BY SUSANNA SHARPE

WE DON’T OFTEN STOP TO THINK about why we speak the way we speak, or how some of our linguistic habits came to be. But this is one of the things linguists like Sandro Sessarego pay great attention to. Sessarego (pronounced seh-SAH-re-go), associate professor in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese, focuses on the habits of speech that set apart some Afrodescendant communities in the Spanish-speaking Americas.

Sessarego specializes in Afro-Hispanic varieties, the languages that developed in Latin America from the contact of African languages and Spanish in colonial times. A contact language results when the speakers of more than one language come together and develop ways of communicating with one another. There are different types of contact languages. For example, creole languages develop among speakers of mutually unintelligible languages. As such, they show “intense processes of contact-induced language restructuring,” says Sessarego. There are only two Spanish Creoles in Latin America: Papiamentu, spoken in the Dutch Caribbean islands of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao; and Palenquero, spoken in San Basilio de Palenque, Colombia, by descendants of a maroon community established by people who escaped slavery. These creoles diverge quite significantly from Spanish, so that neither of these languages is intelligible to a Spanish speaker.

Most Afro-Hispanic varieties, in contrast, are mutually intelligible with Spanish, yet they display a set of linguistic phenomena that make them highly interesting to scholars. Sessarego explains that these features are commonly seen in advanced second-language varieties of Spanish. For example, there is use of the pronoun where it would be dropped in most dialects of standard Spanish (Yo voy a la casa vs. Voy a la casa), and lack of gender and number agreement across the noun phrase (mucho persona simpático vs. muchas personas simpáticas). But the speakers of these Afro-Hispanic languages, who number in the thousands, are not second-language speakers. The languages they speak have been passed down for many generations.

In 2011, Sessarego published Introducción al idioma afroboliviano: Una conversación con el awicho Manuel Barra. This book takes a close look at Afro-Bolivian with a dual purpose: to provide a context of how Afro-Hispanic languages developed, and to describe the features of Afro-Bolivian in detail through various types of linguistic analysis (the book comes with a CD). Central to the book are transcribed interviews with awicho Manuel Barra, the eldest speaker of the language, who lives in the community of Tocaña, Nor Yungas, Departamento de la Paz, Bolivia. (Sessarego explains that awicho comes from the indigenous Aymara language, in which awicha means grandparent. Afro-Bolivians use awicho to refer to an elder man.)

Sessarego’s transcription of his conversations with Barra represents the first document published entirely in the Afro-Bolivian language. Beyond its linguistic value, Sessarego points to the document’s significance as “an authentic and important example of what was and is the life of the Afro-Bolivian people, an ethnic group that has been exploited and segregated for centuries simply because of their skin color.”

Sessarego emphasizes the importance of his study beyond the academic. For him, it was a way of “giving back to the community, spreading awareness, and taking stigma away” in a community where speakers of the language have been made to feel shame. The book’s publication led to visibility and legitimacy for Afro-Bolivian, including the launch of a radio show on Afro-Bolivian Spanish and language policy. “This and other publications have led many members of the local community to take a new look at their traditional language, previously regarded by some as a sort of embarrassing ‘broken Spanish,’” says Sessarego. “Luckily, the local attitudes toward this variety have greatly changed. Afro-Bolivians have recently created the Instituto de Lengua y Cultura Afroboliviano with the aim of promoting and revitalizing their language, which is now perceived as a symbol of cultural and ethnic pride.”

In studying Afro-Hispanic languages and their speakers, Sessarego also looks at the cultural and social history of Black enslaved people, and the plantation societies in which they lived. He obtained law degrees in Italy and Spain in order to explore more deeply the role of legal status in the development of these societies. The legacies of Roman law versus Spanish law affected populations in different ways. The sixth-century Corpus Juris Civilis, the main Roman legal text dealing with slaves, held that slaves had no legal personhood. Later, the Siete Partidas of King Alfonso X (El Sabio, r. 1252–1284) would depart from that, conferring personhood and many associated rights on slaves in thirteenth-century Spain. These included the right to accumulate property, to accuse someone in court, to (Christian) education, to marriage, and to keeping the children of a marriage.

The Spanish colonies applied the legal framework of the Siete Partidas to Black slaves in the Americas, in contrast to the Dutch, for example, who applied a legal system much closer to ancient Roman law to regulate slavery. Sessarego points out that in places where Spanish law applied, we see the development of Afro-Hispanic dialects, while in contrast, Papiamentu and Palenquero, the only two Latin American Spanish-based creoles, are spoken in places where Spanish law never applied. For slaves in Spanish territories, the ability to buy freedom led to Black people’s integration into the larger society, including learning Spanish. In combatting the sin of fornication, Catholicism also played a role in keeping Black enslaved families together, helping solidify Afro-Hispanic languages.

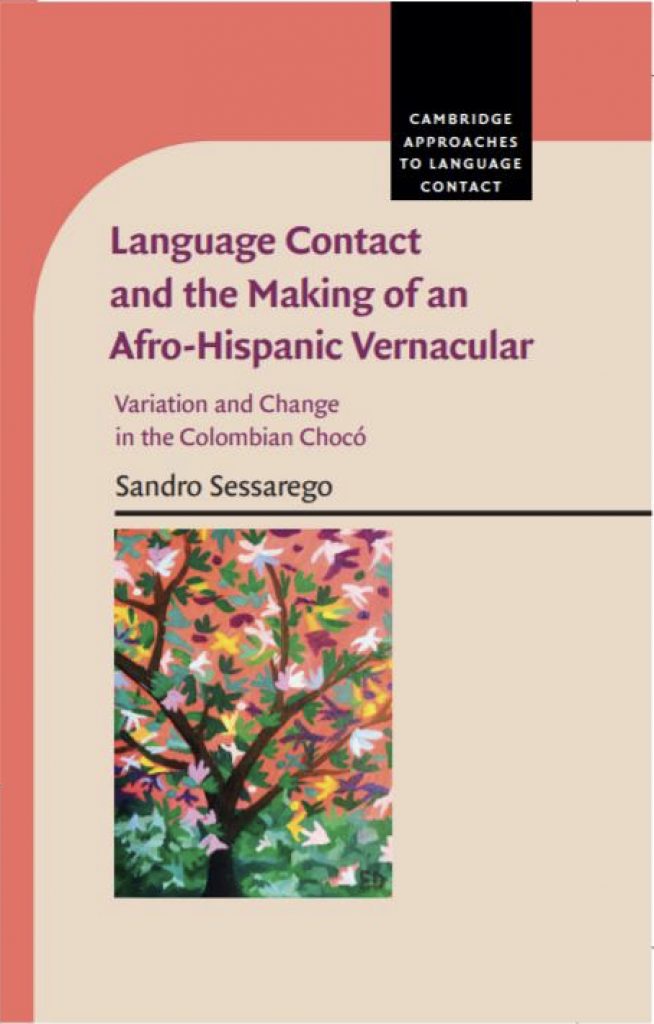

Sessarego writes and publishes on Afro-Hispanic languages and slavery in the Americas. In his latest book, Language Contact and the Making of an Afro-Hispanic Vernacular: Variation and Change in the Colombian Chocó (2019), he explores how different legal systems helped shape the relations between blacks and whites in the Americas, and the Afro-European contact language varieties that developed out of such scenarios.

Susanna Sharpe is communications coordinator at LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections, and editor of Portal magazine.