BY RUIJIE PENG

Over the past decade, China and Latin America have experienced exponential growth in trade and direct investment. China is now the second largest source of imports and the second largest export destination for Latin American goods, behind only the United States in both trade and foreign direct investment (Chen and Pérez Ludeña 2013). Yet the numbers tell a limited story that gives insufficient attention to the experiences of human actors. As a master’s student at LLILAS, I became curious about the impact of Chinese foreign direct investments on people.

My Research

During my first semester at LLILAS, I developed a proposal to carry out research in two major areas to which Chinese investments flow in Latin America, the mining sector and the infrastructure construction sector. My previous research had identified the Peruvian mining sector as a prominent recipient of Chinese investment, while Chinese involvement in infrastructure construction is largely concentrated in Ecuador. In fact, although overall Chinese investment in Latin America is still in its initial stages, China has quickly become the largest source of foreign investment in Ecuador. I learned that a Chinese development bank had already provided a loan to the Ecuadorian government to finance what would be Ecuador’s largest hydroelectric power plant. Moreover, the plant is the first and largest project to be financed by a Chinese development bank and built by a Chinese construction firm, Chinese Hydroelectric Company (CHC).[1] I became interested in the growing economic and political ties between China and Ecuador as they are reflected in the construction of the project, and I decided to travel to Northern Ecuador for field research that summer.

During the preparatory phase of my research, I collected reports and investment statistics about the hydroelectric project. I quickly realized, however, that most of the information available on the Internet about the project was critical of its likely environmental impacts in Ecuador’s Northern Amazon. Additional searches turned up sporadic reports about Ecuadorian worker protests over the quality of the food and water at the project site.

Both the environmental impacts and workers’ rights protests caught my attention. As I read further into different reports, I noticed that while potential environmental impacts were contentious from the very beginning of the project, issues around labor rights seemed to be evolving as the project went on, especially considering that CHC is still adapting to operations in Ecuador. Unable to find more meaningful information on the Internet, even with powerful search engines, I planned a visit to the project site prior to carrying out my formal research in order to make contacts and obtain permission to conduct field research there. In December 2013, I flew to Ecuador for the first time and stayed for a month for my preliminary research.

My First Encounter with the Field Site

At first, I was only able to make contact with one Chinese person working in Quito, a UT alumnus employed by China’s development bank system there. He introduced me to a friend of his in a management position at CHC and I quickly realized that the Chinese expatriate business circle in Quito is very small and everyone in it knows one another. I seized the opportunity and made an appointment with the manager to talk about my research plan. I nervously introduced myself as a student researcher wanting to learn about the project’s operation and people’s experiences there for my thesis. The young manager was very open-minded and supportive. Unexpectedly, I was granted access to visit the project site for a week.

On that first visit, I took a four-hour car ride from Quito to the project camp 200 kilometers to the east, where many rivers pour a deluge of water down the flank of the Andes Mountains into the Amazon basin. As we neared the camp entrance, the driver carefully turned right into a paved road that led to a metal gate guarded by men in black suits, who sat in a booth. The gate was barely recognizable if one did not already know that it opened onto a construction camp. To the right side of the paved road, there is a large poster announcing the hydroelectric project that CHC is constructing. To the left of the gate, a brown stone pedestal with curved Chinese characters spells the name of the company. The driver pulled over as a security guard approached the car, writing pad in hand. The driver rolled down the window, handing his ID card to the guard, who jotted down the number on a sign-in sheet. The guard then looked around inside the car, glancing at each passenger while making eye contact. Drawing back his suspicious and inquisitive look, he waved his hand to let us in.

Entering the camp, we encountered long and winding green metal fences that encircled a group of buildings, clearly marking the boundary with the outside. At first glance, I caught sight of a giant, factory-like building with a blue rooftop, machinery, and big trucks. I heard the clanking noise of metal and the sound of machines running as we drove along the path. This is the mechanical workshop where custom-fitted construction parts are made. As we proceeded, we encountered another gate guarded by more men in the same uniforms, employees of a private security company. After the guards allowed us to pass this gate, I saw what formed a sharp contrast to the disorderly and informal look of the factories near the camp entrance: work facilities and accommodations were beautifully laid out. At that moment, I realized we were officially in the camp.

On the left side of the driveway there was a semi-oval parking lot with buses and several cars. On the other side, a beige concrete structure with blue metal rooftops served as the office building. There was a lot of buzz in this area from new personnel check-ins and material arrivals in front the office. This part of the camp, and particularly this office building, is where most of my work unfolded in the summer of 2014.

Uncovering a Different Story

This first visit to the field site substantiated and transformed my research interests and my sense of purpose. Before going there, my initial and broad interest was to look at performances and impacts of Chinese investments on a human level. I had read volumes of papers and essays about the development of Sino–Latin American relations and seen figures from the recent period of vibrant trade exchange and foreign direct investment between the two regions. However, being on the ground in an actual project site was a strong reminder that researchers and scholars have not had access to evaluate the human impacts and interactions of a Chinese construction project, especially one in which people of different nationalities and cultures converge and work together.

Although I only stayed in the field for a brief observation period during my first visit, I quickly developed a trusting relationship with the young Chinese engineers and interpreters of my age group. The more I got to know individuals who work on the project, the stronger became my desire to investigate their work experiences there. There is a popular perception that Chinese modernization projects operate similarly to earlier capitalist projects, controlling local resources and population. For example, the sparse reports I was able to find online record Ecuadorian workers’ grievances over food quality. However, my stay and close interaction with Chinese staff and workers on the site gave me the impression that this project, including its problems, has characteristics that are distinct from previous such projects. My initial visit exposed to me a more complicated and counterintuitive side of the story about workers’ treatment and the labor rights provisions of Chinese nationals in the project. While it is true that the Chinese expatriate workers and staff, who number close to 1,300 people, receive significantly higher salaries than workers in China, they do not enjoy the same labor rights as their Ecuadorian counterparts on the project. In fact, many Chinese engineers confided that they feel as thought they are working in a prison because all of their work and their lives revolve around the project and its progress. By the end of my first visit to the field site, my intention to look at human interactions had further materialized into an investigation of reasons that contribute to differential work treatment, labor rights provisions, and the disparate workplace experiences of Chinese and Ecuadorians.

The Challenge of Starting Field Work

In the summer of 2014, with the intention of documenting Chinese and Ecuadorian workers’ experiences with the workplace and with each other, I returned to the field with written interview scripts, a matrix of employee categories, and numbers of interviews that I wanted to conduct during my fieldwork. Although almost everybody in the office knew I was a student carrying out research for my thesis, people tended to regard me as a new interpreter doing an internship with the company in our interactions. During the entire process of my fieldwork, I stayed in the technical department’s office while people were working during the day.

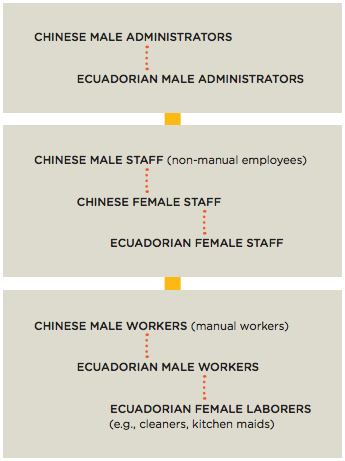

My first job was to understand the organization of people in the project. At the CHC site, male Chinese managers and engineers occupy most managerial positions, with the exception of two Ecuadorian heads of department. Chinese manual laborers, all of whom are certified skilled workers,[2] occupy leadership positions over lower-skilled Ecuadorians on their construction teams. No women work as either administrators or manual laborers. Chinese women, about 2 percent of the entire workforce, work as interpreters, accountants, and heavy machine technicians. Local Ecuadorian women largely work as maintenance staff on the lowest rung of the hierarchy. Figure 1 roughly represents the schematic job distribution.

My second task was to immerse myself in the daily rhythm of work at the project. Many of my informants reported the normal workday as being repetitive and monotonous. All employees observe a strict work schedule. People go to the canteen for breakfast between 6 and 8 a.m. and start work at 8. They have a two-hour lunch break between noon and 2 p.m. before resuming work until 6 p.m. Since the office has such a strict atmosphere, I took advantage of my time there to observe how people work individually, with other people and parties, or during negotiations at meetings. Apart from participant observation, I carried out interviews after formal working hours, usually at night in the office building, where most people chose to spend their time. My informants included people who work at all levels in the job distribution shown in Figure 1. Before I began the interviews, I designed a series of questions on topics ranging from daily work routines to employees’ feelings about working conditions, experiences communicating with co-workers, and the ways in which they settle complaints and grievances with the company. I then started to make interview appointments with people I already knew and to whom I had easier access.

In the beginning, my informants and I were nervous and tense because I was going through a rather rigid list of questions and their trust in me was yet not fully established. I remember talking with an Ecuadorian worker who felt some bitterness about his treatment. When it came to answering my question about the ways in which he went about resolving these grievances, he suddenly became very mechanical and answered in a politically correct way: he said he only went to the human resources office with complaints and waited for responses. He avoided talking about the small labor unions that existed among the workers and other informal modes of protest at workplace, of which I only became aware later on. The same thing happened with Chinese informants. It was hard to get them to talk about their true feelings toward the project, especially their negative experiences. The largest problem was always trust. They assumed that I would communicate their negative comments to the company, which could get them in trouble.

As time passed and mutual trust was built, the Chinese informants who were closer to me often asked me to turn off the recorder so that they could talk about their past protests and attempts to negotiate their treatment with the company. Indeed, many of the moments of disclosure took place off the record. People would share feelings about working on this remote project where their personal and financial freedom were largely restricted despite the fact that they could earn good money. They talked about how difficult it was to communicate with Chinese bosses or Ecuadorian workers while working side by side at the construction site. They also told me of their struggles to maintain relationships with significant others or family while working afar.

Being immersed in the field allowed me to fully use my intuition and capture assorted details. After almost three months in Ecuador, various kinds of information seemed to congregate in my mind, each piece representing part of a larger mosaic that needed to be assembled. But while I was in the field, I was unable to take a step back to see the entire picture. Only after leaving the field was I able to reflect and begin to process the huge amount of information I had recorded, allowing me to identify recurring themes that would gradually grow into the pillars of my thesis. These themes include labor control through division, perceptions of rights among different subjects, and gender.

Initial Research Findings

Labor Control Through Division

Entering the project camp day after day, I began to feel the tight control the company imposes on physical boundaries as well as on people’s movements in the space. The assignments of office space, canteens, and dormitories all follow an obscure underlying principle. The more I observed both the physical layout and the organization of personnel, the more I understood the employer’s intention of differentiating the population according to nationality, professional rank, and gender. I was able to observe how the company’s spatial practices influence the ways in which employees behave in the spaces. For example, the crowded male barracks and the more spacious senior apartments discourage association and communication among people who rank differently in the professional hierarchy.

Meanwhile, the organization of personnel is also highly divided according to nationality. Chinese men dominate the management and technical levels. On the workers’ level, Chinese manual laborers supervise a much larger population of Ecuadorian manual laborers at the actual construction site. I initially got the sense that this was because Chinese migrant workers in Ecuador are more technically adroit in their skills, whereas many Ecuadorian workers have little training, having only shifted from subsistence farming or other informal occupations to become contract workers. However, after reviewing more literature on work control while crafting my thesis, I gradually came to grasp a more complicated reality: both the spatial and the organizational practices at the site contain principles for division that in effect constitute a form of social control that differentially disciplines staff and workers.

Perceptions of Rights Among Workers

As the construction project brings 20 percent of its labor from China, male Chinese manual laborers have become the largest economic migrant population to participate in Ecuador’s new trend of economic globalization. In this new space, Chinese and Ecuadorian laborers work together, and while Chinese capital and the Chinese construction company may mean the domination of Chinese personnel in the project, I found the Chinese migrant laborers to be locked in the same predicament that has always confronted migrant workers. Typically, workers laboring in foreign lands are paid lower wages than their local counterparts and experience more powerlessness in negotiations for better treatment (Sassen 1990). In the case of the Chinese employees, these conditions strangely replicate themselves even though it is Chinese transnational capital that operates the project. The wages of the Chinese workers are lower than those of Ecuadorian personnel with the same qualifications. In addition, the Chinese workers have less leverage to negotiate for better work treatment than either Ecuadorians or Chinese workers employed domestically in China. However, in terms of salary and professional status, working abroad has afforded these Chinese migrants the chance to earn considerably higher wages and elevated job status compared to working inside China. Thus, Chinese employees’ transnational movement to Ecuador and their work in an international setting produces a set of complex conditions that influence the production of social relations—that is, how they relate to co-workers of a different nationality and to their superiors at work, based on how much power they believe themselves to possess. With such contrasting perceptions of rights between Chinese and Ecuadorian workers, I further explore in my thesis how and why Chinese workers are made to take and stay in certain job positions in the process of labor division.

Gender

Before entering the field, I never imagined that gender would be such an important dimension of my research experience. Yet the moment I saw the green fence around the female staff dormitory, setting that space and its occupants apart from other residents of the camp, I began to consider the importance of this lens in my understanding of the project.

Of the twenty barrack dormitory units for manual workers and entry-level staff, only two house Chinese female staff, as well as a small number of Ecuadorian women from distant provinces. The Chinese construction company explained that the fence segregating the women’s dormitories was built to protect women from male harassment, yet female workers living inside the fence appeared to feel more restricted than protected by it. In fact, the presence of the fence caused many women to be highly sensitive about whether or not their female colleagues were inside the fence at the right time, especially at night. Women living inside the camp gossiped among themselves about other women who did not observe the curfews and schedules. This talk often eventually spread outside the fence. Among Chinese women in particular, I found that instead of being a source of care and protection, the fence functioned as a pressure seeking to discipline their behavior and their social interactions according to Chinese patriarchal standards and criteria for women’s comportment.

My observations and interviews helped me identify revealing patterns in discourses and practices surrounding female workers. I found that patriarchal and gender-based characteristics of capital operations in general, and the distinct cultural features of Chinese modernization projects in Ecuador in particular, underlie the patterns of interaction that women experience in the project. By exploring the influence of the fence on women’s perceptions and experiences, I sought to explain the gendered aspects of their interactions with the company and with one another. In my thesis, I posit that the fence, as part of the objective realities women face, can shed light on the cultural politics of labor control.

Difficulties and Triumphs

With these recurring themes in mind, I returned from the field at the end of the summer with loads of field notes, interviews, memories, and feelings gathered while working in Ecuador. Toward the end of my stay in the field, I was approached by the manager who had introduced me to the site. He asked me whether I had gathered enough data for my thesis, politely hinting that it might be a good time to leave the field.

At that moment, I reflected upon my own social positions and privileges, which had granted me access to the site, as well as my own perspectives and biases. As a Chinese national, I was able to gain access to a highly restricted field site because of my personal networks and the trust bestowed upon me based solely on my nationality and skin color. As a woman, I developed close ties with some female employees on the site who allowed me a glimpse into their lives. They treated me as a good friend. Sitting in front of the computer and writing my thesis, I once again feel very lucky to have virtually stumbled upon access to the field site, which might have been completely elusive to me—part of the unpredictability factor for all field workers. At the same time, I am exploring the best way to interpret, respond to, and connect the stories, trust, doubts, and friendships that I encountered in the field so as to shape them into a meaningful mosaic that tells a story.

Just as Aihwa Ong (2010) declares when reflecting on her writing about Malaysian female factory workers, I do not aspire to “represent” the meanings my informants make about their lives, nor do I claim to fully understand the scope of the complicated capital operations and social relations. Writing the above account, I came to see my work as an effort to piece together different facets of social life into a cohesive whole while cognizant of how impossible it is to achieve a coherent and refined vision of the social reality and the impacts Chinese of transnational modernization projects at the human level.

In my thesis, I have attempted to tell a story about the ways in which Chinese transnational modernization projects operate in Ecuador, emphasizing impacts on the human actors and their social relations. Now, the more I revisit the field through my notes, memoirs, and interviews, the more I realize I am just beginning to learn about the labor issues emerging from economic and social development both at home and abroad.

Ruijie Peng is a 2015 graduate of the LLILAS MA program. She conducted her field research in the Northern Amazon region of Ecuador during the summer of 2014. She entered the sociology PhD program at The University of Texas at Austin in fall 2015. This article was originally published in the 2014–2015 edition of Portal.

Notes

[1] The company name, as well as names of the project and project site, are fictitious due to the company’s concerns for privacy and to protect the informants’ identities.

[2] Chinese manual laborers are selected to work overseas based on their qualifications. They must have professional certification and considerable work experience to qualify for work abroad. In contrast, most Ecuadorian workers come from rural backgrounds without the specific skills the project requires.

References

Chen, Taotao, and Miguel Pérez Ludeña. 2013. Chinese Foreign Direct Investment in Latin America and the Caribbean: China–Latin America Cross-Council Taskforce. Working document. Abu Dhabi: World Economic Forum (WEF).

Ong, Aihwa. 2010. Spirits of Resistance and Capitalist Discipline: Factory Women in Malaysia. Albany: SUNY Press. Sassen, Saskia. 1990. The Mobility of Labor and Capital: A Study in International Investment and Labor Flow. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.