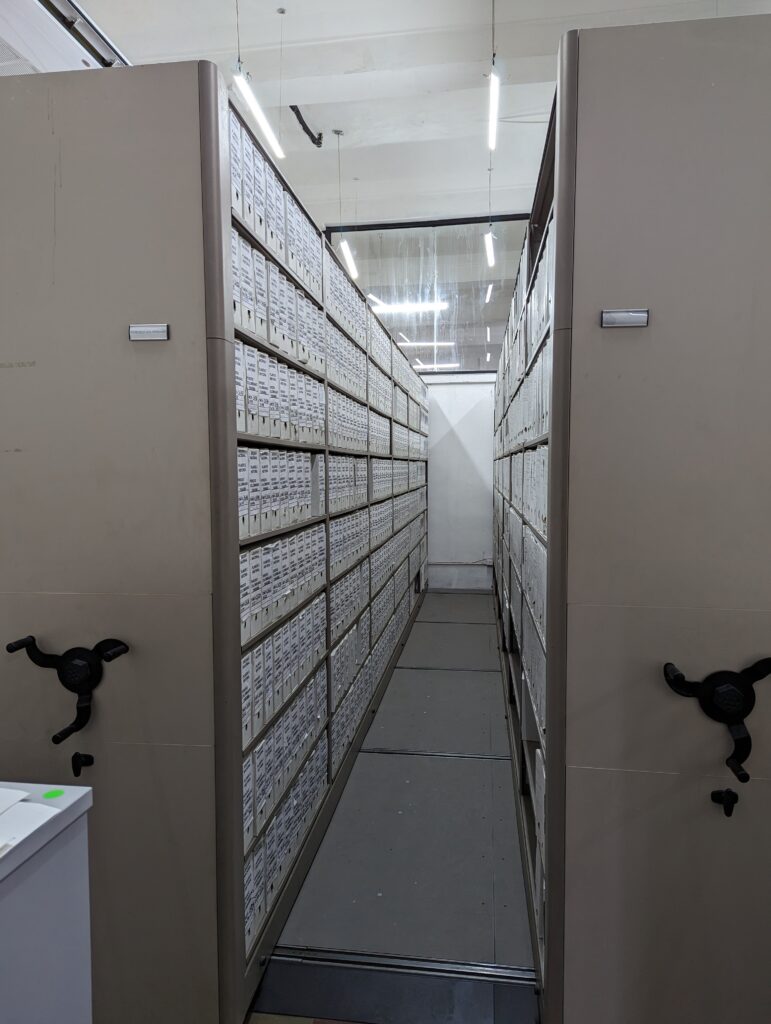

Shortly after my arrival, the team took us to the National Library. We were shown copies of the declaration of independence from Spain (when Panama was still part of Colombia) in 1821 and Panama’s declaration of independence from Colombia dating back to 1903. In that instance, American gunboats helped to back Panama’s claim to independence.

Of course, the United States was paid handsomely for its services. The Canal Zone, extending five miles on either side of the canal and stretching from Colon on the Atlantic to Panama City on the Pacific was, functionally speaking, a U.S. territory. American laws enforced by American police and courts, all under the protection of the U.S. military. All of this, in perpetuity, for $250,000 a year in rent.

Now under new management, thousands of people labored to finish the canal. People from all over the world (although most of the digging was done by men from Jamaica, the West Indies, and other parts of the Caribbean) arrived to take part in the construction. The Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interoceanique went bankrupt in nine years. The new Isthmian Canal Commission finished construction in ten. Some 30,000 lives had been lost in the quest to divide the land to unite the world.

The historic first crossing of the canal occurred to little fanfare in 1914, shortly after the outbreak of the First World War. When the giant locks at Gatun and Miraflores lifted the first ships over the Continental divide, the tension surrounding U.S. control began to simmer, until they boiled over a few decades later.

The International IDEA staff took us to a building formally known as Balboa High School, within the former Canal Zone. Outside of this building, in 1964, Panamanian students made the overwhelmingly reasonable request for the Panamanian flag to be flown alongside the U.S. flag. After all, President Kennedy had ordered such an arrangement but was assassinated before his orders could be carried out.

A scuffle broke out between American students, Panamanian students, and American canal police. In the struggle, the Panamanian flag was torn. Tensions exploded, and violence took over the Canal Zone. The U.S. Army responded and, after three days, three Americans and 21 Panamanians were dead. Presidents Johnson and Robles launched talks to remake the American-Panamanian relationship to the canal but the effort stalled. A successful effort to remake the relationship was not completed until 1977, when Presidents Carter and Torrijos agreed to the gradual turnover of the canal to Panamanian control.

Today, the high school houses the archives of the Autoridad del Canal de Panama, which took over operations in 1999. Outside of this building stands a monument to 21 Panamanians who were killed during the protests in 1964. The flagpole at the center of the 1966 uprising is still there, not far from its original location, a Panamanian flag fluttering in the breeze.

Events outside of the Canal Zone during this time were equally turbulent. A struggle for a representative government broke out almost immediately after Panama became independent from Colombia in 1903. Powerful oligarchs, the main beneficiaries of the country’s economic engine, controlled the government. The first of many coup d’états removed President Arnulfo Arias from power in 1941. He would go on to be removed from office by the military two more times.

There were bright spots. On my favorite outing with the IDEA team, we visited the home and legal offices of Ricardo Joaquín Alfaro—a lawyer who served as President and went on to a long and distinguished diplomatic career. Alfaro was Panama’s delegate to the meeting held in San Francisco that would establish the United Nations in 1945. There he was charged with helping to draft the UN Charter in Spanish. He went on to advocate for human rights, serving on the International Court of Justice, and serving as chairman of the committee that wrote the UN’s Convention on Genocide in 1948.

His home is now partly a museum and archive. His four-story terraced home is dwarfed by the new high rises in his area. The home’s thick walls make the inside almost soundproof. The silent and peaceful inside of Alfaro’s office is filled with mementos. A signed picture of President Roosevelt. Souvenirs from a visit to the Lincoln Memorial, a bust of Benito Juarez. A picture of him sitting in a garden with John D. Rockefeller Jr.

Outside of his office is Alfaro’s official diplomatic uniform, complete with a plumed bicorne, cape, and sword, worn at formal balls and when he presented his credentials as Panama’s Ambassador to the United States. (As I stood next to it someone mentioned it would fit me, but I restrained myself from asking to try on the hat or swing the sword over my head.) Also present was Alfaro’s grandson whom I am grateful to for letting us into his home.

Alfaro’s efforts overseas did not always translate to positive developments at home. A military junta removed President Arias for the last time in 1968 and ruled until the United States invaded in 1989.

The invasion began on December 20, 1989, and lasted until January 31, 1990. The invasion, given the heady name of Operation Just Cause, was launched for many reasons. The military leader of Panama at the time, who served as a CIA asset, Manuel Noriega had been caught trafficking drugs. He had survived multiple coups and had annulled the results of an election he most likely lost. The invasion, however, was launched unilaterally, without the approval of any international body. Not the United Nations nor the Organization of American States.

We were told all of this as we sat in the offices of the 20th of December Commission, which is tasked with counting how many Panamanian civilians were killed during the invasion. To this day, no one is sure how many died. Estimates run from 200 to 3,000. The trauma is national. American forces landed at Colon and Panama City and advanced across the Canal Zone. The best metaphor for the emotions the invasion brings to Panamanians is to imagine the feelings Americans get when we visit USS Arizona in Hawaii or the 9/11 Memorial in New York and combine them.

Everyone who is old enough to be my parents has vivid memories of ’89. The captain of a tour boat I was on told me he was the skipper a shrimp fishing boat the day bombs started falling in Panama City. He said his crew crowded around the radio to hear the news, but no one wanted to believe the United States had really invaded.

Add to this another complication. Panama’s current democratic system, the one all of the people at IDEA and the Electoral Tribunal are working to preserve and improve, dates back the government formed in the wake of Noriega’s removal. “Of course, no one wanted Noriega to stay forever,” an uber driver told me, “But the invasion was a nightmare.”

Therein lies the Panamanian puzzle. The canal, the product of 19th century colonial intrigue by French and American actors, now sits proudly as the country’s crown jewel, responsible for roughly 5% of the country’s GDP. Its current democracy developed in the wake of a unilateral intervention. The good, it appears, must always come with the bad.

And so, through all of the tumult, herculean construction projects, international intrigue, and global trade, sits this small republic of 4 million people brimming with history and an over 100-yearlong struggle for democracy.

For this new wealth of knowledge, I must thank the team at International IDEA’s Panama Office who felt honor bound to teach us a little about their country. I am forever thankful.