BY JULIA DETCHON

IN THE FALL OF 1945, gathered at the Buenos Aires homes of the psychoanalyst Enrique Pichón-Rivière and the photographer Grete Stern, a group of Argentine artists hatched an idea for a new movement based on abstract principles of painting. Under the name Arte Madí, they declared their commitment—in pamphlets, manifestos, and exhibitions—to expressing the reality of modern life not by attempting to mimic it but by inventing it through art. For artists such as Gyula Kosice and Tomás Maldonado, these ideas took the form of playful, geometric compositions. The canvas should not be an illusionistic or fictional representation of the world, they argued, but a part of the world, a “concrete” object in space that refers only to itself. Though Maldonado, Kosice, and likeminded artists splintered and subdivided into several groups over the following decades, this revolutionary idea—that art should be freed from any symbolic or referential meaning—became the defining characteristic of Concrete art, a highly influential set of aesthetic principles throughout Latin America in the twentieth century.

The Concrete Poetry Collection,1 a small archive in the Benson’s Rare Books and Manuscripts Collection, tracks the flourishing of Concrete art in Argentina, from its origins in Grupo Madí’s exhibitions to its more experimental applications beyond painting in the 1960s and 1970s. As the formal experimentation of Concrete painting spread, particularly in Brazil and Venezuela in addition to Argentina, its practitioners found counterparts in the literary world. Like Concrete artists, Concrete poets pushed text beyond any indexical relationship to the real world, arguing that it should exist simply as form. By 1952, the Brazilian poets and brothers Augusto and Haroldo de Campos had, with Décio Pignatari, formed the pioneering Noigandres2 group in São Paulo, publishing the principles of Concrete poetry in Brazilian newspapers and magazines. Many Concrete poets and artists connected their compositions with the rapid modernization that came with Latin America’s postwar industrial boom, which brought with it new institutions of modern art. Indeed, “visual poems” were often displayed alongside abstract paintings in these new institutions, as in the 1956 National Exhibition of Concrete Art at São Paulo’s relatively new Museum of Modern Art. The close ties between the Noigandres poets and the Concrete art movement in São Paulo illustrate the degree to which the prevailing theories of abstraction—of language and visual form—spanned not only painting and sculpture but also literature and music.

In the second half of the twentieth century, the theories of Concrete art and Concrete poetry intertwined through radical experiments with language. Led by pioneering figures such as Edgardo Antonio Vigo in Argentina, artists formed and participated in international networks of creative exchange, proposing participatory and collaborative relations between artists and their publics. The Benson’s Concrete Poetry Collection thus sketches an important history of the transition from Concrete art to Conceptual art in Latin America by documenting the eroding distinctions between art and everyday life.

From the Canvas to the Page

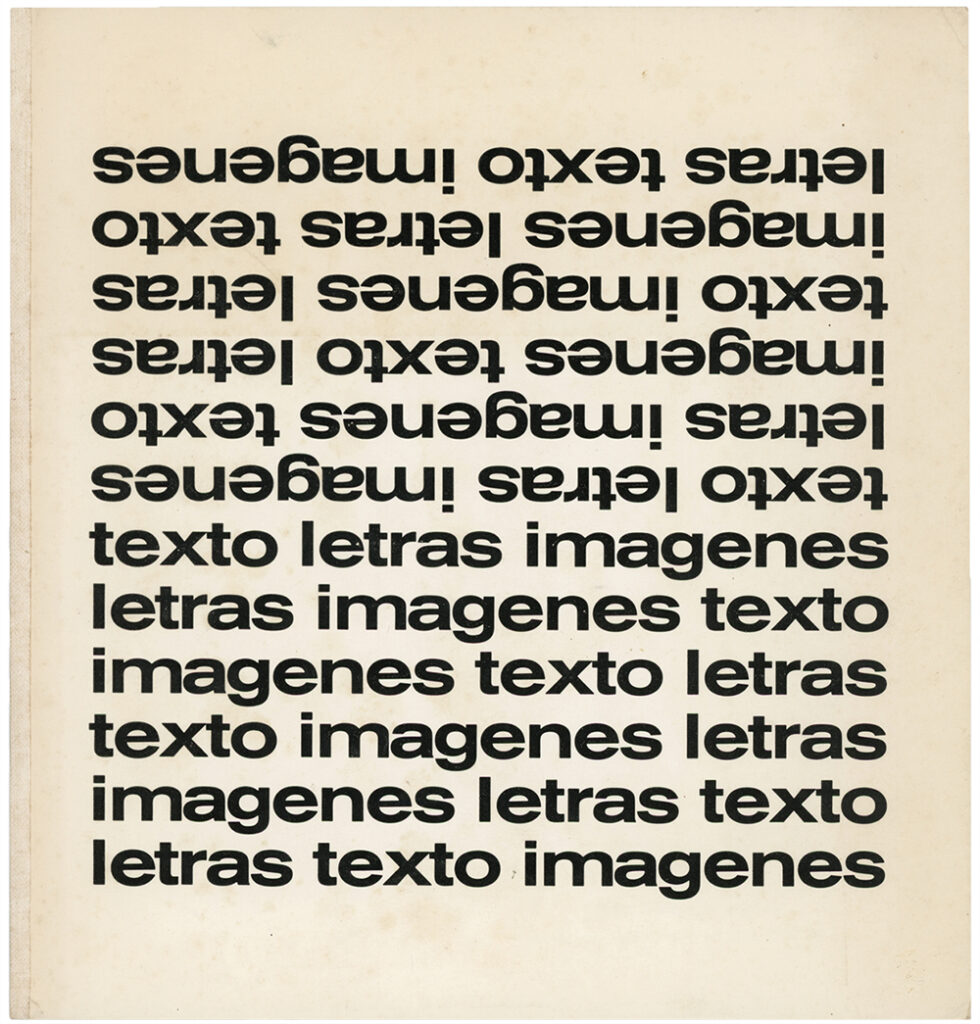

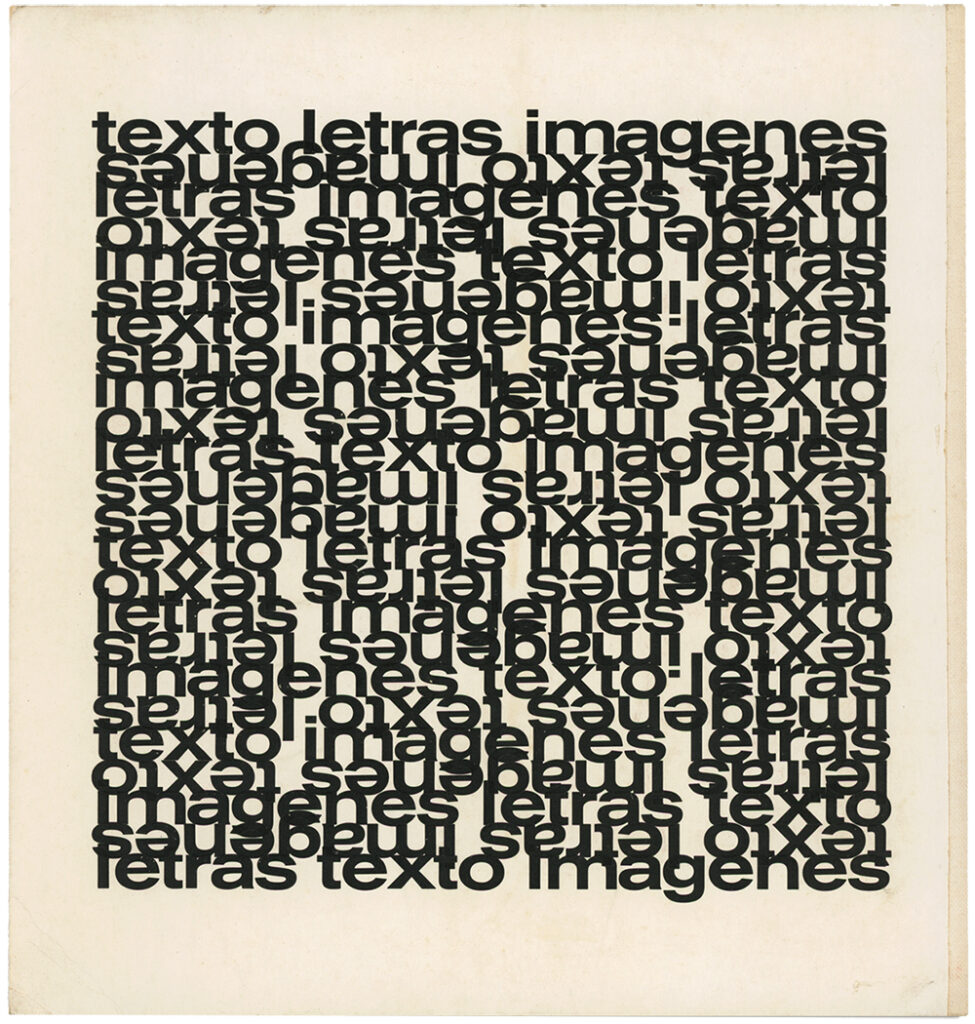

According to Augusto de Campos, a Concrete poem was “the tension of word-things in space-time,” text moved off the page and into space. Like a Concrete painting, a Concrete poem does not unfold in a narrative, but presents itself as its own discrete reality. Both captured the directness of modern communication, as economical as a billboard, a poster, or an advertising slogan. The Bolivian-German poet Eugen Gomringer’s book Texto Letras Imágenes, for example, blurs the line between aesthetic and literary composition by experimenting with typography as if it were elements of drawing. Originally the catalogue for a 1967 Concrete poetry exhibition in Spain, Texto Letras Imágenes brought together contributions from German poets and painters. It also documented the experimental networks that formed among Concrete artists and poets around the world, linking groups like Madí and Noigandres with Beat writers in North America and Fluxus artists in Europe—networks that took shape in exhibitions and literary magazines. (Below: Eugen Gomringer and Reinhard Döhl, Exposicion: texto letras imágenes. Institutos alemanes en españa. Stuttgart, Germany, 1967–1968.)

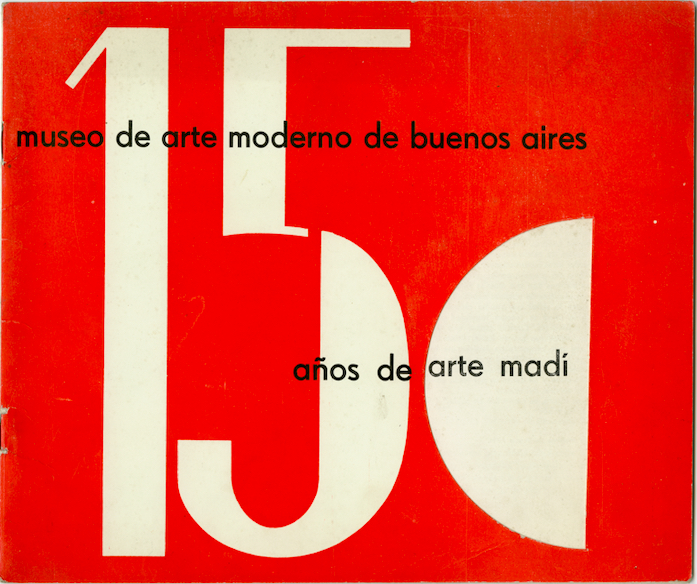

Tucked in the Benson’s collection is the tiny gem Piumo, one such literary magazine published in 1964 by Juan Carlos Kreimer and the little-known Grupo Opium, young Beatniks who formed part of an Argentine literary scene sometimes called “el Swinging Pampa” or the “Buenos Aires Beat.” Though the magazine was short-lived, this edition includes a modest drawing by the aforementioned Edgardo Antonio Vigo, one of the most prolific practitioners of both visual art and visual poetry in Argentina and a central node in these networks of exchange. Vigo, who maintained a decidedly provincial practice in his hometown of La Plata, Argentina, was nonetheless intimately involved in many of the intersecting groups that consolidated around the “new tendencies” of Concrete art and poetry. In 1962, he had formed his own group, Grupo Integración, comprised of Madí artists Guillermo Adolfo Gutiérrez and Beatriz Lilia Herrera, and the Brazilian poet Antonio Miranda, who used the pseudonym Da Nirham Eros. By 1962, the Madí group had been given a 15-year retrospective at Buenos Aires’s Museum of Modern Art; the innovations of Concrete art had, in many ways, been institutionalized; and it was now up to a younger generation to take up its spirit of experimentation.

Off the Page and Into the World

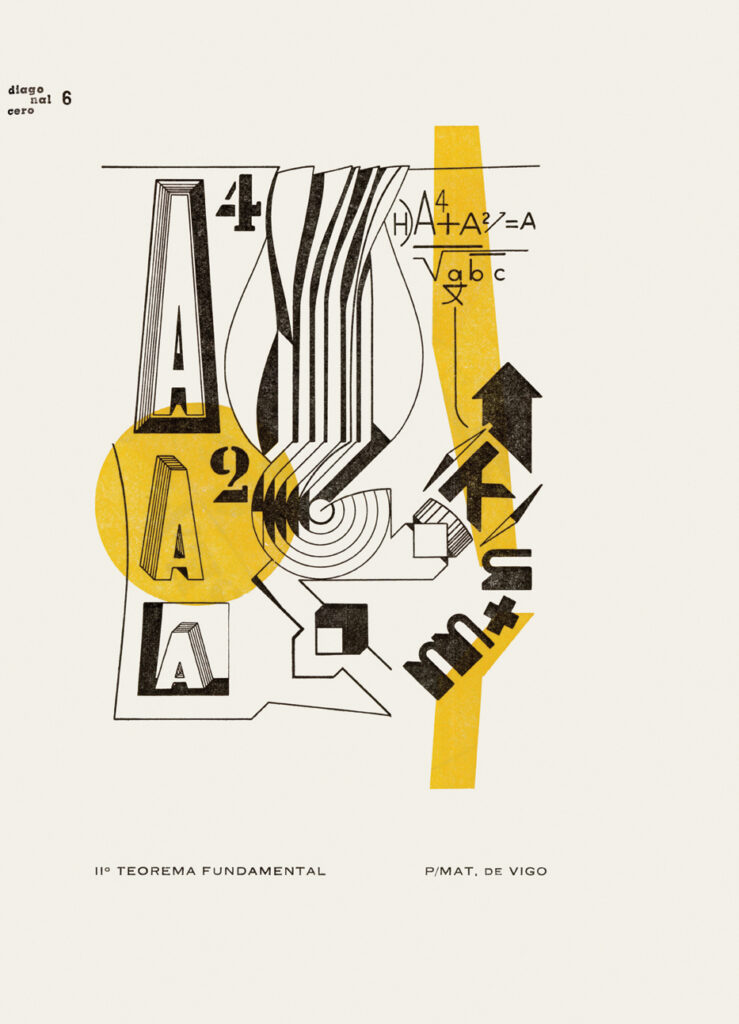

Vigo brought together the original figures and new practitioners of Concrete art and poetry in his influential magazine Diagonal Cero,3 which circulated work from Latin America and Europe between the years 1962 and 1969. Across its 25 issues, Vigo pushed the limits of the magazine format, developing a strong editorial and graphic style that emphasized playful experimentation: unbound, irregular, and folded pages; a range of colors and typographies; original woodcuts; and instructions for possible works of art.

Diagonal Cero explored the forms and materiality of letters and words through visual, mathematical, phonetic, sonorous, interactive, electronic, and virtual texts. In issue 3, for example, an article on Madí follows a short essay by Herrera on the work of Da Nirham Eros (Miranda). Herrera’s essay unfolds into Miranda’s visual poem “CAISNAVIOMAR,” presented in the form of three translucent sheets with a hole cut out to reveal different textual combinations of the three words contained in the title. Herrera writes, “upon lifting the first leaf (a temporal action), we move away from the pier [cais]; the departure has occurred, leaving the NAVIO [boat] at sea. A new action, and the NAVIO, passing beyond the horizon line, disappears from our sight, leaving only the SEA [mar]. The reader has now been incorporated into the poem. He has lived it.” Miranda’s poem is a temporal and spatial experience recalling Augusto de Campos’s “tension of word-things in space-time.” More importantly, it reveals reading to be a participatory activity that relies on the body rather than passive contemplation.

Later issues of Diagonal Cero push this idea further, proposing that a poem could be worn on the body or circulate as an object. In issue 20, Luis Pazos, a frequent collaborator on the magazine, published the essay “Phonetic Pop Sound,” in which he suggests that poetry is something that happens in material space rather than on a page. He writes,

Poetry is a fact that happens in the outside world. Its material is the neon signs, the honks, the chatter of the people, the shop windows. It has nothing to do with beauty, but rather with speed, with a poorly digested lunch, with a wrinkled suit, with discomfort. It is a fact that happens in the city, at every moment and to anyone. (Author’s translation)

If a Concrete poem can take the form of a written word on a page, a feeling in the mouth, or a sound in space, then Pazos expands its communicative potential at least to include noble gases and a “poorly digested lunch.” As in Miranda’s poem, the reader has become a participant in the poem: she has lived it.

Throughout the magazine’s run, the line between visual poem and artwork became increasingly blurred as it asked readers to seize on the generative potential of its contents. This radical use of text took the form of action-based works, such as wearing a poem on the body, and circulatory works, such as mail art. These works all relied on the idea that the public activates—and thus produces—a work of art together with the artist.

Diagonal Cero’s final issue closes with a hole at the center of the last page, accompanied by nothing except a sparse set of instructions to “Concrete su poema”: “[Make] concrete your visual poem / painting / object / sculpture / landscape / still life / nude / (self) portrait / interior or any other type or genre of art. HOW TO USE: place the hole at a prudent distance in front of one eye and frame, in full freedom, the genre desired.” Here, the “poem” has become an open work, something left entirely in the hands of the reader to unfold in real time. It is a fitting end to the run of the magazine, the logical conclusion of Vigo’s ever-expanding view of poetry and the sublimation of art into life.

“Concrete su poema” is perhaps the best embodiment of an ethic that defines not only the contents and methods of Diagonal Cero, but all of Vigo’s heterogeneous output. It mirrors the proposal of his Obras (In)completas, a set of four lithographs tucked into the back of a group exhibition catalogue, which invite recipients to affix the labels to anything they consider worthy of art status. Vigo’s own response was to put the labels on earthenware bottles of Bols gin (often advertised as “the traditional drink of Argentine gauchos”). He explained, “YOU choose the object you want to turn into my incomplete works. I just happened to choose four bottles . . . they could just as well have been boxes or walls or anything else. . . . All I give are the labels. The rest is entirely up to you.”4 For Vigo, a work of art was not a finished product, or even a discrete object at all, but a site of generative possibility and exchange. Relying on the participation of a viewer or receiver to be completed and to circulate in the world, it shifts the relationship between artist and viewer from a didactic one to a collaborative one.

Ultimately, it is the openness of the Concrete approach to abstraction—the idea that a work of art or literature organizes its own reality, and can do so an infinite number of times—that is the lasting legacy of Concrete art. In 1971, Vigo participated, with fellow poet Elena Pelli and several other Argentine artists, in an exhibition devoted entirely to proposals for uncompleted works. Paradoxically, the initial denial of an indexical relationship between text/image and the “real” world had, over the years, opened up to encompass the entire world as art. In a letter inviting the Fluxus artist Dick Higgins to participate, Pelli explained that one goal of the exhibition was the transcendence of poetry and the complete integration of a “total art.” “As you know,” Higgins replied, “I’ve been a worker in the Happenings/Fluxus/Concept Art continuum since 1957–58, so I feel no obligation to make Art per se.” For artists like Vigo and Higgins, in the years since, art had become poetry had become art again. Which is to say, there was no difference between art and life.

Julia Detchon is a PhD candidate in the art history department’s Center for Latin American Visual Studies. Her research focuses on modern and contemporary Latin American art with an emphasis on networks of conceptualism. Her dissertation, on four women artists working in Buenos Aires in the 1970s, has been supported by the Social Science Research Council, the Fulbright U.S. Student Program, and the Tinker Foundation. From 2016 to 2018 she was the Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in Latin American Art at the Blanton Museum.

Notes

1. See legacy.lib.utexas.edu/taro/utlac/00438/00438-P.html.

2. See, for example, Antologia Noigandres: do verso à poesia concreta 5 (1962), a copy of which is held by the Harry Ransom Center.

3. Diagonal Cero, nos. 1–28 (1962–1968), Rare Books and Manuscripts Collection, Benson Latin American Collection.

4.. Hugh Fox, “Edgardo Antonio Vigo: Argentinian Graphics Experimentalist,” The Pan American Review 1, no. 1 (Winter 1970–71): 35–42. Available at the Harry Ransom Center.