Getting started—simply

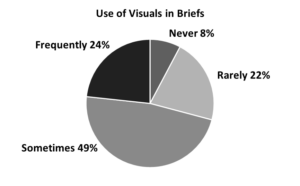

Two previous columns discussed visuals as valuable tools for persuasion in briefs and how brief writers could overcome obstacles to using visuals. This month I offer some practical tips for using visuals and some simple ideas for creating them.

Two experienced practitioners-turned-legal-writing professors have written an excellent article full of good advice: “Art”-iculating the Analysis: Systemizing the Decision to Use Visuals as Legal Reasoning, by Steve Johansen and Ruth Anne Robbins.[1] They helpfully divide visuals into three categories: Organizational visuals such as bullet lists, timelines, and tables—even the Table of Contents; interpretive visuals such as flow charts, pie charts, and Venn diagrams; and representative visuals such as images and maps. They then ask writers to imagine the legal argument visually and identify what type of visual would aid the reasoning.[2]

Once you’ve decided to use a visual, Johansen and Robbins say it’s worth assessing where the visual falls on a “usefulness” continuum. On one end are merely decorative visuals—eye-catching but with limited connection to the substance. On the other end are visuals that present content connected to the facts or law.[3] Nix purely decorative visuals; visuals that contribute to the substance go in. I also recommend this article: Adam L. Rosman: Visualizing the Law: Using Charts, Diagrams, and Other Images to Improve Legal Briefs.[4]

Some simple examples of graphics

Last month I mentioned two reasons that some brief writers don’t use visuals: creating them can be difficult and time-consuming. So let’s start simple. Here are two ways to use one type of visual—images—in briefs, as recommended by respondents to my survey:

- I mostly use screenshots of the contractual or other language I’m interpreting.

- Many of mine are labeled photos—essentially, evidentiary documents but placed in the body text rather than in an appendix.

If using an image strengthens your case, do it.

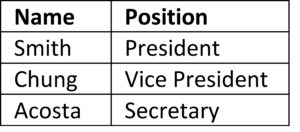

Using a table is another way to start trying visuals, and tables are simple to create.

For example, you might display the defendant’s corporate officers in a two-column table. The information is more quickly and easily grasped than if it were conveyed in textual format—especially if the list is long.

Text: The corporation’s officers were as follows: The president was Chris Smith, the Vice President was Cory Chung, and the Secretary was Jamie Acosta.

Visual: The corporation’s officers were as follows:

In an administrative-hearing brief, one writer needed to apply a 12-factor test to a nurse’s conduct. A two-column table worked well, with the factors described in the left-column cells and the analysis provided in the corresponding right-column cells. It’s a good example of a visual that makes digesting the analysis easier when compared to a traditional-text format.

The following table appeared in a response to a plaintiff’s motion to consolidate. It was the writer’s attempt to emphasize that although the same party owned the apartment-complex phases at issue, the buildings, subcontractors, and materials differed, and the two cases would not rely on the same evidence.

Once you’ve mastered basic tables, a timeline is a good challenge. Here’s a basic example:

I hope these examples give you some ideas. Ultimately, it’s up to you to consider the facts and analysis and decide if a visual is right for your brief. Think creatively, get some help, improve your skills, and recognize that judges are favorably disposed to visuals. Then try it.

_____

[1] Steve Johansen & Ruth Anne Robbins, Art-iculating the Analysis: Systemizing the Decision to Use Visuals as Legal Reasoning, 20 J. of the Leg. Writing Inst. 57 (2015)..

[2] Id. at 67.

[3] Id. at 69.

[4] Adam L. Rosman, Visualizing the Law: Using Charts, Diagrams, and Other Images to Improve Legal Briefs, 63 J. Leg. Educ. 70 (Aug. 2013).