BY AÍDA HERNÁNDEZ CASTILLO

Mexico is engulfed in a human rights crisis. The current atmosphere of violence and impunity implies new challenges for social anthropology and, more specifically, legal anthropology. Long-term fieldwork in regions affected by violence involves multiple risks for researchers and students. This forces us to seek collective research strategies with interdisciplinary teams, in collaboration with civil society organizations. This article shares some of the challenges and achievements in the Mexican context, as we attempt to develop socially committed research practices amid multiple types of violence.

Legal Activism in the Face of Injustice

Over the last ten years, the so-called War on Drugs in Mexico has resulted in 100,000 dead and 30,000 disappeared, hundreds of clandestine mass graves throughout the country, and thousands of people internally displaced. Practitioners of legal anthropology have placed our hopes in legal activism based on collaborative research, such as the use of anthropological research for the co-production of knowledge that can be used in the legal defense of the people with whom we work. Yet we face a reality of impunity, where state justice is entirely delegitimized, making it almost impossible to consider an “emancipatory use of the law.”1

During the last 25 years, my academic work has revolved around a feminist legal anthropology based on collaborative methodologies linked to legal activism. While engaging in continuous critical reflection on the law and rights, I have taken part in initiatives to support indigenous peoples and organizations who use national and international legislation in their struggles for justice. From this critical standpoint, I helped to write anthropological expert witness reports that have aided in the defense of indigenous women in national and international legal cases. (See my book Multiple InJustices: Indigenous Women, Law and Political Struggle, University of Arizona Press, 2016.)

But the “emancipatory” use of the law seems to be reaching its limits where organized crime operates from within the state’s institutions themselves. The problem in certain regions of Mexico is not only impunity and the inefficiency of the security and justice system, but the fact that violence emanates from the very institutions that should protect us. The murder of six people and the forced disappearance of 43 students from the Raúl Isidro Burgos teacher training college of Ayotzinapa, Guerrero, on September 26 and 27, 2014, was a watershed moment in relations between civil society and the Mexican state. The fact that the students were kidnapped by municipal police officers and handed over to members of the criminal organization Guerreros Unidos demonstrated what was already an open secret: organized crime operates from within the state itself.2

The search for the 43 students mobilized not just their families and human rights organizations, but the entire country. Thousands of people took to the streets with the slogan “Fue el Estado” (“The state did it”). In response to the hypothesis that the students were murdered and incinerated in a trash dump, a search for human remains began that, while failing to locate the 43, led to the discovery of more than 150 bodies buried in clandestine mass graves. This unleashed an unprecedented national process: throughout the country, the relatives of the disappeared grabbed picks and shovels and took to the task of searching for their sons and daughters. Without losing hope of finding them alive, but acknowledging the real possibility that they were dead, family members began searching in empty lots, in trash dumps, around rivers, and on the margins of irrigation canals. Search collectives were created in Guerrero, Veracruz, Sinaloa, Nuevo León, Chihuahua, and Coahuila, which later joined forces as the National Brigade for the Search for Disappeared People.

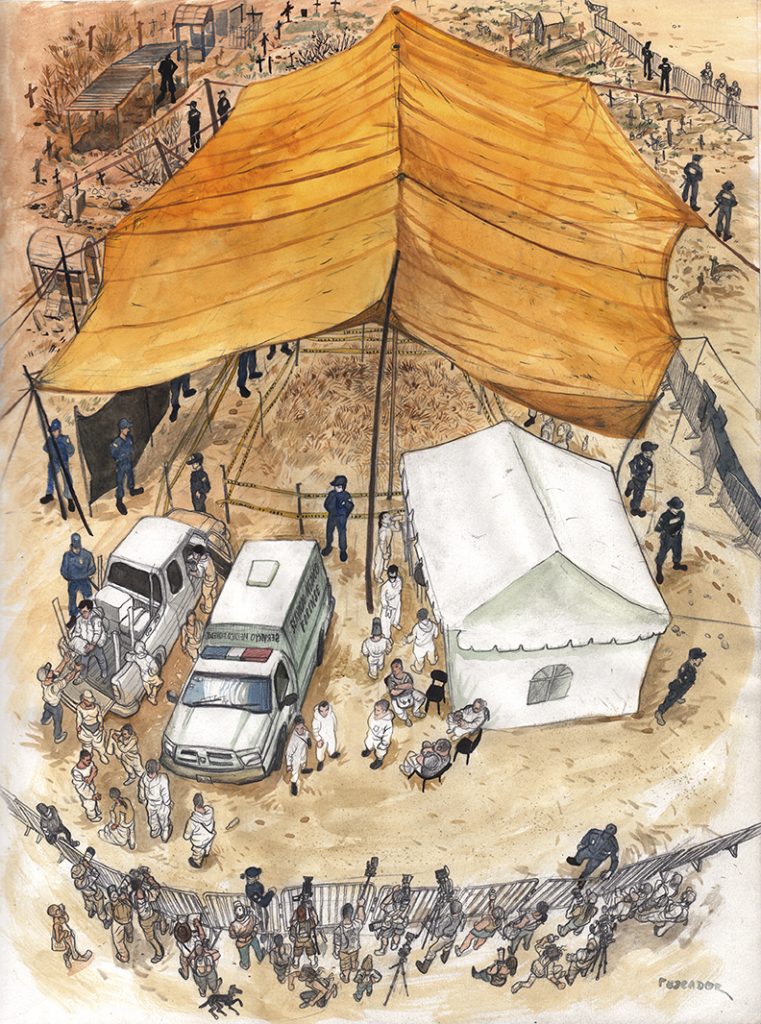

Mass Graves and Forensic Anthropology

The sight of horror became an everyday fact: families began to find mass graves almost daily and they began to conduct the sorts of investigations that the government had been unable or unwilling to undertake. As a result, the relatives of the disappeared have become self-taught forensic researchers, learning a new, specialized language of genetic tests, DNA, exhumations, antemortem, postmortem, and so forth. Each organization has created its own database with names, ages, locations of disappearance, clothes worn, and other details.

But the families have not been alone in these searches. A young generation of archaeologists and physical anthropologists specialized in Mesoamerican cultures, together with social anthropologists, decided to aid in the search for the disappeared. As was the case with the creation of the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF) in 1984 or the Guatemalan Forensic Anthropology Foundation (FAFG) in 1997, the need for independent experts to witness and advise during searches for the disappeared led a generation of Mexican anthropologists to engage in forensic sciences. Since 2013, a group of anthropologists, mostly young women, has come together as the Mexican Forensic Anthropology Team (EMAF), which began developing independent expert reports for paradigmatic cases, but which, with the creation of the search brigades, also started offering training workshops and observing exhumation processes at mass graves upon request of the relatives.3

Legal anthropologists like myself, who work on topics related to legal pluralism or indigenous rights, have been forced to delve into disciplines that bring us close to what Spanish anthropologist Francisco Ferrándiz has termed “ethnography by the mass grave.”4 Wishing to use my legal activism experience to contribute toward the search for justice, I joined the Social and Forensic Anthropology Research Group (GIASF) at the invitation of my colleague Carolina Robledo Silvestre. The group includes a physical anthropologist, an archaeologist, a lawyer, and three social anthropologists. We are advised by a group of experts from areas such as geophysics, social psychology, and criminalistics, among others.5

With the institutional support of CIESAS (the Center for Research and Advanced Study in Social Anthropology), albeit on a tight budget, the members of GIASF have traveled in the last year to the states of Veracruz, Coahuila, Baja California, Sinaloa, Chihuahua, Morelos, and Nuevo León, providing training and technical and legal advice to collectives of families of disappeared people on topics related to the search for and exhumation of human remains. In addition to offering workshops, GIASF has been present at exhumations of mass graves in Coahuila and Morelos, and its members co-authored a report on the case of the mass graves in Tetelcingo, Morelos.6 Yet the extreme violence, impunity, and complicity between security forces and organized crime have made it almost impossible for us to accompany judicial processes in the same way we had for our anthropological expert witness work at CIESAS.7

For many relatives of disappeared people, demanding punishment for the guilty implies putting oneself at risk and, more significantly, putting other sons and daughters at risk. This reality is illustrated in a slogan adopted by some of the family organizations: “We don’t want justice, we want truth.” Anthropologists’ experiences in legal activism are of little use when the priority of families is to find their children, to give a face and a name to the disappeared, and to end the cycle of mourning by burying their loved ones with dignity. To understand these processes, it has been necessary to recognize the meaning underlying the search for justice from below, prioritizing the demands and practices of the mothers and fathers of the disappeared without imposing upon them our own pre-established categories regarding justice and reparations.

Methodological Challenges in Contexts of Violence

In contrast with the experiences of forensic anthropologists in the Southern Cone, Peru, or Guatemala, we are not operating in a context of post-internal conflict, or what has been called “transitional justice.” In Mexico, we are in the midst of an internal war that has not been recognized, and in which the perpetrators of violence could be members of organized crime or of the government in power. This has forced us to develop different strategies to reconstruct the “forensic context,” to avoid risking the safety of our team and of the families with whom we work. Links with international organizations like the Red Cross and the United Nations Human Rights High Commissioner (OHCHR) have been fundamental in the development of a safety protocol. Through an initiative promoted by the OHCHR, we joined with other forensic teams that work in Mexico to found the Forensic Space for Human Rights, a network to articulate our efforts and discuss our methodological challenges.

In the context of multiple types of violence, we believe that social anthropologists can play an important role in forensic teams, expanding how the “forensic context” is conceived. This includes acknowledging the socio-historical origins of violence and understanding the body not only as a biological entity, but in its symbolic and cultural dimensions (see the work of Elsa Blair).8 As legal anthropologists, we must expand our conceptions of legality and learn from the knowledge and experiences of the relatives of the disappeared, whose conceptions of justice and reparation do not always proceed along the path of state law. We must thus put aside our belief in the importance of our own point of view and open ourselves to other understandings of restorative justice in order to place our knowledge and skills at the service of family organizations.

Our analyses of legal processes and ethnographies of state spaces can help document how “state bureaucracy” is re-victimizing relatives of the disappeared. From the moment a family formally reports a disappearance, a “bureaucratic via crucis” begins, with documentation, procedures, and other tasks that often continue for years without leading to progress in the investigation. When searches are fruitful, the bureaucratic labyrinth continues in order to make sure that the human remains are identified and the bodies turned over to the relatives. Waiting months for DNA test results becomes a form of torture in and of itself.

On the other hand, our anthropological expert witness work has allowed us to analyze to what extent the ethnic/racial, gender, and class exclusions that mark the lives of the mothers of the disappeared have aggravated the conditions of vulnerability in which they undertake searches and confront state institutions. This has meant participating in workshops with members of mothers’ organizations to examine how they imagine and experience justice, beyond the accepted frameworks and procedures.

The life histories methodology I used in my previous research with indigenous women in prison9 has helped to reconstruct the accumulation of vulnerabilities that mark the lives of those women and their disappeared sons and daughters. At the level of forensic anthropology, these life histories can be used to develop the “antemortem records” that provide the context of the disappearance and lead to future identification of the human remains. Likewise, our ability to analyze the contexts in which forced disappearance takes place allows us to reconstruct the multiple vulnerabilities and status of impunity that make forced disappearance possible. In the long term, we believe that our interdisciplinary research can help to identify patterns of forced disappearance that contribute toward prevention and, in the future, toward the search for justice.

Crucial Work with Limited State Support

Efforts to place scientific research at the service of civil society are being undertaken with increasingly scant state support for science and education in Mexico. So, even as spaces to produce “science with consciousness” are created, the national budget for science and technology was cut by 7 billion pesos in 2017, leaving resources at 23.3 percent less than the previous year. Alliances between researchers and relatives of the disappeared face further challenges. Lacking funds for fieldwork, laboratories, or technical equipment, Mexican researchers are forced to use their meager salaries to respond to this national emergency.

We are still at the beginning of a long road to build alliances between legal and forensic anthropology in Mexico. It is my hope that someday the research that is now beginning can contribute to finding truth and justice, and put an end to the violence and impunity that threaten our children’s future.

Aída Hernández Castillo is a Mexican anthropologist. She was Tinker Visiting Professor at the Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies during fall 2016. She is a senior researcher-professor at CIESAS México, and a member of the Social and Forensic Anthropology Research Group (GIASF).

This article was translated from the Spanish by Alejandro Reyes.

Notes

1. Boaventura de Sousa Santos, “¿Puede el derecho ser emancipatorio?” Derecho y emancipación, 63–146 (Quito: Corte Constitucional para el Período de Transición and Centro de Estudios y Difusión del Derecho Constitucional, CEDEC, 2012).

2. See Hernández Castillo and Mora, “Ayotzinapa: ¿Fue el Estado? Reflexiones desde la antropología política in Guerrero,” LASAFORUM 46, no. 1 (2015): 28.

3. See Equipo Mexicano de Antropología Forense, “¿Quiénes somos?”

4. See “Entre víctimas: investigando las exhumaciones de las fosas comunes de la Guerra Civil en la España contemporánea,” May 18, 2017.

5. Learn more at www.giasf.org.

6. See “Fosas clandestinas de Tetelcingo: Interpretaciones preliminares,” special issue, Resiliencia no. 3 (July–September 2016).

7. See Rosalva Aída Hernández, “CIESAS,” at www.rosalvaaidahernandez.com.

8. See the work of Elsa Blair, Muertes violentas: La teatralización del exceso (Medellín, Colombia: Editorial Universidad de Antioquia, 2005).

9. See Rosalva Aída Hernández, “Colectiva Editorial Hermanas en la Sombra.”