BY JOSÉ MONTELONGO

Deciding how to end a novel is the author’s privilege. To write novels for a living is a volatile career choice, at least when it comes to paying rent, but the destiny and shape of your characters is not volatile at all, it’s your prerogative—you are the one choosing when and how the narrative comes to a close.

A diary is narrative in nature, and yet the author does not control the ending. Sometimes the author doesn’t even know that the end is coming and is not within her power to add one more page, one more paragraph to the story. The life of the diarist is being written in the pages of the diary.

We know exactly how diaries end because the stuff they are made of—the raw material—always ends up in the same place. It ends down in the same place, approximately six feet under. The stuff a diary is made of is called life, which, despite its very predictable endings, happens to be a much more inventive author than, say, Balzac or Lope de Vega.

In fiction writing, the author chooses to accelerate or slow down the action. A flash-forward, for instance, provides a glimpse of how a certain character turns out, and it makes you wonder what happened in between. The diary is tied to a different time frame, one that might seem all too common, in which a year is a year and a day lasts all of 24 hours. Diaries follow the time of life and there is no literary trick that will allow your protagonist to live through many centuries or make time run in reverse so that your main character rushes back into the womb.

Through fidelity to diary-keeping and attention to subtle inner changes, the diarist weaves a unique cadence of storytelling. Its slow and granular qualities create an unfamiliar mode of narrative, which demands special interpretative strategies.

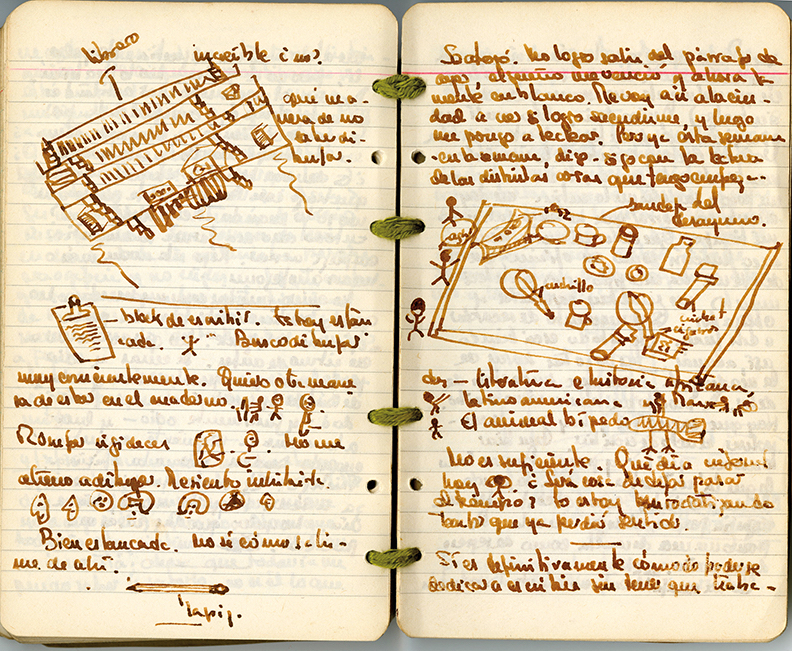

Some people keep diaries during moments of crisis or transformation—as instruments of self-discovery—hoping those pages can become an excursion toward the inside of the soul, a confrontation with the self. For other people a diary is not a temporary project of introspection but a daily and vital necessity. Such was the case of Mexican writer María Luisa Puga (1944–2004), whose diary, contained in 327 notebooks that span thirty-two years, was donated by the Puga family to the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection and is now open for research and consultation.

Fidelity to her diary was for María Luisa Puga tantamount to perseverance in her vocation as a writer. Map of her intellectual growth, witness to her readings, clean slate for drafting narrative projects, Puga’s diary was above all an existential log, as much corporeal as verbal. Fever and writing appear in the fourth entry of the first notebook: “I wish I could sculpt one word. I wish I could feel language very close to me. I wish I could breathe it. Yet at the same time I don’t care, I just don’t care. It must be the fever speaking, of course.” The fever broke and left her, the woman moved to different countries and back to Mexico, introspection became her tool of choice, and the notebooks grew into the laboratory not for her writing but for her being.

In a slim autobiographical volume published in 1990, De cuerpo entero, Puga recounts her formative years by describing the rooms where she lived in her childhood and youth, in Acapulco, Mazatlán, Mexico City, a handful of European cities, and Nairobi, Kenya. The diary, says Puga, was the portable version of Virginia Woolf’s room of one’s own.

My diary, the notebooks in which I have been writing since forever, in which I used to write little novels for my sister, used to come with me everywhere. Walking around in London, in coffee shops and parks, on the bus and the subway. When I got home I used to put it on the table, by the typewriter. The notebook is my tape recorder, my camera, my conscience, my writing gymnasium, the place for secret reactions, the place from which to judge the world. (p. 21)

In her early diaries, one can sense the temperature of the 1968 youth revolts, the wish to change life and transform society. “What if I changed entirely the direction of my life? If I truly started again from scratch? I’ve followed the same path since I was born. Maybe it’s impossible. My way of feeling friendship is one, but maybe there is a different way, the non-bourgeois way. Does that even mean anything? . . . Everything must change” (Notebook 4, Dec. 25, 1972). Packing your bags, jumping on the next train, moving abroad, breaking up with your partner, quitting your job, all those changes are symptoms of restlessness and dissatisfaction. The inner and the outer, everything must change.

Many notebooks contained a loose sheet with annotations written by Puga when she decided to read some of her own diaries twenty years later. She sees herself in a mirror that reflects an unquiet and plural image of her youth, and yet is able to recognize nuclei of meaning that started to coalesce back in the 1970s. “Here you can see the theme of romantic partnerships, the themes of writing, cities, and literature,” Puga writes on one of the loose sheets, dated 1992. Then she does some basic arithmetic: 1972 – 1944 = 28. “That is, I was 28 when I scribbled that notebook.” She looks back on her years in France, Greece, and Italy, when she read Musil, Dostoyevsky, Woolf, and when her to-read list included the following items: Frantz Fanon, urban architecture, essays on Latin America, women’s lib, and black power (Notebook 2, October 27, 1972.)

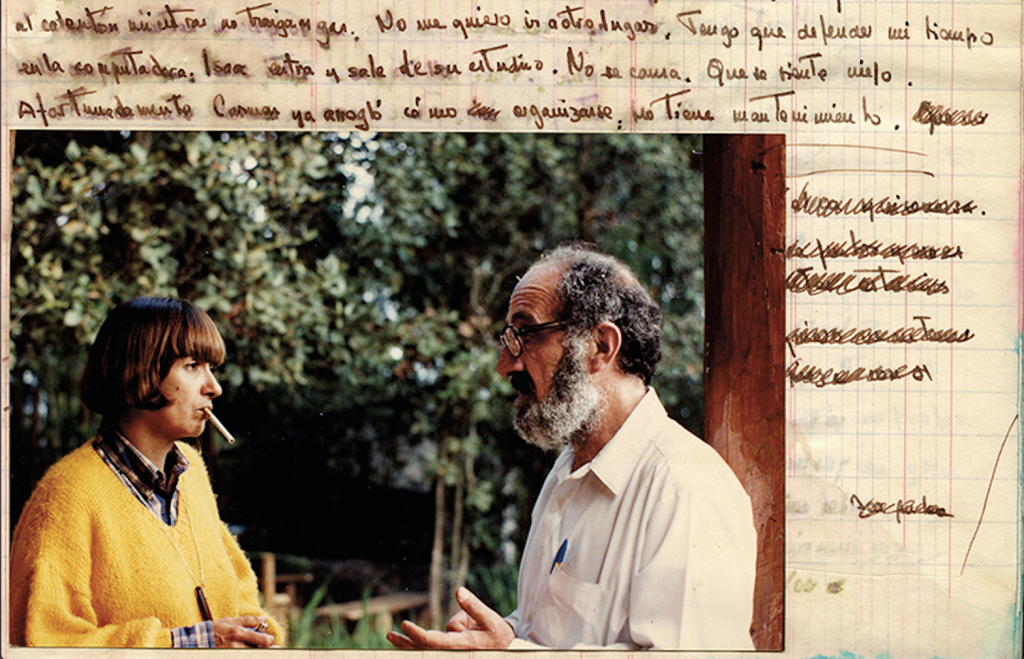

She had traveled to London in 1968 hoping to be back in Mexico within a year. It took her ten years to return, after a journey through several countries. When she finally did, she had finished her first novel, Las posibilidades del odio (1978), in which she decanted her observations of living in Kenya. Puga insisted that her experience of colonialism in Africa allowed her to see and understand her own country anew. Her second novel, Pánico o peligro, received the prestigious Xavier Villaurrutia Prize in 1983. Then she abandoned the literary scene of Mexico City and moved to a cabin by Lake Zirahuén, in the state of Michoacán. She led dozens of literary workshops for people of all ages, wrote novels, short stories, books for children, and a book about the ceramics of Hugo X. Velásquez. Her collection of book reviews (Lo que le pasa al lector, 1991) contains insights about her own narrative, flashes of Puga’s poetics as expressed in her vision of other writers’ technique.

Puga didn’t think that the students in her writing workshops were all supposed to become professional writers, but she knew how vital it was for them to master language. If we don’t, if we are unable to find the words to tell our own story, then language will master us. Prepackaged language, according to Puga, is a keen adversary of human experience. Political slogans take over our individual judgment; they do the thinking for us. Clichés disseminated through the media—cultural slogans—colonize our minds. Her goal in the workshops, and in her own literature, was to take back ownership of language. Puga’s diaries might be the part of her work in which this vital enterprise to appropriate language is most urgent and most evident. Those 327 notebooks—housed in the Special Collections Division of the Benson Collection—are waiting for their reader, their editor, and their interpreter.

José Montelongo is head of collection development at the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection at The University of Texas at Austin. He graduated from Washington University in St. Louis with a PhD in Latin American Literature.

Editor’s note: English translations of diary passages provided by the author. Leer un artículo sobre los diarios de Puga en español aquí.