BY THERESA E. POLK

Guatemala’s internal armed conflict was brutal by all accounts, and justice for human rights violations has been notoriously difficult to attain in its wake. Yet there have also been some critical milestones, including convictions in 2010 for the forced disappearance of labor and student leader Edgar Fernando García, in 2011 for the massacre at Dos Erres, and earlier this year for sexual slavery in the Sepur Zarco trial.* Archival documents have played an often quiet but critical role, as background research in preparation for trial and evidence in the courtroom, as a source of information for families of victims, and as critical threads in the construction of narratives about the recent past. Yet, despite this critical role, archives, and particularly human rights documentation, remain vulnerable due to lack of infrastructure, as well as political threat.

Traditional acquisitions practices have been based on taking physical custody of archival collections in order to preserve and provide access to them, yet this is a problematic solution for human rights documentation. Record holders are reluctant to relinquish custody of their materials, even temporarily. In fact, removing archival records can be disruptive to immediate programming and operational needs, let alone larger societal processes concerning transition, recuperation of historic memory, and reconciliation. At the same time, given historical relations and imbalances of power between the U.S. and Latin America, and the perceived plundering of cultural patrimony and appropriation of cultural heritage, archival institutions are understandably reluctant to hand their records over to a large U.S. institution.

These considerations are particularly sensitive in the case of human rights documentation. For instance, records such as those contained in the Guatemalan National Police Historical Archive (AHPN) are the product of a massive state surveillance apparatus turned against its own citizens. On the one hand, such records can support struggles for justice and the full realization of rights, but on the other they can also feed the mechanisms of state repression. Our archival partners are justly careful about what information they are willing to share, with what potential audiences, and via what means of distribution.

As an alternative, over the last two years, LLILAS Benson, through a pilot project funded by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, has been working to develop a different approach to preserving and providing access to vulnerable human rights documentation in the Latin America region based in post-custodial archival theory. Rather than physically taking custody of partners’ collections, project staff from the Benson Latin American Collection provided consultation, digitization equipment, and archival training in preservation, arrangement, description, and digitization of vulnerable archives. Partner institutions prioritized the collections to be included in the project, conducted the digitization work, and provided descriptive information about the materials. This approach allowed our partners to retain both physical and intellectual control over their collections.

We also explicitly adopted an emphasis on human rights, with race, ethnicity, and social exclusion as a lens for our work. This refocused our attention on communities marginalized not only in social, political, and economic processes, but also in the historical record. Indigenous and African diasporic communities and organizations are the most underrepresented in cultural heritage institutions at local, national, and international levels, and when they are portrayed, it is even more rarely with their input or consent. A post-custodial model offers these communities and organizations greater control over selection, description, and access to their documentation, and helps build local capacity to preserve vulnerable collections.

In close consultation with scholars at The University of Texas at Austin, three archives were selected for the initial phase of the project: the Centro de Investigación y Documentación de la Costa Atlántica—CIDCA in Bluefields, Nicaragua; the Centro de Investigaciones Regionales de Mesoamérica—CIRMA in Antigua, Guatemala; and the Museo de la Palabra y la Imagen—MUPI in San Salvador, El Salvador. Project staff from UT sourced appropriate digitization equipment and conducted training locally onsite, working with our partners to develop workflows that made sense for them.

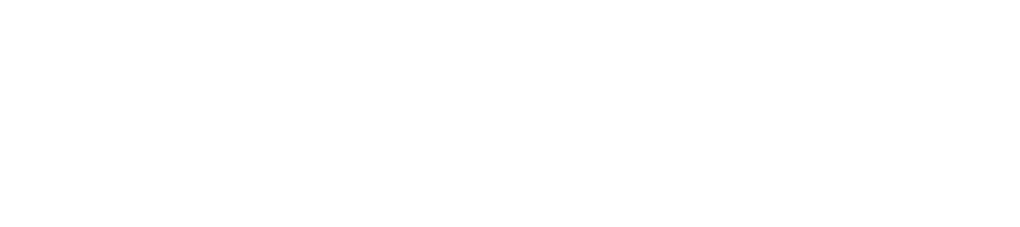

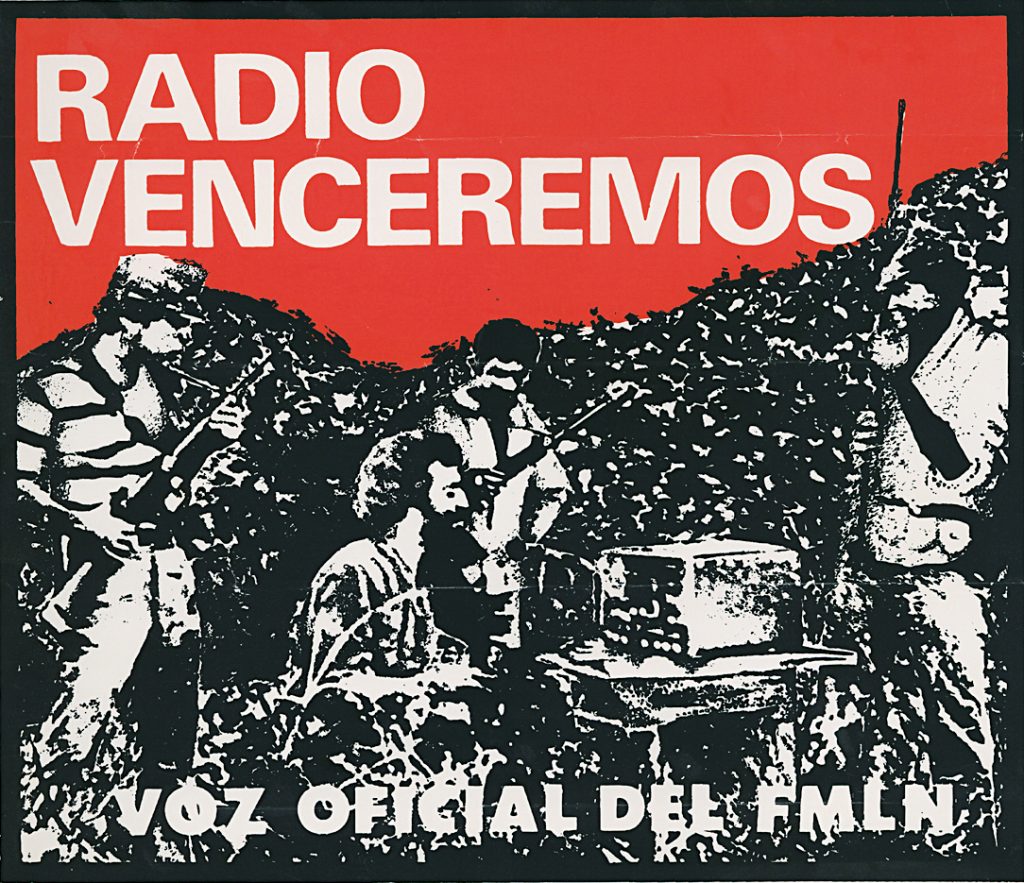

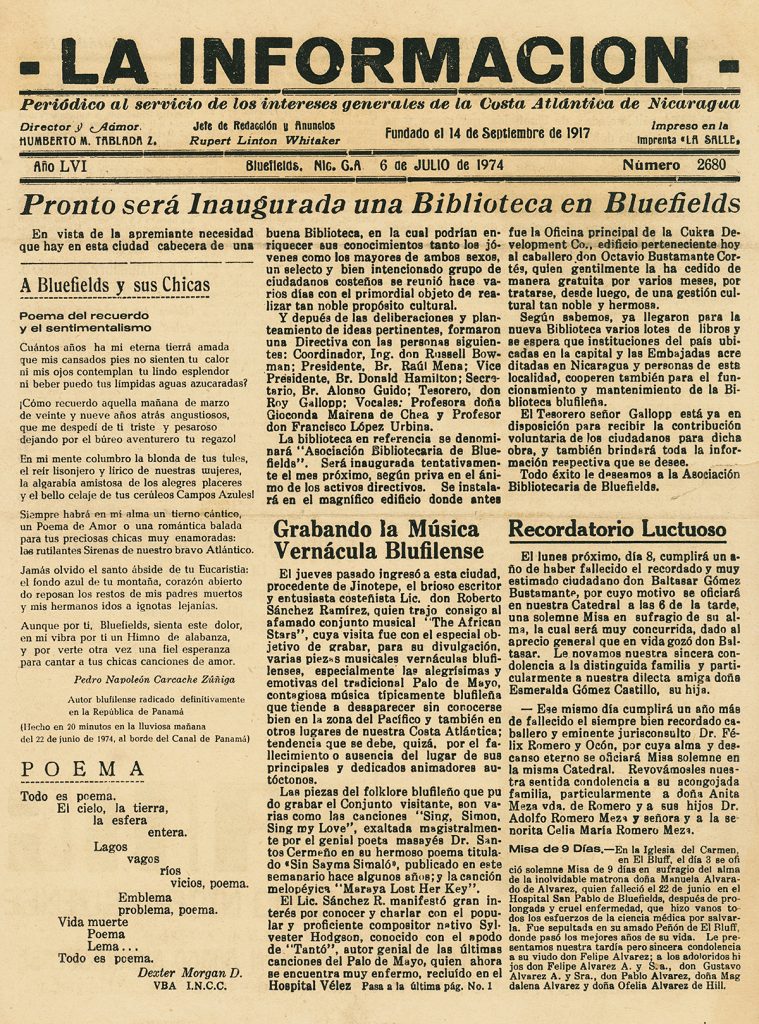

The collections were chosen based on the convergence of collection priorities articulated by our partners, input from scholars with an expertise in contemporary Central America, and LLILAS Benson’s interest in collections documenting human rights. CIDCA digitized an estimated 900 issues (1920–1998) of La Información, a local newspaper that covered the economic, social, and political life of Nicaragua’s Atlantic Coast, offering a unique historical window to the lives and experiences of indigenous and Afro-descendant communities. CIRMA digitized approximately 4,700 news clippings from the Inforpress Centroamericana archive that capture how violence and repression transformed and intensified during the height of Guatemala’s internal armed conflict. MUPI digitized its holdings of clandestine publications of the Salvadoran civil war, portraying voices and experiences from the frontlines of the conflict from 1979 to 1992, as well as a closely related, visually compelling collection of solidarity and propaganda political posters.

The collections complement each other, and existing holdings and research strengths at LLILAS Benson, opening exciting new avenues for scholarship. Articles in La Información offer a Nicaraguan perspective on Guatemala’s 1954 coup. The Salvadoran and Guatemalan collections provide a glimpse into how both repression and resistance were internationalized during the height of the Central American conflicts by documenting the movement of key actors between the countries. MUPI’s posters present an engaging complement to the Benson’s previously digitized recordings of Radio Venceremos, clandestine radio broadcasts from the Salvadoran conflict. And we have started to identify connections between Inforpress news clippings and records in the digital AHPN.

An online repository—Latin American Digital Initiatives (LADI, at ladi.lib.utexas.edu)—was created in collaboration with the University of Texas Libraries to provide access to the digitized collections, utilizing the open source Fedora/Islandora repository framework. For UT Libraries, the project served as a test case for in-house development with Islandora, helping to identify requirements for bringing additional UT collections online. The site was jointly launched during a powerful symposium in November 2015, which brought together the technical staff who had created LADI with scholars from the UT community, representatives from each of the participating archives, and potential future project partners. Together, we had a rich conversation not only about the content, but also about the skills and technology necessary to provide online access to that content, making visible the often hidden back-end work involved.

Overall, the project laid a strong foundation for the institutionalization of post-custodial archival practice at LLILAS Benson, and opened exciting new opportunities for collaboration to preserve vulnerable human rights documentation in the Latin American region. It has also created new opportunities for research and teaching on the UT campus. During the spring semester of 2016, history professor and incoming LLILAS Benson director Dr. Virginia Garrard-Burnett, with the support of project staff, taught a graduate history seminar based on the LADI collections. The course integrated traditional modes of research along with digital scholarship methodologies for critically interacting with, interpreting, and contextualizing the digital collections. As we look to the future of post-custodial archiving at LLILAS Benson, we embrace the hope of building strong, multifaceted relationships with our partner organizations, and with the scholarly community on campus that will nourish this vibrant initiative.

Theresa E. Polk is the post-custodial archivist at LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections at The University of Texas at Austin. She has a BA in Latin American studies, and master’s degrees in library science and international peace studies. Prior to becoming an archivist, she worked on international human rights and development policy.

*To learn more about the Sepur Zarco war crimes trial, see Struggles and Obstacles in Indigenous Women’s Fight for Justice, in this issue.