BY HANNAH ALPERT-ABRAMS AND MARIA VICTORIA FERNANDEZ

In 1595, in Mexico City, the Jesuit priest Antonio del Rincón (1555–1601) published a grammatical description of the Nahuatl language. Though other grammars of Nahuatl existed, Rincón’s Arte mexicana was the first to describe the indigenous Mesoamerican language from the perspective of a native speaker, and the first written by someone of indigenous descent. It has been argued that Rincón’s ability to recognize many unique qualities of the Nahuatl language was the product of both his indigenous and European training.

Just over four hundred years later, Rincón’s Arte mexicana has been published again. It is one of several hundred books in the Primeros Libros de las Américas collection, a repository of books printed in the Americas prior to 1601. Much like the original volume, which was printed by Pedro Balli just a few decades after the first printing press was established in the Americas, this new edition brings together indigenous language, Western intellectual traditions, and experimental technologies for book production.

Only this time, the technology is digital, and the book is being written by a machine.

The “Reading the First Books” project is a collaboration between LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections at The University of Texas at Austin and the Institute for Digital Humanities, Media, and Culture (IDHMC) at Texas A&M University to develop technologies for the digitization of early colonial printed books. The project focuses on the books in the Primeros Libros collection, which was founded by a group of universities (including UT Austin) in 2010.

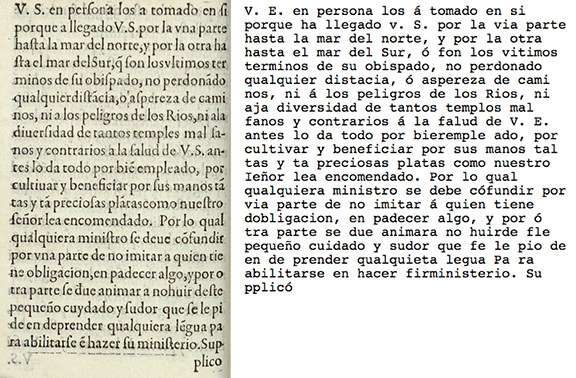

The original goal of Primeros Libros was to produce digital facsimiles: photographs of historical books that could be easily browsed online. But it soon became clear that pictures of the books weren’t sufficient. People wanted to be able to use a search engine to explore the collection, and to analyze the text using computational tools. In order for researchers to directly interact with the text, the books had to be transcribed. But with almost 50,000 pages of text (and counting), typing up the books by hand would have been an insurmountable task.

That’s where “Reading the First Books” came in. In 2015, a team of faculty, students, and librarians set out to identify tools that could automatically transcribe books from early New Spain. What we found is that while many tools exist that can automatically transcribe printed text, none of them was well suited to the particular challenges of colonial books.

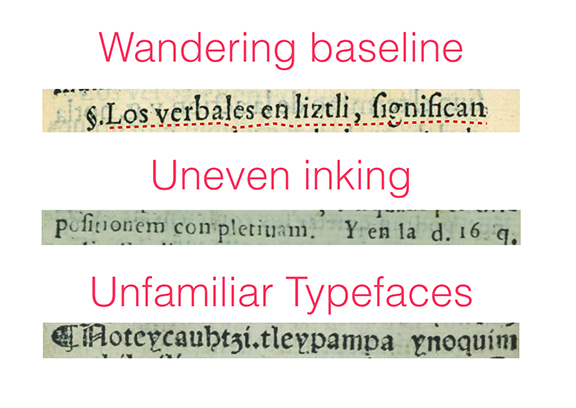

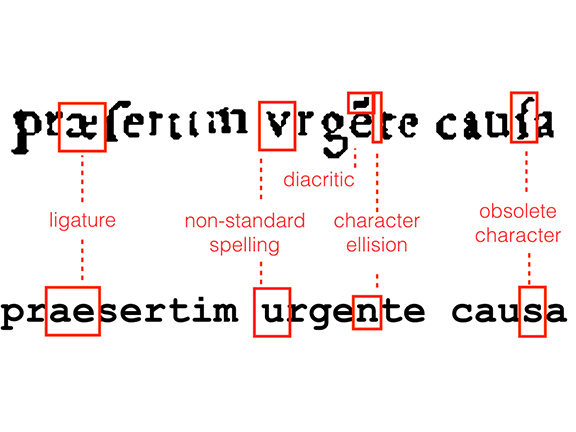

One reason that transcription tools struggled with the Primeros Libros has to do with the material qualities of these historical books. Books printed on a letterpress, like those from colonial Mexico, often use unfamiliar typefaces, including blackletter and italic fonts. The characters are aligned unevenly on the page, and are sometimes printed with too much or too little ink.

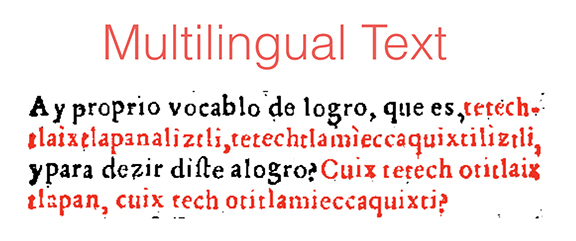

A second difficulty came from the way the colonial books were written. Spelling was less consistent during the early colonial period than it is today, as was the use of accents and other diacritics. Printers often used shorthand that can be hard to decipher, writing “˜Q” instead of “que,” for example. Finally, the documents in the Primeros Libros corpus frequently switch between multiple languages. In the case of a dictionary or grammar, multiple languages can even appear in a single sentence.

With the support of LLILAS Benson and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) Office of Digital Humanities, we set out to develop transcription tools that could handle the unique challenges of the Primeros Libros collection. We also worked with the IDHMC to develop an interface for transcribing and managing the data of a large corpus of books. We are currently working with the University of Texas Libraries to make these new transcriptions available on the Primeros Libros website.

New Texts, Old Books

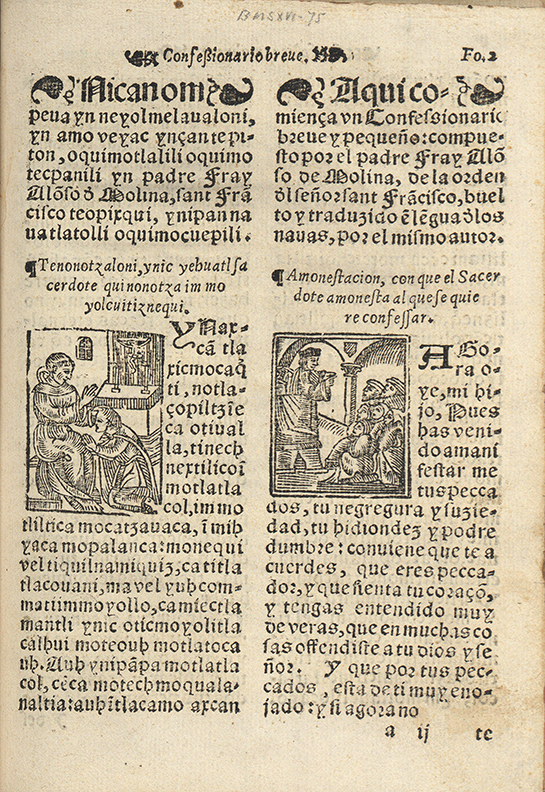

The books in the Primeros Libros collection cover a broad range of intellectual thought from early New Spain; topics include medicine, theology, evangelization, and linguistics. Many of these books were produced by Spanish mendicant friars, who followed on the heels of the explorers and conquerors of Mesoamerica. Among them were several missionaries who worked as linguists, adapting alphabetic script to capture and write in the indigenous languages they encountered.

Today, the work of these missionaries is remembered within the context of the Black Legend of Spanish conquest. But as linguistic anthropologist Joseph Errington writes, “They did not understand theirs to be the work of enslaving, murdering, or displacing the local indigenous populations; it was rather to make them Christians” (2008, 29). In order to spread the Catholic faith, missionaries learned indigenous languages and searched for a fit between these unfamiliar languages and their own categories of meaning.

Many of the books in the Primeros Libros collection reflect this effort to bring together Spanish and Mesoamerican ways of knowing. The collection represents six indigenous languages as well as Spanish and Latin. Spanish missionaries translated religious texts and prayers into languages like Nahuatl, Zapotec, Mixtec, and Otomí. Through this work, they reduced indigenous speech to their own realm of visual images using alphabetic symbols and European writing systems. Mesoamerican indigenous languages thus became objects of knowledge at the hands of missionaries.

Rincón’s Arte mexicana is just one example of this kind of work. Rincón was among the first Jesuit priests in New Spain to be a native speaker of Nahuatl, and scholars consider him to have been the first grammarian of indigenous descent in the Spanish Americas. During the second half of the sixteenth century, he actively promoted Christian evangelization of Nahuas, taught the Nahuatl language to other priests, and wrote one of the earliest grammars of his native tongue.

During the 300 years of imperial Spain’s rule of Mexico, mendicant friars and grammarians wrote fifty-seven indigenous language grammars (artes) and dictionaries (vocabularios) to support the task of converting the native population to Christianity. While the bulk of colonial-period grammars and dictionaries dealt with Nahuatl, other Mesoamerican languages, such as Otomí, P’uréhpecha, Zapotec, Mixtec, and Maya, became objects of linguistic study using Western European frameworks (McDonough 2014, 46). In the sixteenth century, this included three grammars (by Andrés de Olmo, Alonso de Molina, and Rincón) dedicated to Nahuatl alone.

The challenge of the “Reading the First Books” project is to produce a tool that can faithfully transcribe books like these. Our goal is to improve the accessibility and discoverability of these often-overlooked texts. We want to create new opportunities for scholars to engage with these historical documents. At the same time, we have an opportunity to look critically at our own work. We ask: Is building a machine to transcribe colonial books itself a colonial act?

Transcribing the Primeros Libros

Automatic transcription tools work by analyzing the visual qualities of each character on the page, seeking to match each image to a statistical model of what the alphabet looks like. When the characters are hard to decipher, as is often the case in early-modern documents, the tools draw on context to improve their guess. Much the way we, when given the sequence “My name i_,” can fill in the missing letter “s,” the automatic transcription tool uses a statistical understanding of linguistic patterns to recognize difficult characters.

Early-modern books like Rincón’s Arte mexicana are particularly difficult to transcribe automatically. The problem lies in the “statistical understanding of linguistic patterns” and its limitations. When we started working with Ocular, the transcription tool for historical documents that we use for our research, we found that it expected all documents to conform to a single linguistic structure: English. Clearly, this wouldn’t work for the Mexican books. Worse, it felt like a return to the colonial era, when Spanish friars tried to force indigenous languages into the conventions of the dominant language. The only difference is that now English was dominant, instead of Spanish.

When we began the project that would become “Reading the First Books,” our first challenge was to try to work against these technological limitations. We were fortunate to be able to collaborate with computer scientists and linguists who helped us to modify Ocular so that it could work on multilingual texts, like the grammars and dictionaries in the Primeros Libros collection, as well as languages like Spanish, Latin, Nahuatl, and Zapotec. We also worked to improve Ocular’s ability to handle historical patterns in spelling, so that it better replicates the writing styles of the early colonial period. Ocular can also “modernize” transcriptions, which makes the text easier to search.

Still, there are four languages for which we were unable to build models because we couldn’t find enough sample texts on which to train our system. We hope in the future to collaborate with researchers who work in those languages so that we can further extend our project’s usefulness.

Our second challenge was to make Ocular easier to use for outside researchers, especially those working with larger collections of books. To accomplish this, we partnered with the Early Modern OCR Project (eMOP) at Texas A&M University. (OCR stands for optical character recognition.) Our plan was to incorporate Ocular into their preexisting interface, a website that allowed users to view a list of books, select the ones they wanted to transcribe, and run the transcription software with a simple click.

We encountered problems here, too. The original interface couldn’t display any accented characters, meaning that many of the book titles and authors’ names in our collection turned into gibberish. It also wasn’t flexible enough to handle many of the features that allowed our system to work on multiple languages or to handle historical spelling patterns. Fortunately, Texas A&M’s development team was excited about the possibilities of the project, and ended up fully redesigning their interface to improve a number of features, including those unique to our project.

As a result, we can now transcribe large collections of historical books, in multiple languages, from a web browser! We hope that this will end up being useful for other researchers working to transcribe digital collections. It will certainly be useful for us as the Primeros Libros collection continues to grow.

Digital Futures for Colonial Books

The “Reading the First Books” project was designed to be completed in August 2017. To celebrate the project’s conclusion, LLILAS Benson hosted a symposium in May 2017 that brought together researchers, developers, librarians, and students to present and discuss the project’s accomplishments, to think about the future of the digital materials it developed, and to imagine how digital scholarship will facilitate further engagement with colonial Latin American materials more broadly.

One goal of the symposium was to draw attention to the productive relationship between librarians and researchers, which is at the heart of “Reading the First Books.” Digital projects are often oriented around research questions: How can we teach machines to read historical texts? What can large corpora of colonial documents teach us about history and linguistics?

At the same time, digital projects depend on close collaborations with librarians and information professionals. Interface development, data management, metadata, and web display were all facets of “Reading the First Books” that depended on guidance from information professionals at the University of Texas Libraries and the Benson Latin American Collection.

Because “Reading the First Books” was born out of the ongoing collaboration between the Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies (LLILAS) and the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, building relationships among researchers and librarians has been a priority. To accomplish this goal, we modeled our project on the Latin American Digital Initiatives at LLILAS Benson.

The collaborative, multidisciplinary nature of “Reading the First Books” is reflected in the variety of forums where this research has been presented, which include the Modern Language Association, the Latin American Studies Association congress, and the Society of American Archivists. Speakers at the closing symposium included faculty members, librarians, and other individuals whose work bridges the gap between researchers and librarians. In addition to its contributions to technological development and historical research, we hope that “Reading the First Books” will serve as a model for library–faculty partnerships in the development of colonial digital scholarship.

Hannah Alpert-Abrams is a CLIR postdoctoral fellow in Data Curation and Latin American Studies at LLILAS Benson. She earned her PhD in comparative literature from The University of Texas at Austin in 2017, where she wrote her dissertation on the reproduction and circulation of documentary history from colonial Mexico. She managed the “Reading the First Books” project from August 2015 to August 2017.

Maria Victoria Fernandez is a graduate student at The University of Texas at Austin completing a dual master’s degree in Latin American Studies and Information Studies. For the past year she has worked as the Digital Scholarship Graduate Research Assistant on the “Reading the First Books” project.

References

Errington, Joseph. 2008. Linguistics in a Colonial World: A Study of Language, Meaning and Power. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

McDonough, Kelly. 2014. The Learned Ones: Nahua Intellectuals in Postconquest Mexico. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press.