BY DIEGO GODOY

THE YOUNG HIGINIO GRANDA stood soldierly as he faced a mansion on Colón Street in Mexico City. Blond, svelte, and possessing a peninsular accent, he had the ability to pass as a “decent” person. But he was far from it, as his over twenty stints in jail might suggest. “Decent”-looking or not, it made little difference, since he and his swarthier, mestizo associates donned Zapatista military uniforms. The Spaniard looked back at his colleagues and nodded affirmatively before ringing the doorbell. A sharply dressed man named Enrique Pérez cracked open the front door. Granda held up a search warrant and explained that his men needed to scour the residence for arms and other evidence of carrancista support. Pérez scoffed at the suspicion and refused to let the soldiers enter. Granda was not one for violence, but these moneyed elites too often fancied themselves above the law and thus required a little arm-twisting. Francisco Oviedo, Granda’s hard-drinking righthand man, pressed his Lebel revolver against Pérez’s forehead and advised cooperation. The men penetrated the house, intimidated all inside, and stuffed their bags with valuables. Within minutes they departed in their gray Fiat Lancia.

The Gray Automobile Gang’s debut on April, 7, 1915, was a resounding success. They made off with 7,200 pesos, a cache of jewelry worth even more, and a captive whom they eventually cut loose some miles away. Granda must have recalled how just two years earlier he was languishing in Belem Prison. Then came the Decena Trágica. The city was turned upside down, prisons included, and inmates disappeared into the night. A little more than a year later, he would reunite some of his most artful jailhouse acquaintances—a few Mexicans, Spaniards, and a Frenchman—for a business proposal. He argued that his time in the military provided him with resources and connections that could facilitate lucrative, high-level robberies. Convinced, the gang would go on to deprive the capital’s high society of a good night’s sleep for the next few years, while the press waxed eloquent about the criminals’ sophisticated methods and suspected official ties.

In 1919, the capers of Granda and company made the leap from newsprint to celluloid. Recognizing the cinematic potential of the gang’s enterprise, Enrique Rosas directed the silent box-office hit El automóvil gris. The film constituted an early watershed in the history of Mexican cinema. It combined the narrative and visual stylings of French and American crime pictures with a documentary realism best exemplified by its incorporation of the real criminals’ execution footage (Granda and Oviedo excluded).

A Collection for the Cinephile

The glossy, grayscale stills of Rosas’s production available in the Agrasánchez Collection of Mexican Cinema are cinephile eye candy. The Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection houses countless visually arresting items, but for this writer, these movie-related materials are in a class of their own.

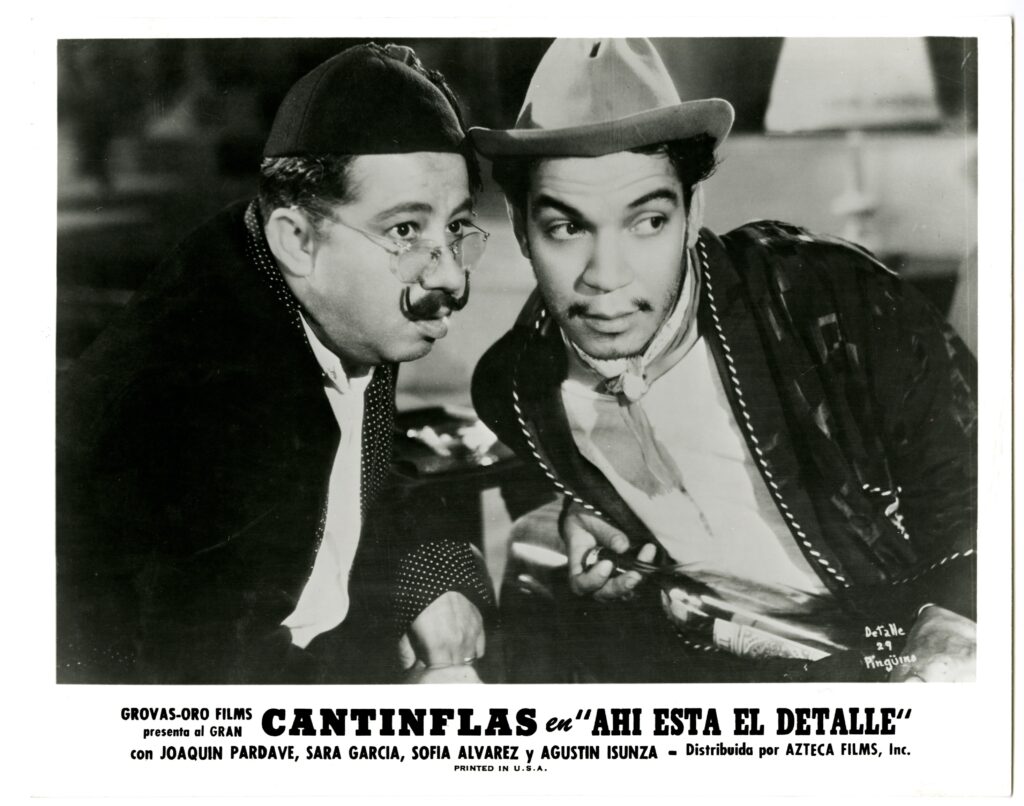

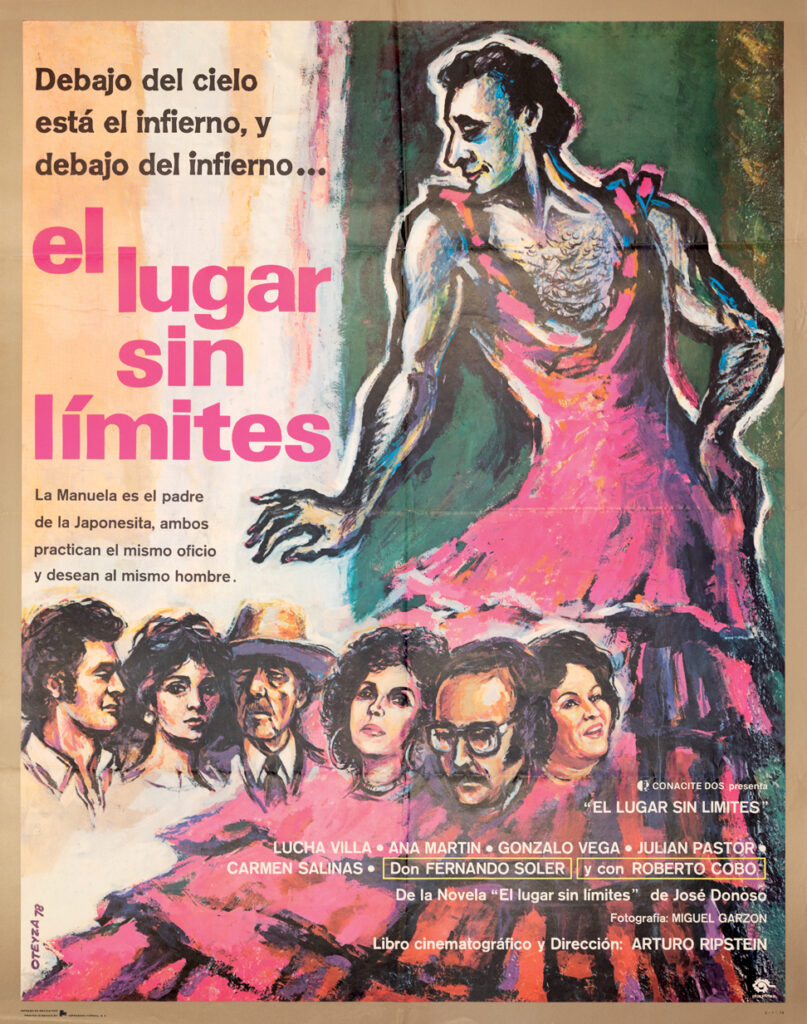

The Agrasánchez Collection consists of 400 movie posters, ranging from comic strip–like drawings on newsprint to multi-photograph compositions on sleek paper; approximately 2,400 lobby cards—small, 11-by-14-inch posters that hung in theater lobbies; and approximately 8,000 8-by-10-inch black-and-white photographs taken on set from 1931 through 1992. Rounding out the archive are VHS tapes and two sets of flyers distributed by Azteca Films, Inc., and Casa-Mohme, Inc., both printed in Spanish and English. All of these items, except the video cassettes, are original promotional materials.

This world-class archive came to the Benson by way of Rogelio Agrasánchez Jr., a collector and scholar of Mexican cinema and the owner of the Agrasánchez Film Archive in Harlingen, Texas—the world’s largest private collection of its kind. It was Rogelio Agrasánchez Sr. who introduced the younger Rogelio to the world of cine mexicano. The elder Agrasánchez worked in movie production and distribution in Mexico and Texas from the 1960s to 1980s. Late in his career, when independent film production in Mexico grew precarious, he took it upon himself to collect and preserve various industry treasures, beginning with film negatives of several classics. He eventually transferred these to video for broadcasting on Spanish-language channels in Texas.

Agrasánchez Jr. watched many of these videos and developed an appreciation for the movies and for his father’s efforts. Then, his brother Julio, an actor in several wrestling films produced by their father, gifted Rogelio Jr. a stack of old movie posters. His poster collection grew over time and he eventually found himself perusing Mexico City archives for additional memorabilia. Unfortunately, the great blaze of 1982 at the Cineteca Nacional reduced thousands of cinematic materials to ashes. But the storied Churubusco Studios contained small mountains of posters, lobby cards, stills, and scripts in their vault—which Rogelio Jr. was able to help himself to—that had been sent there when Azteca Films shut their U.S. offices.

As a PhD student in Latin American Studies at UT, Rogelio Jr. met Dr. Charles Ramírez Berg, a professor in the Department of Radio, Television, and Film, who was looking for sources for a course on Mexican film history. Thankfully for all of us, the latter managed to persuade the former to turn his collection into an archive, and part of it now resides in the rare books stacks of the Benson Collection.

Six Decades of Mexican Cinema

The Agrasánchez Collection of Mexican Cinema mirrors the long sweep of film history in Mexico. Not only can one find stills and lobby cards from El automóvil gris, essentially the first Mexican film, but also stills from Santa (1931), the first Mexican talkie, or movie with a soundtrack.

Unsurprisingly, the so-called Golden Age of Mexican Cinema, or Época de Oro (1933–1964, roughly), is very well represented in the collection. Having commenced quickly after the arrival of sound-on-film technology, this period witnessed unprecedented economic growth and an excess of raw materials and human talent ripe for movie making. In the early 1940s, industry leaders took cues from Hollywood and established large film studios in Mexico City as well as a “star system” built around the top acting icons. Mexico was now the home of the Western Hemisphere’s second-most-robust film business, reaching high levels of production quality, economic success, and serious international acclaim.

The films of the Golden Age were diverse, and no single genre dominated. However, romantic dramas, comedies, and musicals (or rumberas, which featured dancers of Afro-Caribbean rhythms) proved to be crowd-pleasing cash cows. Often, the campo, or countryside, served as the backdrop to these motion pictures, but large, urban settings—usually Mexico City—received their fair share of screen time, too.

The emblematic visages of Pedro Infante, Jorge Negrete, Dolores del Río, María Félix, Pedro Armendáriz, and Mario Moreno, aka Cantinflas, are synonymous with the Golden Age, and their places in the pantheon of silver screen idols are permanent. Although they were known for playing specific character types and marketed as such, a glance at their filmographies reveals admirable degrees of range and versatility.

When José Montelongo, the Benson’s former Head of Collection Development, suggested that I curate an exhibition at the Consulate General of Mexico in Austin using the Agrasánchez Collection, I knew that inclusion of the industry’s nostalgic gems would be obligatory. (An exhibition on cine mexicano sans Cantinflas? Inconceivable.) But I also realized that there was enough gallery space to fully indulge my cinephilic tendencies. I opted to sully the muralistic, romantic nationalism of the Golden Age by also showcasing the darker, subversive offerings of auteurs like Luis Buñuel, Arturo Ripstein, and Felipe Cazals—and, of course, bask in the inevitable gibes about pretentiousness. The end result was titled Seis décadas de cine mexicano (Six Decades of Mexican Cinema) and its inauguration coincided with the first anniversary of CineClub México—an initiative by the consulate to promote Mexican cinema in Austin via monthly film screenings, accompanied by expert commentary, conversation, and alcohol.

Of the aforementioned names, Buñuel, of course, is the one that rings most familiar. One of the most high profile transterrados—to use José Gaos’s term for his fellow Spanish Civil War exiles who settled in Mexico—Luis Buñuel (1900–1983) enjoyed a career spanning two continents, three languages, and five decades. Always the consummate iconoclast, Buñuel created film that dissected religious life, sexual pathology, and bourgeois ideals, often employing surrealist non sequiturs and pitch-black humor as his scalpels of choice. Some of his Mexican output, such as Los olvidados (1950), a social realist tale of defeño street urchins, and El ángel exterminador (1962), an allegorical takedown of the ruling class set in a (literally) confining dinner party, proved to be significant landmarks in Mexican film history.

Internet film lore holds that Arturo Ripstein (b. 1943), the guest of honor at the inauguration of Seis décadas de cine mexicano, got his start as Buñuel’s uncredited assistant director. This is false, but Ripstein does attest to the Spanish auteur’s generosity when the former was a young film student trying to learn something around the latter’s movie sets. With such a cinematic education, it is no wonder that Ripstein made his directorial debut with Tiempo de morir (1966) at the tender age of 21. A Western penned by Gabriel García Márquez, Tiempo de morir was the first in a long series of collaborations with Latin American literary giants, notably Juan Rulfo (El imperio de la fortuna, 1986), José Donoso (El lugar sin límites, 1978), and Vicente Leñero (Cadena perpetua, 1979).

Ripstein’s features have not shied away from delving into the most unsavory depths of Mexican society. From anti-Semitic autos-da-fé, urban criminality, and corruption, to the virulent—and frequently lethal—machismo that infects Mexico, the acclaimed filmmaker’s oeuvre provides a vital and devastating tour of his country’s past and present.

Alongside Ripstein and a handful of other directors who attempted to reinvigorate Mexican cinema during its post–Golden Age stupor is Felipe Cazals (b. 1937). Like his “New Hollywood” counterparts, Cazals did this by upending the established narrative formulas of the studio system and holding up a mirror to his country’s reality. Melodramatic archetypes gave way to complex misfits, morally challenging subjects, and a corrupt and repressive status quo.

Whereas Ripstein has drawn inspiration from historical and contemporary themes, Cazals has focused his camera on particular episodes, both true and tragic, and well within living memory. In 1976 alone, he released three films that tackled cases of ideological manipulation and religious fanaticism (Canoa), sexual slavery enabled by state corruption (Las Poquianchis), and the dehumanizing brutality of the prison system (El apando).

Roberto Gavaldón (1909–1986) and Juan Orol (1897–1988) also made the final cut. The former was the undisputed master of Mexican noir. Traversing town and country, his dramas took on cruel rural caciques (Rosauro Castro, 1950) and cutthroat bourgeois urbanites (En la palma de tu mano, 1951), two distinct subjects not commonly found in a single director’s oeuvre. Demonstrating a blend of technical prowess (evinced by his signature stark back lighting) and sophisticated character development (most typically, troubled protagonists meandering through a troubled world), Gavaldón was a rare filmmaking talent.

Orol, on the other hand, was not. Dubbed the “Mexican Ed Wood” (Wood was called “the worst director of all time”) and often referred to as “The Involuntary Surrealist,” Orol didn’t enjoy the critical acclaim of the aforementioned cineastes. His one-man-band approach to filmmaking—he often starred in, wrote, produced, and directed his pictures—probably accounted for the poverty of many aspects of his productions (for instance, in 1948’s Gangsters contra charros, all the armed men succumbed to a hailstorm of bullets, yet none shed any blood). No matter the case, he found his winning formula: exotic landscapes, cabarets, gangsters, and seductive women (the so-called rumberas), many of whom were played by his Cuban-born filmic muses, notably María Antonieta Pons (1922–2004). Despite the snide criticism and disparaging nicknames, Orol’s films piqued the public’s interest and his status as a cult movie master never waned.

Clearly, I relished digging through this collection and curating an exhibition that would do its holdings (and my personal interests) justice. I know others will, too. These films deserve a wide viewership, and the Agrasánchez Collection of Mexican Cinema deserves to be thoroughly mined by researchers and enthusiasts alike—not only those interested in film history, but also Mexican history, art history, and Spanish, as well as advertising and public relations.

Diego Godoy is a PhD candidate in Latin American history at The University of Texas at Austin. Before coming to Texas, he earned an MA in history from Claremont Graduate University. He is broadly interested in the intellectual and cultural history of the region. His particular focus is on the history of criminology, detection, and crime writing.