BY DANIEL ARBINO

IT WAS INEVITABLE: the scent of fresh cut grass reminded me that we were in the middle of spring in Austin, Texas.1 I was surrounded by green: leaves, lawns, and the lingering light following an afternoon storm. Yet it was not the storm that forced neighbors to stay indoors, leaving the once-bustling city streets devoid of traffic. This was different: new to most of us, but a lesson that history repeats itself in dark ways. COVID-19, like the pandemics before it, changed the way we operated. We became a society of shut-ins overnight.

How do we respond to our new circumstances? Are introverts thriving while extroverts suffer? Did anyone expect to use the word “zoom” so often in their everyday parlance? Subsequently, did anyone expect Zoom fatigue and the compulsory need to prove that you are, in fact, working? When the space where you work and relax becomes one and the same, your well-being is more relevant than ever. Fortunately, the U.S. Latinx Zine and Graphic Novel Collection2 at the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection provides you with the tools to do just that.

While graphic novels have entered mainstream conversation through the success of Marvel and DC films, zines necessitate a brief introduction. Zines, shortened from fanzine, are do-it-yourself publications that have found renewed popularity in the last decade, but originated in the 1930s among science-fiction fans. They are inherently counterculture, reemerging again in the 1970s through the punk scene and the 1990s with feminist nuances. They provide a medium for different groups to cultivate their forms of expression, though this expression ultimately varies depending on the zine creator. Broadly speaking, recurring themes tend to interrogate identity (gender, sexuality, race), place (home, gentrification, nation), and time (childhood, adolescence, adulthood).

For their part, audiences flock to this form of cultural production because zines are affordable, rare, and allow unfettered access to the creator’s perspectives. Such access is significant as many zinesters come from historically marginalized groups that publishing companies have overlooked. Their perspectives tend to undermine mainstream American ideas, and their readership consists of a small, like-minded community. Indeed, most zines are reproduced via photocopier and never reach a circulation over 1,000 readers, but that has not prevented zine fests from emerging across the nation.

To be clear, the following zines are not written about or during the coronavirus, but stem from self-love in the midst of heartbreak, solitude, and rejection. However, their outlook provides an uplifting message for those feeling otherwise downtrodden. While this is only a small sampling of the 250-plus U.S. Latinx zines and graphic novels that the Benson has added since 2017, the mini-comics and zines featured herein are indicative of a hypertext emanating from the collection: inclusivity, self-care, ancestral knowledge, feminist approaches, and self-affirmation.

Agency in Solitude

Home alone. Unable to travel. Nowhere to go. Information regarding COVID-19 changes so quickly that it is overwhelming, and yet it is all anyone talks about. Given these circumstances, it is difficult to maintain a healthy, positive outlook. Rebecca Artemisa’s Curandera Sweetie, described as “a self love/self care spell for sweeties going through a hard time,” uses encouraging affirmation paired with vibrant artwork to spread optimism (etsy.com/shop/RebeccaArtemisa). “Don’t let anyone be loud & wrong at you” and “you are a powerful wildflower” remind readers of their agency while the imagery of spells further enacts it. In both images, the reliance on nature through herbs and flowers suggests notions of olfactory cleansing, that is to say, casting out stale smells and allowing fresh scents to enter. While Artemisa frames aromatherapy as part of traditional knowledge practices like curanderismo, scientific research supports her claim: brain researchers argue that positive emotions, which certain aromas can elicit, have been proven to lower stress levels and improve overall mental outlook (Matsunaga et al. 2011).

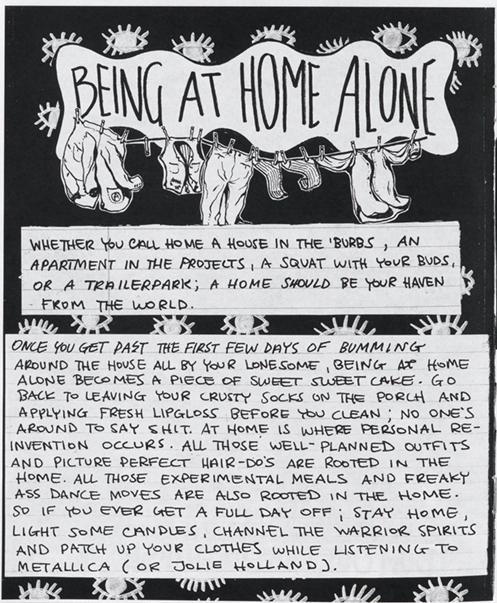

Many of us have had to replace our work environments, often consisting of numerous people, with hours of solitude at home. The abrupt change could be harmful, especially to those people who recharge their energy through social interactions. Julia Arredondo (juliaarredondo.com) explains that Guide to Being Alone “was written in 2012, after enduring several breakups and moving back home post-undergrad. The zine was written in between working multiple minimum wage jobs and a regular schedule of four hours of sleep.” Of course, strategies for being home alone are as relevant as ever in the COVID-19 era. Arredondo shows a socioeconomic sensitivity in her text by equalizing houses, apartments, and trailer parks so that all serve the same function: a “haven” where one can find shelter, safety, and comfort. Later, she prescribes ways to stay busy while growing as a person: reading, playing music, listening to music, and finding time to practice mindfulness. Above all, the author sees home not as a place of stagnation, but rather great self-enrichment: “At home is where personal re-invention occurs.”

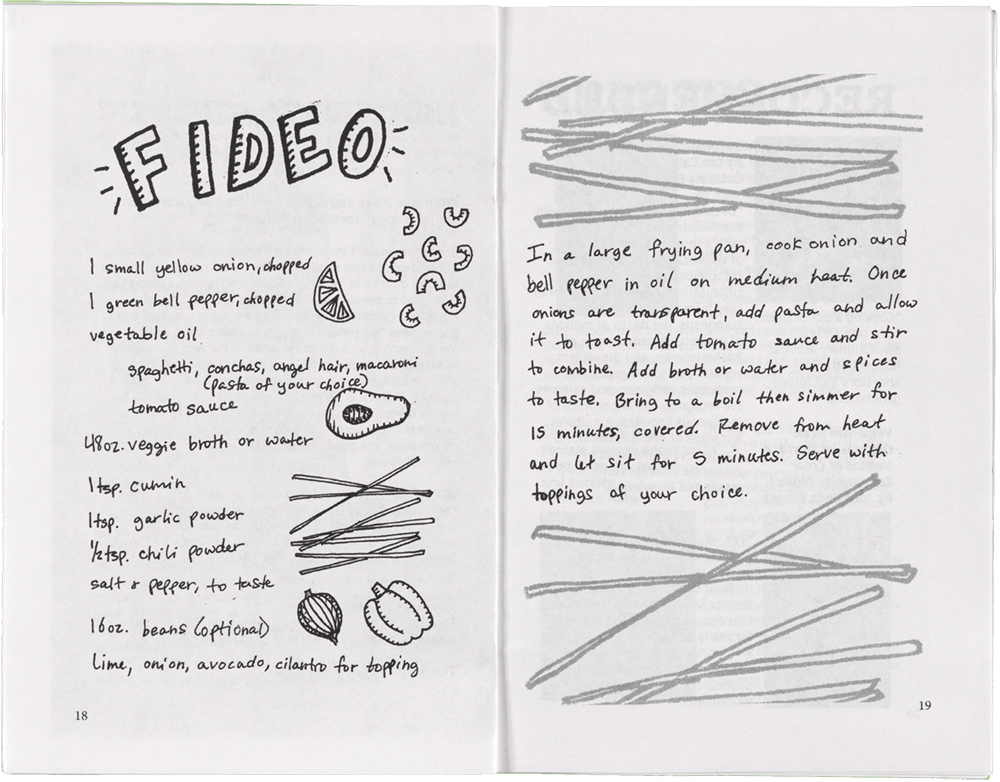

Stephanie Rodriguez (stephguez.com) puts forth a similar idea in How to Mend a Broken Heart (2016), a mini-comic meant to give readers a list of activities to keep them from thinking of heartbreak. Rodriguez’s work implores the reader to “reverse the sadness” by expelling energy via workouts. She also declares the necessity of learning to have fun alone, and in her mini-comic, the protagonist is seen reveling in a homemade meal. The scarce amount of flour in grocery stores suggests that the coronavirus has presented many of us with the opportunity to make our own meals, perhaps exploring new recipes in the process. Zines at the Benson, such as Suzy González’s Xicana Vegan, are rife with recipes (suzygonzalez.com). In short, staying active while at home is a useful way to foster personal growth and self-discovery without being bogged down with the realization that everything is closed.

Self-Love Realized

The time spent indoors will ultimately lead to a deeper understanding of who we are as individuals. Again, we might turn to zinesters who have used their creative outlet to workshop their sense of self. In La Horchata (2018, instagram.com/lahorchatazine), Ashley Sanchez-Garcia articulates the importance of self-love in the poem “spring,” when she ends in three declarative statements: “today I will worship myself. I will provide myself with love. / every color in the world was made for my skin.” Reza Moreno’s similarly themed poem of self-honor adds an inflection regarding race. In “My Latina Roots,” she describes herself as “A woman of passion and color / one with curves right on my body / thick, curly hair as you see / one who is not afraid to tell and put her foot down.” Whereas Sanchez-Garcia does not allude to feelings of inferiority, Moreno’s contribution to Mujeristas Collective (mujeristascollective.com) uses her childhood shame to propel her trajectory as a proud Mexican woman and leader.

Pride in one’s heritage is a recurring premise in Latinx DIY publications. Kat Fajardo’s autobiographical mini-comic Gringa! (2015) expresses “years of personal struggle with cultural identity through assimilation, racism, and fetishization of Latin culture as an American Latina” (katfajardo.com) The daughter of Honduran and Colombian immigrants, Fajardo details how embracing her parents’ immigrant story became a source of pride. The protagonist’s coming of age has gone hand in hand with her mounting interest in her cultural upbringing. She concludes her narrative with affirmation: “Half Honduran, Half Colombian, damn proud of it.”

A final example, Anel Flores’s (anelflores.com) “Looked for Myself in SA: Cesar Chavez Blvd” in St. Sucia XIV (2019), shows the intersectionality of gender, race, and sexuality when the poetic voice finds comfort in a pachuco-style suit. In that suit lies promise for further self-discovery: “I saw a costume I might fit into / a body I’d maybe finally warm up in / a gender blend / a pachuco femme.” Of note is the immediate acceptance from Matthew, the salesperson whose warmth provides the welcoming space for the poetic voice to feel “a tinge of brand new.” These moments of kindness remind us of what a post-COVID-19 world can be.

As we continue to navigate these difficult times, take a moment to reflect on who you are and who you want to be, and let us try to be better than we were a year ago. And after we have survived this and it comes to an end, for it will, visit the Benson. We have a U.S. Latinx zine and graphic novel collection that will surely entertain you.

Daniel Arbino is the head of collection development at the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, The University of Texas at Austin. He specializes in U.S. Latina/o and Caribbean literature, and his most recent publications can be found in Aztlán, Chiricú, and eTropic. He graduated with a PhD in Latin American literature and culture from the University of Minnesota (2013).

Notes

1. The first lines of this piece, as well as the title, were inspired by Gabriel García Márquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera (1985).

2. U.S. Latinx Zine and Graphic Novel Collection

References

Arredondo, Julia. Guide to Being Alone. 2012.

Artemisa, Rebecca. Curandera Sweetie.

Fajardo, Kat. Gringa! 2015.

Flores, Anel I. “Looked for Myself in SA: Cesar Chavez Blvd.” St. Sucia XIV: Soy. Ed. Isabel Ann Castro and Natasha I. Hernandez, 2019. stsucia.bigcartel.com.

González, Suzy. Xicana Vegan No. 1.

Matsunaga, M. et al. “Psychological and Physiological Responses to Odor-Evoked Autobiographic Memory.” Activitas Nervosa Superior Rediviva 53,3 (2011): 114–120. Semantic Scholar [Online]. Available at: rediviva.sav.sk/53i3/114.pdf

Moreno, Reza. “My Latina Roots.” Mujeristas Collective No. 1.

Rodriguez, Stephanie. How to Mend a Broken Heart. 2016.

Sanchez-Garcia, Ashley. “spring.” La Horchata Arts Magazine: Primavera 2018. Ed. Veronica Melendez and Kimberly Benavides. 2018.