BY BROOKE WOMACK and SUSANNA SHARPE

A librarian and two truckers are on a mission. They will travel for 27 hours, through four states, and at least one of them won’t get much sleep. Their journey involves high-security cargo, a climate-controlled 18-wheeler, and some rare documents from the 16th century. There will be truck stop food, photos with Snapchat filters to document the trip, and, by the end, an invitation to a wedding.

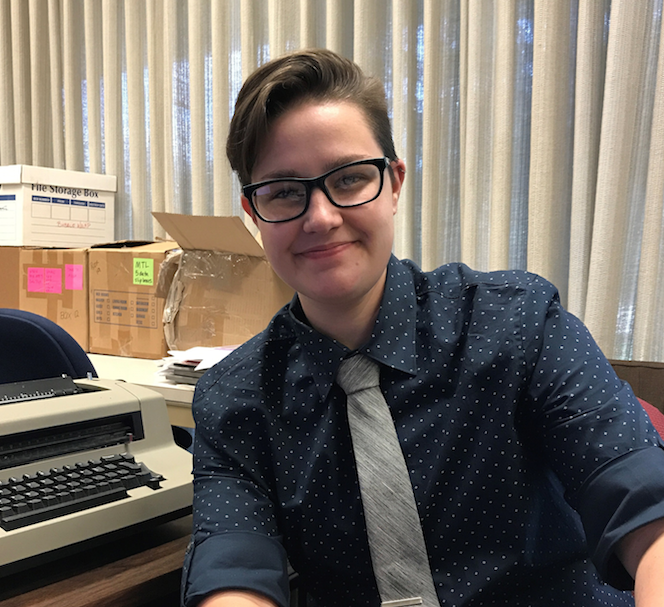

Last summer, librarian Brooke Womack was assigned the task of escorting some priceless cargo from the Benson Latin American Collection on a journey from Texas to California. The Huntington in Los Angeles had arranged to borrow four 16th-century documents from the Relaciones Geográficas collection held by the Benson for an exhibition titled Visual Voyages: Images of Latin American Nature from Columbus to Darwin. The show is part of the J. Paul Getty Museum’s Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative, a “far-reaching and ambitious exploration of Latin American and Latino art in dialogue with Los Angeles” that involves collaboration of art institutions across Southern California.

The Relaciones Geográficas, or RGs, are a collection of maps and written questionnaires that were commissioned by the Spanish Crown in 1577 in an attempt to document the population, demographics, languages, terrain, vegetation, and other details of the area known as New Spain. Many of the maps in the collection were created wholly or in part by indigenous artists. The two maps sent to California for display were Guaxtepec (Tepuztlan), Mexico, dated September 24, 1580 (a map of present-day Oaxtepec, Morelos), and Atitlán, Santiago, Guatemala, dated February 1585. The questionnaires are Relación de Metztitlan and Relación de Gueytlapa.

Womack’s journey to California as “guardian of the RGs” gives us a glimpse into how rare and priceless materials are handled in the world of library and museum lending. Womack explains that the process of safely packing and transporting the 16th-century documents was extensive and elaborate. “For the crating of the RGs, we used MasterPiece International, who built and packed the crate,” Womack said. “It took them about two weeks prepare the crate, and then they came to the Benson to pack and secure the RGs. We did all of this in the first floor rare stacks. It took roughly an hour to get the crate in, get it packed, and to secure the crate. Then the next week is when we loaded the crate into the truck.”

The trip would surely have been tedious and somewhat stressful, but Womack embraced the long hours on the road and the hourly checks on the precious cargo in its climate-controlled cabin with good cheer. Here are some excerpts from Womack’s notes on the journey, accompanied by photos that range from documentary to humorously doctored.

—Susanna Sharpe

June 28

After an hour-and-a-half of loading the crate, it was finally time to start the long journey to California.

Once the crate was loaded we secured it with a special lock. This lock not only secured the RGs better, but cutting said lock is a federal offense. Once that was secured, the back of the truck wouldn’t be opened again until we arrived at the Huntington Museum. Around 11 a.m. my truck drivers, Troy and Rhonda, and I headed south on I-35. Rhonda had the first driving shift so Troy could take a nap before driving through the night. Before we left Austin city limits, Rhonda spoke to my mom on the phone to quell her nerves about me traveling across country with two strangers. Our first stop was in Sonora, Texas. (When truckers are hauling a load, they have to go a minimum of 200 miles before they can stop for the first time.) In Sonora, we stopped at a little truck stop for supper. There was a Church’s Chicken that was out of chicken, so we went to the diner attached to the truck stop.

Our next stop wasn’t until the outskirts of El Paso, Texas. Troy and Rhonda switched at this point so that Rhonda could rest through the night. The sun was starting to set once we arrived in El Paso. Due to traffic and construction, it was close to 11 p.m. once we finally got into New Mexico. I think the longest part of the trip was just getting out of Texas.

June 29

After El Paso we headed into New Mexico. Nothing terribly exciting happened. It was pitch black outside, except when we rolled through towns, so I dozed on and off. I would wake up to check the temperature in the back of the truck (as I had to do once an hour) and make sure it was around 70 degrees for the RGs. Troy and I talked through most of the night.

We got into Arizona around 2 a.m. and I asked the truck drivers if we could make a quick pit stop. Around 3:30 a.m. Troy pulled over on the side of the road so I could take a photo next to the Benson, Arizona, city limit sign. We kept on trucking (pun intended) until right before sunrise and right before the California border so that Troy and Rhonda could make a shift change.

We got to California around 6 a.m. and the RGs and I watched the sunrise together. We only made one stop in Banning, CA. We didn’t stop again until we got to the Huntington Museum. At that point I’d been in the truck for 27 hours, slept for a total of maybe two hours during that time, been invited to Troy and Rhonda’s son’s wedding, and traveled over 1,300 miles with the RGs.

—Brooke Womack

Relaciones Geográficas: Sample Questions from the Spanish Crown

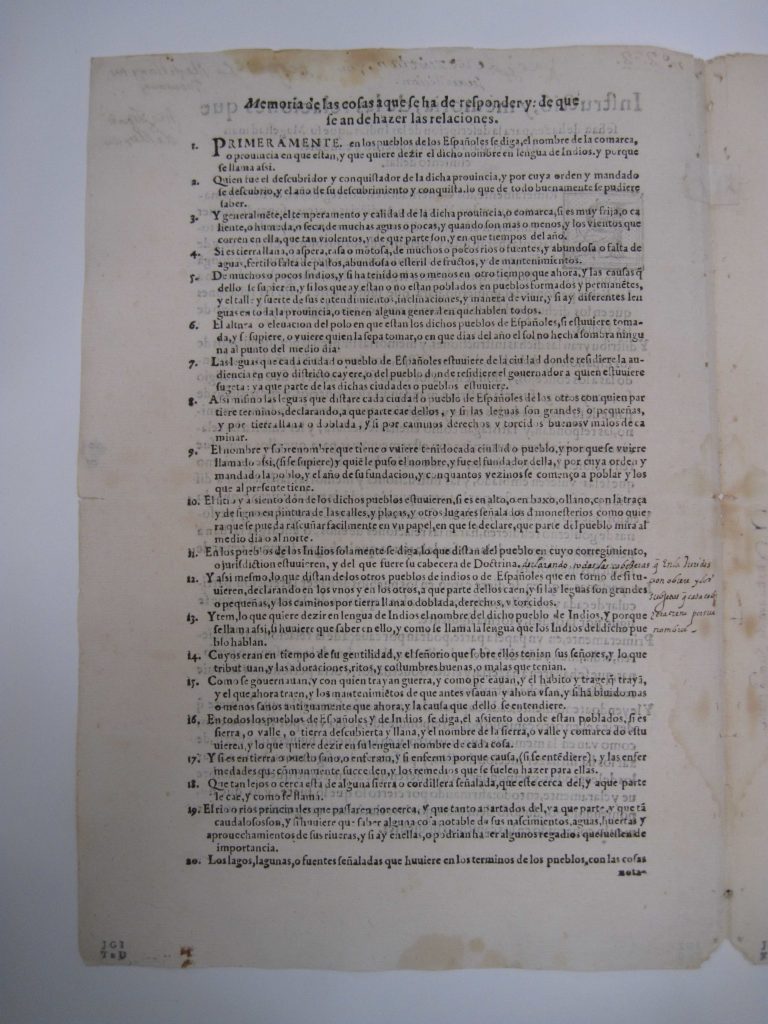

The encuestas distributed by the Spanish Crown consisted of 50 questions. Here is a sampling in Spanish, with translation. (Spellings reflect the original document.)

Memoria de las cosas que a se ha de responder y: de que se an de hazer las relaciones.

1. Primeramente, en los pueblos de los Españoles se diga, el nombre de la comarca, o prounicia en que estan, y quiere dezir el dicho nombre en lengua de Indios, y porque se llama assi.

Firstly, for towns of Spaniards, state the name of the district or province in which it lies. What does this name mean in the native language, and why is it so called?

2. Quien fue el descubridor y conquistador de la dicha prouincia, y por cuya orden y mandado se descubrio, y el ano de su descubrimiento y conquista. Lo que se todo buenamente se pudiere saber.

Who was the discoverer and conqueror of this province? By whose order was it discovered? In what year was it discovered and conquered, as far as is readily known?

3. Y generalmente, el temperamento y calidad de la dicha prouincia, o comarca, si es muy frija, o caliente, o humeda, o seca, de muchas aguas o pocas, y quando son mas o menos, y los vientos que corren en ella, que tan violentos, y de que parte son, y en que tiempos del año.

What is the general climate and character of the province or district? Is it very cold or hot, humid or dry? Does it have much or little rain, and when, approximately, does it fall? How violently and from where does the wind blow, and at what times of the year?

13. Y tem, lo que quiere dezir en lengua de Indios el nombre del dicho pueblo de Indios y porque sellama assi, si huviere que saber en ello, y como se llama la lengua que los Indios del dicho pueblo hablan.

What does the name of this [native] town mean in the indigenous language? Why is it called this, if known? What is the name of the language spoken by the natives of this town?

20. Los lagos, lagunas, o fuentes senaladas que huviere en los terminos de los pubelos, con las cosas notables que huviere en ellos.

What are the significant lakes, lagoons, or springs within the town boundaries? Note anything remarkable about them.

26. Las yeruas o platas aromaticas co que; se cura los Indios, y las virtudes medicinales, o venenosas de ellas.

What are the herbs or aromatic plants that the natives use for healing? What are their medicinal or poisonous properties?

33. Los tratos, y contrataciones, y grangerias de que biuen y se sustenta assi los Españoles como los Indios naturales, y de que cosas, y en que pagan sus tributos.

Through what dealings, trade, and profits do both Spaniards and Indians live and sustain themselves? What are the items involved and with what do they pay their tribute?