BY ALICIA GASPAR DE ALBA

BACK IN 1986, when Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz first started speaking to me in my dreams, I would be talking to her on the phone—that old rotary black phone my grandparents used to have—but I could see her clearly, wearing her black and white Hieronymite habit and my black wingtips. I had the same dream enough times to know that my subconscious was trying to tell me something. Was Sor Juana walking in my shoes, or was I supposed to in-habit her life? That we were on the phone clearly meant she was trying to communicate with me. With a master of arts degree in English–Creative Writing, I had my heart set on becoming a novelist, and had been intrigued by Sor Juana since I was a child, listening in rapt wonder to my uncles and cousins reciting her famous poem about “stubborn men who accuse women for no reason.”

Maybe the dream was telling me that I had to write a novel on Sor Juana, that I had to filter her story as a seventeenth-century Mexican nun/poet/scholar (symbolized by her habit) through my vision as a late-twentieth-century Chicana lesbian writer (symbolized by my wingtips).

At the time, I was living in exile from academia. I had started my PhD in American Studies at the University of Iowa in fall 1985, but after two semesters, I was disenchanted, not with Iowa City but with the field itself, and with the whiteness of the program, its jargon stultifying and meaningless to the activist work I saw myself doing in the academy. I moved back to El Paso to regroup, but soon discovered I had to leave home for good if I ever expected to live my own examined and independent life. Boston was my next place of residence, which I figured could be a great place to live the writer’s life. Instead of wasting time trying to understand theory and methodology, the right side of my brain rationalized, it made sense for me to move to the East Coast, where I would be closer to the publishing industry, and perhaps even get an editorial job at a New York press.

The closest I came to working in the publishing industry was my job as a transcriber of books for the blind at the National Braille Press in Boston. Learning Braille as a sighted person was fun for the first three months, but the full-time job ended up being even more numbing to my writing career than academic jargon. After downgrading to a part-time schedule, I bought a used IBM Selectric typewriter, and committed to a writing life. Every day I would come home bleary-eyed after my short shift reading reliefs of Braille dots on a white page, put on some Mercedes Sosa or Silvio Rodríguez music, light a stick of Nag Champa incense, and sit at my makeshift desk with a stack of colored scratch paper to give myself over to writing the Great Chicana Novel on Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.1

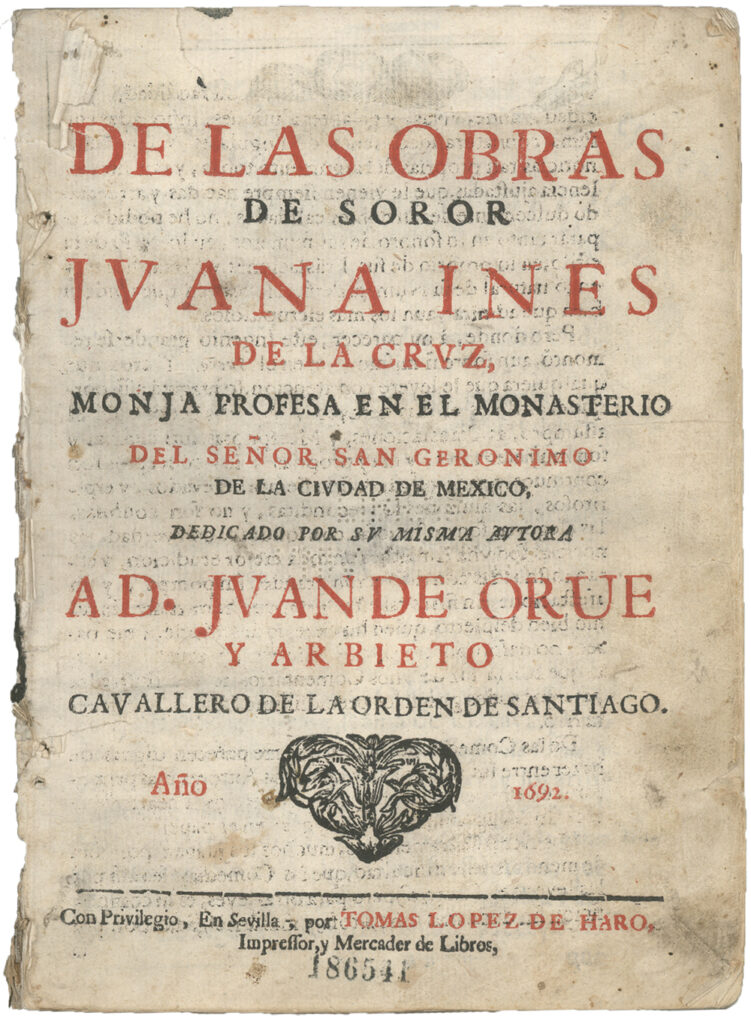

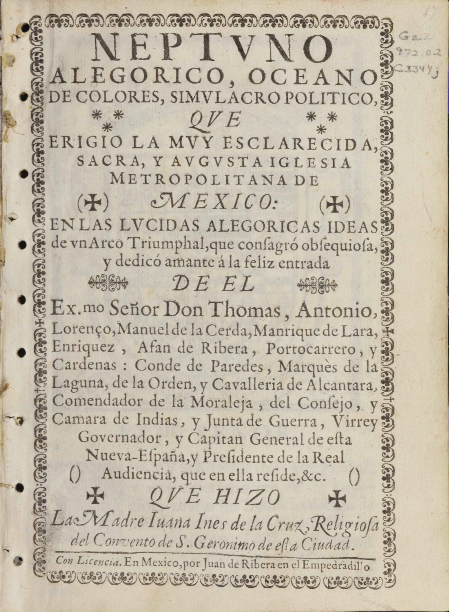

At the time I didn’t know very much about Sor Juana. Having grown up on the El Paso side of the border and attended English-only Catholic schools, I had not been introduced to this most famous woman in my Mexican heritage, beyond listening to my relatives recite her “hombres necios” verses.2 All I really knew about Sor Juana was that she was a great poet, an early feminist, an advocate for a woman’s right to an education, and that her image graced the old 1000-peso Mexican note. Obviously, before I could write about her, I had to read Sor Juana’s own work (preferably in her own baroque Spanish) and research her life and times in seventeenth-century New Spain. Indeed, I had to learn everything I could about life in a colonial convent, about Sor Juana’s relationships with her family, the other nuns, the priests who supported and attacked her, and most especially, her intimate friendships with other women, not to mention all the other minutiae that constitutes a historical novel.

Those were the days of no Internet, no Google, no Wikipedia, no YouTube, no open-access research materializing on the screen with the click of a button. In fact, there were no screens, no computers, no passwords, and research meant slogging through drawers of Dewey decimal reference cards to find the titles I was looking for, walking the stacks to locate the needed books, and perusing the shelves for any useful surprises. It was a surprise, in fact, that I found any sources relating to my research at the Boston Public Library, but my tenacity yielded some useful preliminary results, such as a copy of Francisco de la Maza’s Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Ante la historia, volume I of Alfonso Méndez Plancarte’s edited series Sor Juana’s Obras Completas, and Octavio Paz’s Sor Juana, o, Las trampas de la fe, all in Spanish, and in English, Irving Leonard’s Baroque Times in Old Mexico and Gerard Flynn’s Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. I also found a number of articles that I was able to locate via interlibrary loan.

By pure serendipity, I was invited to read my poetry at a Latino literature conference in San Antonio, Texas, where I met Margaret Sayers Peden, translator par excellence of the most iconic Latin American literature, including Sor Juana’s poetry and Octavio Paz’s Traps of Faith. The conference was connected to the International Hemispheric Book Fair, where at the booth of a random bookseller, I found three of the four-volume set of Sor Juana’s Complete Works (which I purchased for an unbelievable price of $60 for all three). It would take me a few years to locate the fourth volume on a dusty bottom shelf of a bookstore in downtown Mexico City. And then my mother gifted me with my own copy of Octavio Paz’s magnum opus.

My research bed was made, and now I just had to sleep in it for ten years before I was able to assemble all the pieces of my/Sor Juana’s story.

Octavio Paz, The Seminal Sorjuanista

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, o, Las trampas de la fe, then—and still—considered the ultimate resource on the seventeenth-century Mexican nun/scholar/poet, was particularly illuminating, and it was in Paz’s prologue that I first encountered a reference to one Dorothy Schons. In a very brief genealogy of twentieth-century scholars who have studied Sor Juana, apart from himself, Paz writes that “[l]as últimas en llegar fueron las mujeres,” implying that women scholars and writers came late to the study of Sor Juana. First among them, he lists Dorothy Schons. He quotes Schons extensively throughout Trampas de la fe, and the footnotes at the bottom of the page reference Schons articles published in 1926, 1929, and 1934. Keep in mind that Octavio Paz’s seminal essay on Sor Juana, “Homenaje a Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz en su tercer centenario (1651–1695)”3 was not published until 1951, so I’m perplexed about why he would say that the last to arrive at the study of Sor Juana were the women scholars and writers, when his own first text came 25 years after Dorothy Schons’s first publication!

To be fair, Paz credits Schons with writing the first tentativa, or attempt, at a feminist interpretation of Sor Juana by inserting Sor Juana’s life and work into the misogynistic history of seventeenth-century New Spain. “La erudita norteamericana trató de comprender el feminismo de la poetisa como una reacción frente a la sociedad hispánica, su acentuada misoginia y su cerrado universo masculino.”4 And yet, in a manifestation of his own accentuated masculine ego, he discredits her authority by saying that unfortunately Schons never published more than two or three articles on Sor Juana, and not having published a book, all she left were a few “atisbos aislados,” or isolated inklings of an interpretation.

Book or not, he certainly availed himself generously of her research and her insights. I wonder why Paz chose not to cite Dorothy Schons’s 1925 essay, “Sor Juana: The First Feminist in the New World,”5 where she makes her argument for Sor Juana’s proto-feminist standpoint quite clear and persuasive. There were reasons she never published a book on Sor Juana, which I will discuss later. Let me just reiterate here, that it was not Octavio Paz who baptized Sor Juana “the first feminist in the New World,” but Miss Dorothy Schons, while still a PhD student, a full 25 years before Octavio Paz published his first essay6 on Sor Juana that ended up being the generative piece for Trampas de la fe—now considered the Sor Juana Bible.

Dorothy Schons, The Original Sorjuanista

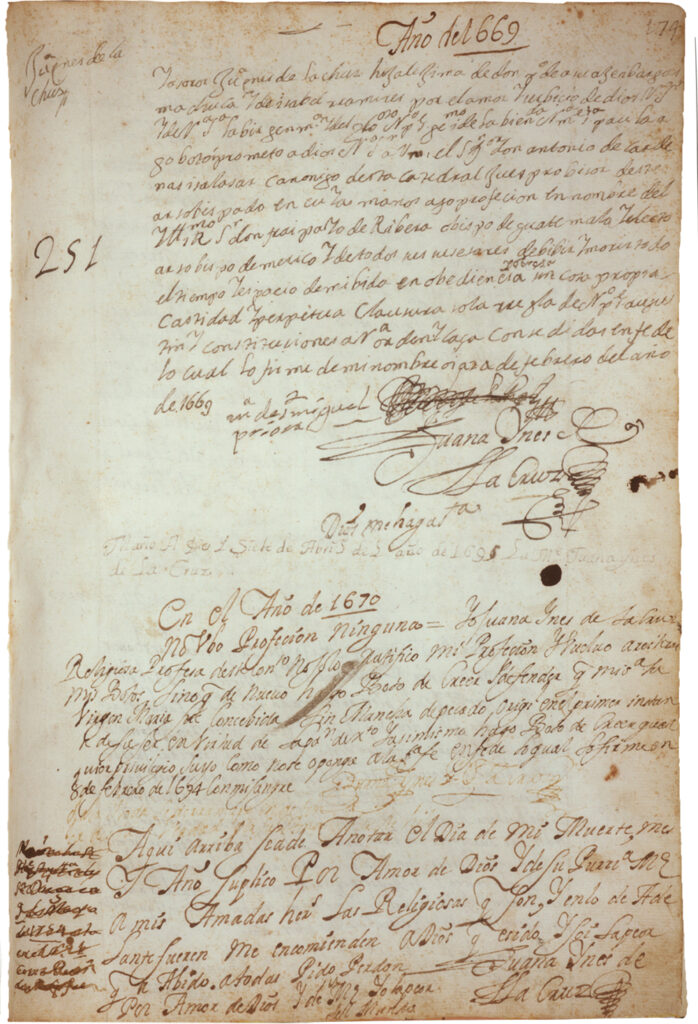

Unless you have gone to the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection at The University of Texas at Austin, and requested the Dorothy Schons Papers, you will have missed two of the most important documents of Sor Juana lore ever collected. The first is the more than 300-year-old Libro de Profesiones, or Book of Professions, of the Convent of Santa Paula in Mexico City, in which 350 novices over a period of more than a century inscribed their Testaments of Faith to enter life in religion as Hieronymite nuns. Thirty years ago, when I first set foot in the Benson, it was possible to take the ancient book out of its archival box with your own gloved hands and study the original page on which Sor Juana first signed her vows to the convent in 1669, which she renewed 25 years later in her own blood. It was hard to see the “la peor que ha habido . . . peor del mundo”7 designation she gave herself at her vow-renewal, but if I squinted hard enough, I could make it out, her signature in that brown ink stain of dried blood in which she mortgaged her life and soul to the convent for the second time. I cannot say how long I stared at that page, but my hand was trembling as my palm hovered over the writing. I so much wanted to touch her dried blood with my own flesh. Catholic upbringing, you know.

y vicarias del Convento de San Gerónimo,” 1586–1713, which Sor Juana

signed in ink and her own blood. Dorothy Schons Papers. Benson Latin American Collection.

The second fascinating discovery in the Schons archive is an incomplete original manuscript, most of the pages typewritten, a few in carbon copy, of the first English-language novel on Sor Juana, written by Dorothy Schons circa 1930 and titled, “Sor Juana: A Chronicle of Old Mexico.” In the preface, Schons unequivocally situates Sor Juana’s life within feminist history by likening the nun’s struggle to the suffragist cause: “Two hundred years before Susan B. Anthony initiated the feminist movement in this country, there appeared in the New World a woman who was undoubtedly one of the earliest American Feminists. Strange as it may seem, this woman was a Mexican nun” (quoted in Sabat-Rivers, 939).

A few lines later, Schons segues from feminism to decolonial feminism: “What [Sor Juana’s] environment did to her, [is what] Mexico’s past has done to the Mexican people. . . . Mexico’s plea for social justice arises out of social inequalities inherited from colonial times.”8 Schons’s novelized interpretation of Sor Juana’s life intended to show that patriarchy had conquered Sor Juana as surely as the Spanish conquistadores colonized Mexico—leaving both collapsing under the social injustices wrought by the greed and cruelty of hombres necios.

With such a visionary interpretation, why is it that the contributions of Dorothy Schons to the sorjuanista canon are in fact not considered canonical works except by those critics in the fields of Golden Age Literature and Latin American Studies with more feminist inclinations?9 Because she was writing in the 1930s? Because she was a woman in academia at a time when there were few pedigreed female professors? Because the patriarchal academy did not expect female professors to be “scholars” or visionaries, but to provide essential services to their departments and universities such as grading papers, teaching languages, and assisting their male colleagues with manuscript editing? Or was there something more sinister going on, something that led to Professor Schons’s suicide in 1961? What follows is a summary of “some obscure points”10 on the life of Dorothy Schons that might shed some light on why this pioneering Sor Juana scholar all but disappeared under the huge shadow of Octavio Paz and the Golden Age sorjuanistas.

Surrender, Dorothy

Originally from Saint Paul, Minnesota, Dorothy Schons (1890–1961) taught in the Department of Romance Languages (now Spanish and Portuguese) at the University of Texas at Austin from 1919 to 1960. She earned her bachelor of arts degree at the University of Minnesota in 1912 (at age 21), started her master’s degree at the University of Chicago, and then was hired as a Romance languages instructor at UT Austin. She completed her master’s in 1922 (at 31) and stayed on at UT Austin as a PhD student and an instructor in the department. In 1927 (at 36), she ascended to the rank of assistant professor, and five years later, completed the requirements for her PhD (now, she’s 41). It wasn’t until 1943 (at 52 years of age) that she was promoted to associate professor. By the time she died (by suicide, according to her death certificate), 18 years later, she was still not tenured nor did she ever reach the rank of full professor.11

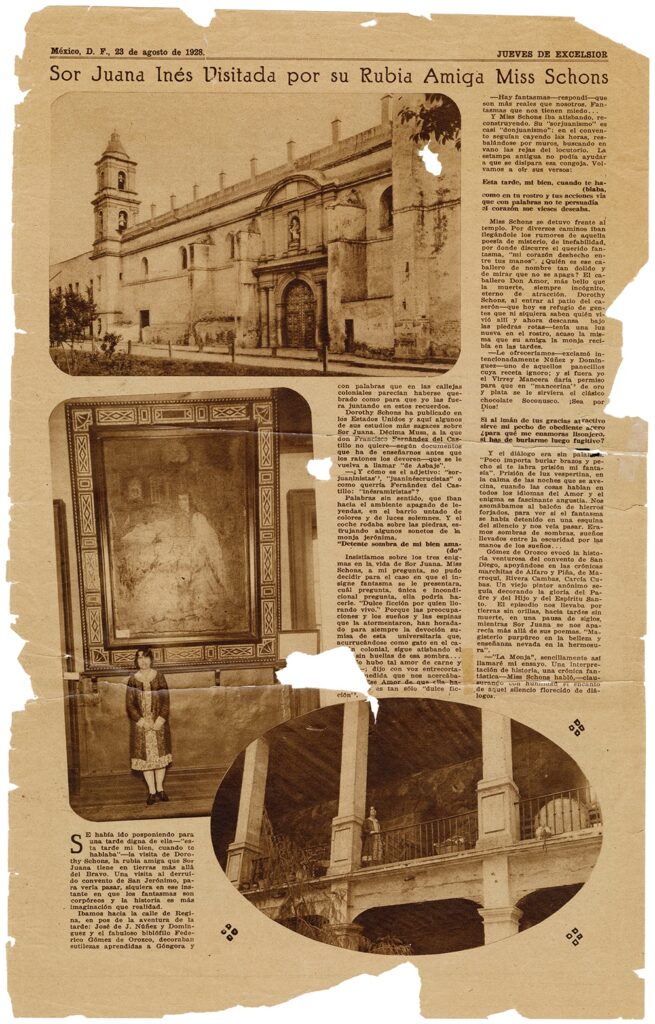

Mexico, D.F., August 23, 1928. Dorothy Schons Papers. Benson Latin American Collection.

After 41 years of labor and service to the University of Texas, after teaching thousands of students (including Georgina Sabat-Rivers, one of the most respected sorjuanistas in the field of Spanish letters), publishing six books and 50 articles on Hispanic literature, religious drama, and the nuns of New Spain, and winning important academic accolades in Mexico and Spain, how is it fathomable that Dr. Schons did not get tenure? In Dorothy Schons: La primera sorjuanista, Guillermo Schmidhumer de la Mora observes that, given her expertise and decades of research on Sor Juana, it seems odd that the topic of her dissertation was a male critic of Mexican comedy; he makes an informed guess that “perhaps her professors frowned on the practice of a woman researching another woman during a time in which Sor Juana’s fame as a literary and human figure had not yet become consolidated.”12 Indeed, after the death of this controversial figure, her name receded into the Mexican annals for 300 years and did not resurface until the early twentieth century, thanks to Dorothy Schons. Did her male colleagues at the University of Texas not know Sor Juana? Did they devalue Schons’s research on that Mexican nun due to some departmental bylaw or policy that dictated female professors could not research or publish on female writers? Did the “hombres necios” of the Romance languages department vote against her getting tenure, despite the many years of service Schons had given to that department, and despite the published evidence of her knowledge and accomplishments that would have merited her promotion?

Although Dorothy Schons was the first woman in Texas to earn a PhD, and the first female doctor of Romance languages in the United States, the institutional bias against women studying other women got her fired from her job. Her academic appointment was terminated in 1960 for failure to achieve tenure. Is it any surprise that, alone and grieving for her dead sister, unknown and unappreciated as a scholar, and unfairly dismissed from the career to which she had dedicated four decades of her life, she killed herself with a .32-caliber pistol on May 1, 1961, at the age of 70?13

Or did she?

In a five-act play, La secreta amistad de Juana y Dorotea, Schmidhuber de la Mora imagines what might have led to Schons’s tragic and violent end. By juxtaposing Dorothy’s and Juana’s encounters with their respective hombres necios, Schmidhuber de la Mora presents a plausible scenario of the excesses of patriarchal bias against women scholars, which did not end in Sor Juana’s century.

In Dorothy Schons: La primera sorjuanista, the critical biography he wrote in tandem with the play, Schmidhuber de la Mora is certain that Dorothy Schons conceived of Sor Juana’s life as intractably linked—“entrañablemente eslabonada” (73)—to her own personal biography. In writing about Sor Juana, particularly in the more subjective (and subjunctive) voice of her unpublished novel, Schons was writing about her own life-and-death struggles within the patriarchal academy that exploited her labor, appropriated her knowledge, and dismissed her as a woman.

In her comparison of the respective Sor Juana studies authored by Octavio Paz and Dorothy Schons, Georgina Sabat-Rivers asserts that not only did Schons in the 1930s have the capacity to see in Sor Juana what critics at the end of the twentieth century seem to be barely “discovering” about her, but also that Schons’s “express intention was to center her interpretation on the personality of the woman Sor Juana had been, and to explain her reactions within this context. . . . As a woman, Schons could not admit that Sor Juana [at the end of her life] felt terrified and submitted to her fears, as Paz suggests, because that would have given the feminine sex a fundamental weakness that was unacceptable.”14 Having been trained by Schons, Sabat-Rivers was no doubt speaking from an empirical perspective that her former professor not only saw herself in Sor Juana, but also contextualized Sor Juana’s life and work within the feminist struggle against the patriarchal oppression of women.

Decolonizing the Other

Schons’s story of Sor Juana’s resistance to her oppressive “environment,” and her use of Sor Juana’s story as a palimpsest of how a great indigenous civilization was conquered by the Spanish colonizers who wrought social injustices (not to mention biological warfare through disease and murder) on the native peoples that populated the “New World” shows an early awareness of a gendered and racialized consciousness decades before such a consciousness came into its own. Today we call this consciousness decolonial feminism, a feminist praxis that, as Chicana historian Emma Pérez writes, “decolonizes otherness”15 by using the Other (Sor Juana) as the speaking subject rather than seeing her as the object who must be “spoken about [and] spoken for . . . who cannot know what is good for [her], who cannot know how to authorize [her] own narrative.”16

To decolonize Sor Juana’s “otherness,” we must first locate the speaking subject’s different and often contradictory sites of identity, the intersectionality of gender and race, ethnicity and language, sexuality and social location, that constitutes the speaking subject’s voice and story. Rather than trying to discern in Sor Juana’s most famous verses those literary elements that evoke or derive from some canonical male writer, those “Gongoresque” or “Calderonian” influences that some sorjuanistas are so fascinated by in her work, why not simply attribute the genius of those lines to Sor Juana? Because that would make her the speaking subject, and that would grant her agency, and that would mean she, as a woman, was bestowing upon herself the authority to write, read, and publish whatever she wanted, and that as a nun, she was breaking her vows of silence, humility, enclosure, and poverty. Sor Juana’s celebrity during her lifetime was outside the norm, and therefore Other; but insomuch as her illuminated mind was constructed as a manifestation of her “masculinity,” then she could be admired, envied, recognized on the one hand, and punished, censured, and silenced, on the other.

Ample evidence exists that both Sor Juana and Dorothy Schons were “other” in their respective worlds, women with brilliant minds and a talent for research and writing who saw too clearly the oppression of their sex by “hombres necios” who resented their intelligence, their influence, and their accomplishments, and went out of their way to orchestrate the conditions that eventuated in their demise. We decolonize them by listening to their stories, by scrutinizing the sexual politics, the power dynamics, the struggles, the victories, and the defeats each had to contend with in her day and locating them within the sisterhood of revolutionary women.

In the apologia to her novel, Dorothy Schons explains that she wrote a fictive treatment of the life of this most illustrious Mexican nun because there was little scholarship available on a figure who had seemingly passed into critical oblivion 300 years after the apex of her fame and glory. Nor did she find any secondary sources that would substantiate her standpoint epistemology of Sor Juana as the first feminist of the Americas. The personal details and ruminations of “A Chronicle of Old Mexico,” then, can only come from two places: Sor Juana herself, and Schons’s “decolonial imaginary.” By extrapolating the personal details Sor Juana left us in her own poetry and epistolary work, by paralleling Sor Juana’s struggle against the Church patriarchs of the seventeenth century with her own stubborn positionality as an anomalous Golden Age scholar whom her male colleagues were trying desperately to discredit, Schons’s novel portrayed the feminist woman behind this enlightened mind.

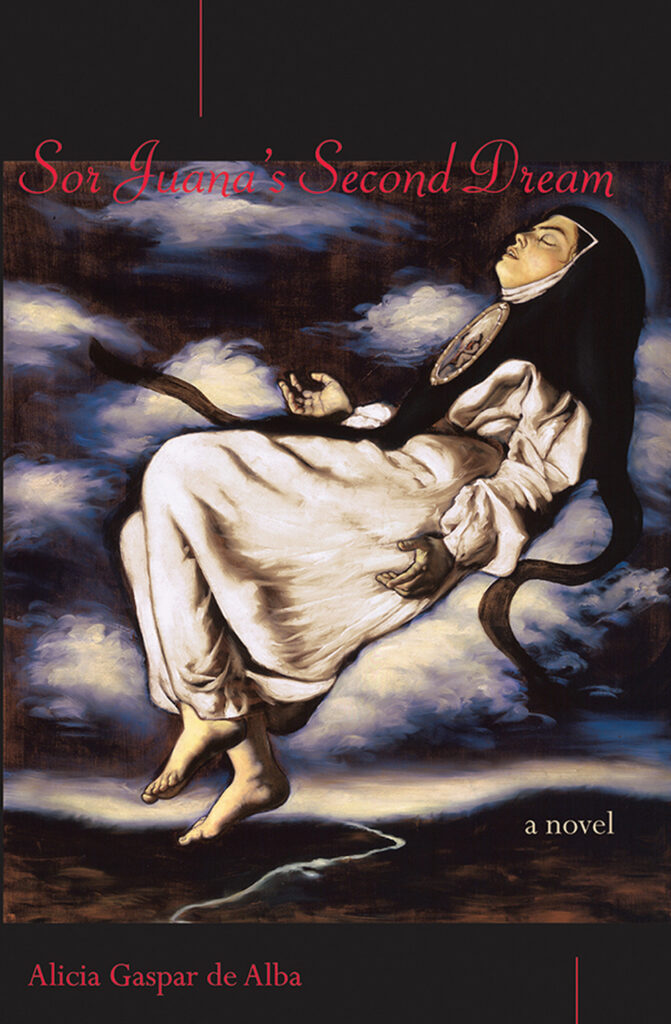

Francisco Benítez, Sor Juana, 1999, oil on canvas. Courtesy University of New Mexico Press.

In a similar way, I constructed my unapologetic, lesbian interpretation of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. By focusing on Sor Juana’s own words and primary sources (walking in her shoes), by listening to the silences that she purposefully inserted into her texts (in-habiting her life), by filtering her irreducibly closeted story through the intersectional parameters of my own Chicana lesbian writer/academic/poet’s subjectivity, my novel and my critical essays on Sor Juana exercise a decolonial feminist revision of Sor Juana’s story. As I wrote elsewhere, “This rewriting of [Sor Juana’s] colonial narrative from a Chicana lesbian female symbolic is how I track Sor Juana’s agency across the colonial landscape of both New Spain and the Sorjuanista imaginary.”17

If there is such a thing as poetic justice in academia, the fact that my archives are also in the Benson Collection at UT Austin, along with those of contemporary feminist thinkers, poets, and scholars Gloria Anzaldúa, Norma Cantú, Carmen Tafolla, and others, might provide some solace to the solitary soul of Dorothy Schons. Perhaps Dorothy’s spirit will tiptoe into the Alicia Gaspar de Alba Papers, find those eight boxes of first drafts and turn those archived pages with her ghostly fingers, reading with abandon those graphic scenes of Sor Juana’s auto-erotic moments and her lovemaking with la Condesa that I had to leave on the cutting-room floor when revising the manuscript for publication. Perhaps these sexual and quixotic scenes will shed a different light on the tortured and penitent Sor Juana she penned in “A Chronicle of Old Mexico,” and help her revendicate Sor Juana as a predecessor of Susan B. Anthony.

I called my novel Sor Juana’s Second Dream because, in opposition to her own First Dream, in which the Queen of Night (the Moon) loses her daily battle with the Light of Male Reason (the Sun), I wanted to imagine what her life might have been like had she actually done more than dream about giving free rein to her dark desires for another woman. My story thus extrapolates non-conventional poetic clues from Sor Juana’s primary texts—such as the poem in which she eats the secret note sent to her by “the palace,” i.e., la Condesa—that reveal to those of us who can “hear [her] with [our] eyes”18 what kind of Sister she really was, a sister who loved and was loved by another woman, her mind and her flesh.

What if, I mused, the outcome of her First Dream had been different, if passion rather than reason had won the battle between the Sun and the Moon? What would our lives be like today if Sor Juana’s conocimiento (and the accumulated knowledge of all the women mystics, scholars, philosophers, and poets who preceded and followed her) had inspired, rather than threatened, the enlightened minds of her/their/our generation?

Perhaps this is the Third Dream.

Alicia Gaspar de Alba is a writer/scholar/activist who uses prose, poetry, and theory for social change. She is the author of fiction and nonfiction works, including the award-winning Sor Juana’s Second Dream (1999) and Desert Blood: The Juarez Murders (2005). Gaspar de Alba is professor of Chicana/o Studies, English, and Gender Studies at UCLA. aliciagaspardealba.net

Notes

1. See Alicia Gaspar de Alba, Sor Juana’s Second Dream: A Novel (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1999). First edition. The novel was awarded the 2000 Latino Literary Hall of Fame Award for Best Historical Novel.

2. From her “Philosophical Satire,” Sor Juana’s most famous redondilla, often cited simply as her “Hombres necios” poem (Foolish Men, or Stubborn Men), written by Sor Juana circa the late 1670s–early 1680s. For the full text of the poem in more contemporary translation, see Alan Trueblood, A Sor Juana Anthology (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988), 111–113.

3. Octavio Paz, “Homenaje a Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz en su tercer centenario (1651–1695),” Sur, No. 206 (December 1951): 29–40. Downloaded from The Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Project at Dartmouth College on June 1, 2020.

4. Octavio Paz, Sor Juana, o, Las trampas de la fe (Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1987), 96. Translation: “The erudite North American woman tried to understand the feminism of the poet [Sor Juana] as a reaction to Hispanic society’s accentuated misogyny and closed masculine universe.” This is a reference to the unpublished novel of Schons, which Paz clearly read, but fails to cite in his book.

5. Dorothy Schons, “The First Feminist in the New World,” Equal Rights, official organ of the National Woman’s Party, 12, 38 (Oct. 31, 1925): 302. See also Georgina Sabat-Rivers, “Biofgrafías: Sor Juana vista por Dorothy Schons y Octavio Paz,” Revista Iberoamericana 51, nos. 131–132 (July–December 1985): 927–937.

6. Indeed, there were other publications about Sor Juana that followed Schons and preceded Paz by scholars from both sides of the border as well as from Spain, including one published in 1933, by a Mexican male scholar, Carlos E. Castañeda, who also called Sor Juana the “first feminist of America.” Nonetheless, it is Nobel laureate Octavio Paz who is credited as the ultimate authority on Sor Juana, and not a midwestern woman who called herself Sor Juana’s “rubia amiga,” or blonde friend, and who made the study of Sor Juana her life’s work. And there are other, mostly male, scholars who are credited with expertise about Sor Juana, among them her biographers Diego Calleja, Fernando de la Maza, Hermilo Abreu Gómez and Alfonso Mendez Placarte, the Mexican writer Amado Nervo, and the poets Gabriela Mistral and Rosario Castellanos. U.S.-based Latin Americanists and sorjuanistas like Emilie Bergmann, Amanda Powell, Stephanie Merrim, and Nina Scott are some of today’s English-language feminist interpreters of our Tenth Muse/Décima Musa. Nowadays, plenty of popular sources abound as well. YouTube alone is filled with short and long videos on Sor Juana’s life from all over the world, created by a range of Sor Juana aficionados—students, scholars, filmmakers, writers, musicians, and meme-makers.

7. This self-designation has been translated as “I, the worst of all,” and is used as the title for María Luisa Bemberg’s 1990 film on Sor Juana. A more literal translation would be “the worst [woman] there has ever been, the worst in the world.”

8. Dorothy Schons, “Sor Juana: A Chronicle of Old Mexico,” n.p. Dorothy Schons Papers, 1586–1955, Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, The University of Texas at Austin.

9. The Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Project, a website, or “comprehensive Sor Juana online bibliography,” sponsored by the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at Dartmouth College, does not include Dorothy Schons in its Bibliography of Contemporary Sor Juana scholars (nor yours truly, by the way), but it does list two books and 24 articles of Georgina Sabat de Rivers (aka Sabat-Rivers), who is called “[t]he leading Sor Juana scholar in the United States. She has dedicated her intellectual life to the study of Sor Juana’s life and works. She presented her dissertation, ‘El Primero sueño de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: tradiciones literarias y originalidad’ at Johns Hopkins University in 1969.” Not coincidentally, Sabat-Rivers was a student of Dorothy Schons at the University of Texas. The page was last updated on February 22, 2004. Accessed on May 29, 2020.

10. I’m alluding here to Dorothy Schons, “Some Obscure Points on the Life of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz,” Modern Philology 24, 2 (November 1926). Reprinted in Feminist Perspectives on Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, ed. Stephanie Merrim (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1991), 38–60.

11. See Guillermo Schmidhuber de la Mora, Dorothy Schons: La primera sorjuanista, con la colaboración de Olga Martha Peña Doria (Buenos Aires, Argentina: Editorial Dunken, 2012), 9–13. Author’s translation and summary.

12. Ibid., 12. Author’s translation. Original: “acaso porque sus profesores infravaloraban que una mujer investigara a otra mujer en un tiempo en que la figura humana y literaria de Sor Juana no había sido consolidada.” Schmidhuber de la Mora observes that, while Schons’s first articles on Sor Juana had been published in the mid to late 1920s, it was not until 1934 that she returned to her Sor Juana scholarship to debunk the notion of some Catholic critics that Sor Juana had somehow given up her studies and “found religion” at the time of her death.

13. Her death certificate cites “a self-inflicted gunshot wound” due to her “extreme nervous condition becoming worse,” saying her body was discovered “32 cal. pistol [placed] at [the] head.” See “Acta de difunción de Dorothy Schons” in the Dorothy Schons Papers, and also Schmidhuber de la Mora, Dorothy Schons: La primera sorjuanista, 14. The certificate is downloadable online.

14. Georgina Sabat-Rivers, “Biografías: Sor Juana vista por Octavio Paz y Dorothy Schons,” Revista Iberoamericana 51, 132–133 (1985): 936–937. Author’s translation. Original text: “Lo más singular de estas dos obras es constatar que Dorothy Schons fue capaz de ver, hace unos cincuenta años, muchas de las cosas que ahora se descubren en Sor Juana. La diferencia de enfoque se basa . . . en la intención expresa de la Profesora Schons de centrar su interpretación en la personalidad de la mujer que fue Sor Juana y explicar sus reacciones dentro de ese contexto. . . . Como mujer, Schons no pudo admitir que Sor Juana se sintiera aterrada y que se doblegara por el miedo como sugiere Paz, porque eso hubiera sido otorgarle al sexo femenino una quiebra fundamental que no se acepta.”

15. Emma Pérez, The Decolonial Imaginary: Writing Chicanas Into History (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999), 6.

16. Ibid., xv.

17. Alicia Gaspar de Alba, “The Sor Juana Chronicles” in [Un]Framing the “Bad Woman”: Sor Juana, Malinche, Coyolxauhqui and Other Rebels with a Cause (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014), 268. Also see “The Politics of Location of La Décima Musa: Prelude to an Interview” and “Interview with Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz” in the same volume.

18. “Hear me with your eyes,” a line from Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Sonnet 211, titled “Que expresan sentimientos de ausente,” in A Sor Juana Anthology, trans. Alan S. Trueblood (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988), 70.