BY MATTHEW BUTLER and JOHN ERARD

THE ROADS TO MICHOACÁN: MATTHEW BUTLER

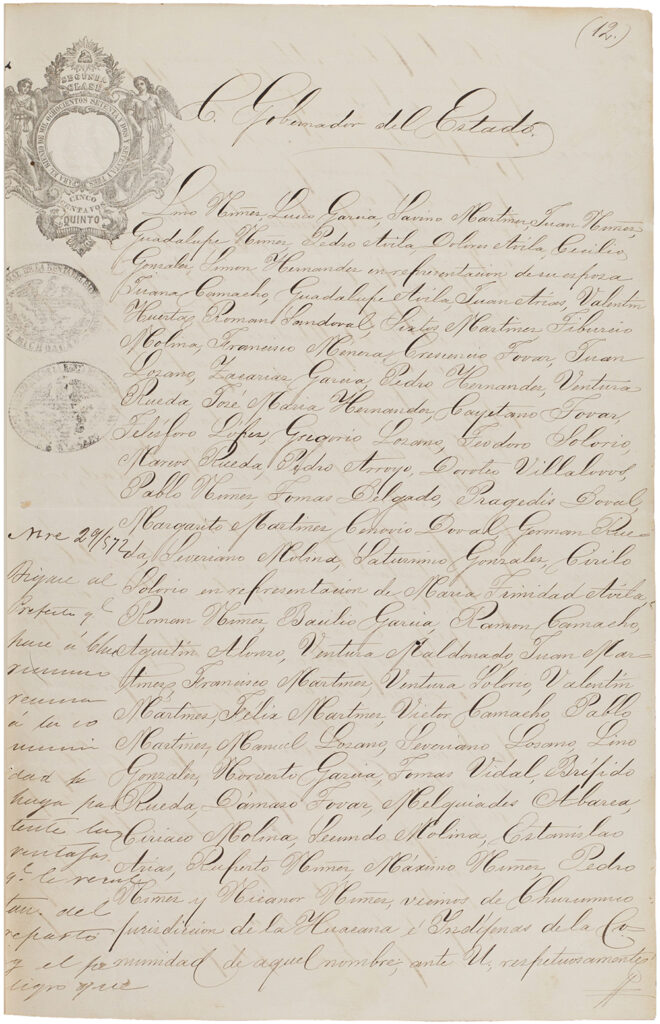

IT IS SAID that the history of a Mexican pueblo is the history of its lands. What better way, then, to explore that history than through land records such as Michoacán’s hijuelas books? I first came across these nineteenth-century deedbooks––46,000 beautiful, handwritten folios in 190 leather-bound volumes––when researching the backstories of indigenous communities that fought in the 1920s cristero rebellion. The hijuelas record an earlier process: the privatization of common lands belonging to hundreds of pueblos in the western state of Michoacán from the early 1800s through the 1920s. More than notarizing agrarian subdivisions, these documents tell us how indigenous people navigated the transition to private property and citizenship under the Mexican republic, and how this process changed their lives, politics, and ideas of community. The collection is also invaluable because it records the experience for all five groups of indigenous michoacanos: Purépecha, Otomí, Mazahua, Nahua, and Matlatzinca.

With two Mexican colleagues and a former PhD student now working in Texas’s General Land Office, I devised a project to digitize the hijuelas, given their exceptional historical importance and fragile, bug-infested condition. Thanks to a British Library Endangered Archives Programme (EAP) grant, the digitized books––all 95,000 images––have just been uploaded to the EAP website, where they can be freely accessed.1 We hope they will be sought not just by historians but by the diaspora of michoacanos who are interested in exploring their roots and by members of Michoacán’s indigenous communities, which in recent years have begun to reassert an autonomous juridical identity in line with their historic “usages and customs” (usos y costumbres). There they will hear, as in no other source, nineteenth- and early twentieth-century indigenous voices talking (sometimes fighting) over who, what, and where the pueblo was.2

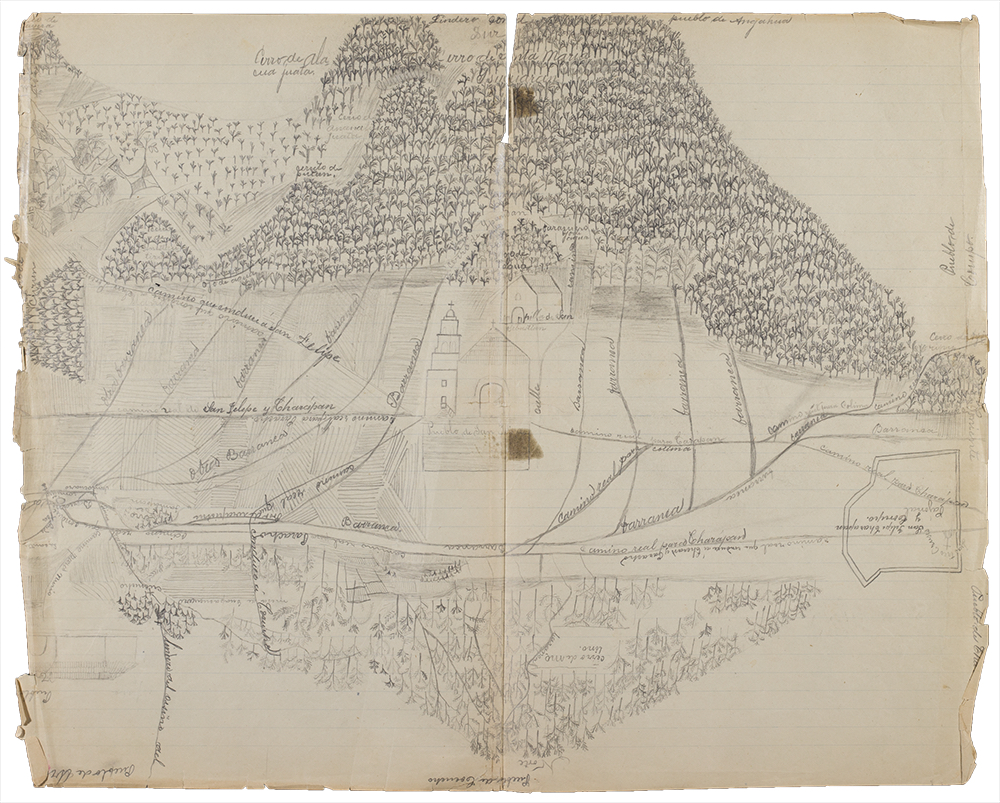

Here we only need look at the hijuelas of Churumuco, a farming and fishing community hidden behind the Jorullo volcano and nestled on the Balsas River separating Michoacán from Guerrero State. Defended by fumaroles and its surging river, Churumuco retained its lands in 1868, about half lying over the state line in Guerrero. The land division was promoted by Donato Orozco, a wealthy indigenous representative (apoderado) who rented Churumuco lands to mestizo ranchers. Yet Orozco’s account-keeping was murky, people alleged. Rents disappeared, except for money splashed on “useless things, like fireworks, rockets, and dances.”

Subsequently, the hijuelas record a twenty-year struggle involving not only land but incompatible concepts of pueblo and intergenerational conflict. Was the pueblo a patriarchy in which elite Purépechas administered land and labor for the government? Was something more democratic possible? Gender conflicts were folded in: with the controversial land division finally enacted (1878), all 250 Michoacán lots went to ex-comuneros (“members of the ex-community”) supporting Orozco. The Guerrero plots went to self-identifying indígenas (“indigenous people”) led by María Teresa Camacho. During the 1880s, she organized land invasions and demanded a new survey using an older, 1851 law, because, she told Michoacán’s governor, “we are tired of tolerance and suffering.” Indígenas’ “exasperated spirits” had been tested beyond the breaking point by their opponents’ “injustices.” Camacho’s rebellion was multiethnic: government spies in the 1890s reported alliances with Nahua villages in Guerrero and the Matlatzinca pueblo of Huetamo 70 miles away. In 1902, finally, Churumuco’s indígenas succeeded in having their lands resurveyed—bringing us to the eve of the Mexican Revolution.

Churumuco’s story, with its indigenous feminist heroine, is one of hundreds in the hijuelas. Although a snapshot, it is vividly removed from downtrodden indigenous histories of people passively victimized by liberal states. Instead, we see an indigenous resurgence, younger indígenas doubling down on a self-consciously ethnic identity and showing awareness of politics and different legal codes, their goal to steer liberal reforms and overthrow a conservative pueblo elite.

An International Collaboration

One rewarding aspect of the project is the way it has created its own kind of community, linking students from Michoacán and Texas, librarians and archivists in three countries, Michoacán’s state government, three research universities, and a group of twenty researchers from Mexico, the United States, the UK, France, and Germany (the latter will conference the material in May 2021). That this was possible is very largely due to LLILAS Benson’s post-custodial archiving3 expertise, its regional outreach and recognition, and its strong commitment to the projection of indigenous memory beyond the physical archive through the use of digital methods.

To kickstart the two-year project, LLILAS Benson forged institutional relationships with the British Library, Michoacán’s Interior Ministry and state university, and deepened its relationship with Mexico’s Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social (CIESAS). This explains how a grant in sterling could be used by a Texas-based project to hire four students in Michoacán in compliance with Mexican labor law and to tender for digitization equipment in Mexico City.

In late 2016, LLILAS Benson post-custodial archivist Theresa Polk and digital processing archivist David Bliss spent a week in Morelia, Michoacán’s state capital, training our project hires in digitization and metadata creation techniques. The Michoacán Interior Ministry, as custodian of the hijuelas books, kindly conditioned a large workspace in the Governor’s Palace, an eighteenth-century ex-convent. Polk, who now heads LLILAS Benson digital initiatives, and Bliss led a similar workshop for the state archive’s permanent staff, drafted digitization workflows in Spanish, and performed quality controls on the resulting images.

LLILAS Benson has also helped to create digital discovery tools that make the material accessible to researchers, such as document-level, text-searchable metadata, meaning a detailed, descriptive database that makes it possible to navigate the collection using individual search terms. We purposefully recruited graduating history students from Michoacán’s state university who had the language, paleography, and historical skills to read the documents and create a detailed, descriptive finding aid. This greatly expands the functionality of the digital collection by allowing users to apply diverse filters to refine search results. These tools will allow users to research across the hijuelas far more easily than would be possible with the physical collection, for example, viewing all land titles recorded across all municipalities in Michoacán within a given year, or in relation to a given community. Digitization thus not only preserves the hijuelas books from physical decay, it enhances their informational value by allowing users to dynamically recontextualize each document according to their specific research interests. In the near future, LLILAS Benson plans to upload project metadata to its Latin American Digital Initiatives (LADI) portal (ladi.lib.utexas.edu).

In addition to showcasing LLILAS Benson’s support for digital archiving and institutional partnerships with the Mexican academy, the project relies on faculty-undergraduate research collaborations. The latest in the line of students who have contributed to the project is my co-author, Undergraduate Research Apprentice John Erard.

MAPPING THE ARCHIVE: JOHN ERARD

MICHOACÁN, “the place of the fisherman,” has always been a region marked by exceptions in my mind. Derived from Nahuatl, its name conjures images of Lake Pátzcuaro and an aqueous horizon of flitting, butterfly-shaped fishing nets—the rich and distinctive heritage of the Purépecha. Purépecha, a language isolate, has stubbornly resisted easy linguistic categorization in much the same way that its pre-Hispanic speakers successfully resisted political incorporation by the Nahuatl-speaking Mexica. That spirit of defiance is littered throughout Michoacán’s history, and is often presented as a point of exception. Mexico has Malintzin, Michoacán has Eréndira.4

While physically located on Mexico’s periphery, Michoacán has been no small player in Mexico’s history. José María Morelos, after whom the capital of Morelia is named, was an important figure in Mexico’s War for Independence; michoacano Lázaro Cárdenas del Río was the president (1934–1940) who stood tallest among those engaged in post-revolutionary agrarian reform.

It was this sense of exceptionalism that led me to grasp the value of the hijuelas books as objects of historical inquiry. Though far from monolithic, land privatization was experienced all over Mexico during the mid-nineteenth century. The hijuelas documents, however, are unrivaled in their completeness and make Michoacán a uniquely good case study.

Visualizing the Reparto de Tierras

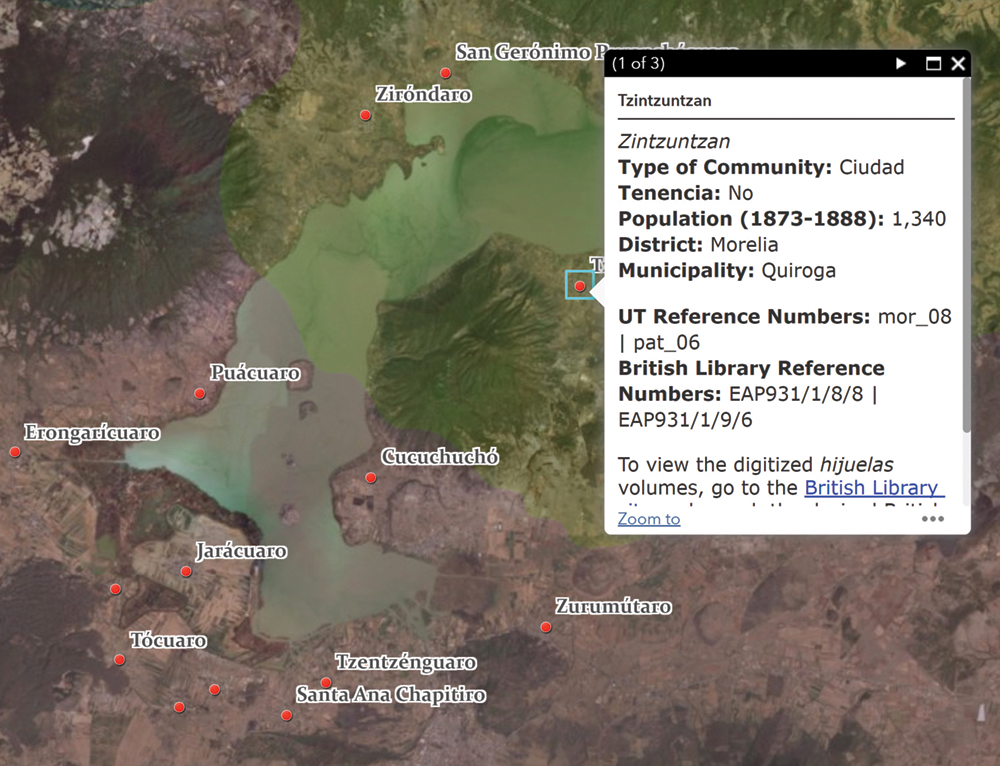

Given the potential impact that these documents would have on historians’ understanding of Mexican indigenous history, as well as the state’s complex agrarian history, I wanted to attach myself to the project in any way I could. My early meetings with Dr. Matthew Butler at the Department of History were punctuated by palpable excitement and a strong feeling of gratitude. After all, I was getting the opportunity to work with history, my passion, in a far more concrete way during my freshman year than I would have ever imagined for myself. Dr. Butler told me that my primary role in the collaborative, international research effort was to map the 228 communities that participated in the nineteenth-century privatization of indigenous land (officially, the reparto de tierras.) Tools of the nascent field of spatial history would eventually help me to produce a web-hosted map to aid in future research around the hijuelas documents.

In taking the torch from my michoacano counterparts, I used a table listing the names of the hijuelas communities collated by the digitization team as a jumping-off point for my own stage of the project. Armed with funding and class credit from the Undergraduate Research Apprenticeship Program, I began to work on my set task of displaying the reparto spatially. Before the cartographic work could begin, I needed to compile the data that would constitute the meat and bones of the digital object. The land privatization process needed to be understood in its specifics before it could be figuratively and literally drawn.

Primary research in nineteenth-century geographical dictionaries and statistical informes indicated the number of individuals affected by the reform, while the 1895 census and an 1865 parish ethnography by Father José Romero illuminated dimensions of indigeneity and gender. Population and location data were obtained for communities as small as thirty persons, affording the clearest picture yet of the form and size of the reparto.

The archival research allowed for the creation of a core data set that would contain all the information gathered on the hijuelas communities as organized by their nineteenth-century political divisions (elucidated by the earlier research process.) The murky nature of the historical reform was thus translated into the unambiguous language of cartographic software, yielding long tables of data.

Once the core data set was finalized, the more technical, cartographic phase could begin. I employed geographical information system (GIS) software to create an interactive map that could be manipulated by the user in several revealing ways. Using both the open-source QGIS and the proprietary ArcGIS Pro, I geocoded the location data of hijuelas communities in longitude and latitude, and layered that on top of the period-accurate district boundaries—drawn using geospatial data gleaned from georeferenced nineteenth-century maps.5

Not only does the resulting map6 provide an intuitive way to navigate the population and other attribute data of individual communities, it will allow for new inquiries into how physical geography, hydrological resources, and other environmental factors impacted the hijuelas reform. For those hoping to consult the digitized collection on the British Library’s website, the map will help to organize the collection.

I have seen firsthand how cartography turns space into place. Transforming the empty white canvas on a computer screen into a coherent medley of verdant patches of green, translucent bends of blue, and rusty ranges of burnt umber, I encountered the beauty and historical significance of Michoacán anew.

Matthew Butler is associate professor of the history of modern Mexico at The University of Texas at Austin and is director of the Hijuelas Project. He has written and published widely on Mexican agrarian and religious history, with special emphasis on Michoacán.

John Erard is a second-year undergraduate at The University of Texas at Austin. He studies history and geography along with participating in the Liberal Arts Honors Program. His interests lie in the history of Latin America, the spatial humanities, and the use of digital tools in historical research.

Notes

1. “Conserving Indigenous Memories of Land Privatization in Mexico: Michoacán’s Libros de Hijuelas, 1719–1929.” doi.org/10.15130/EAP931. Co-PIs: Antonio Escobar (CIESAS), Cecilia Bautista (UMSNH), Brian Stauffer (GLO).

2. For more information, see Matthew Butler and David Bliss, “Digital Resources: The Hijuelas Collection,” Oxford Research Encylopedia of Latin American History. Available at latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com. DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.618.

3. Post-custodial archiving is a process whereby sometimes vulnerable archives are preserved digitally and the digital versions made accessible worldwide, thus increasing access to the materials while ensuring they remain in the custody and care of their community of origin.

4. Malintzin, also known as La Malinche or by her Spanish name, Doña Marina, was a Nahua translator and culture broker for conquistador Hernán Cortés during the Spanish-Aztec war of 1519–21. Eréndira, a Purépecha princess who was said to have militarily resisted Spanish colonization, is often put in opposition to Malintzin for their differing roles during the Spanish arrival.

5. Georeferencing is a digital process whereby real-world geospatial coordinates are assigned to various points on a map or aerial image. The georeferenced map or image can then be used by geospatial software.

6. This map will be visible alongside the metadata on the LADI page.