By FERNANDO LUIZ LARA

IN JUNE OF 2013, over forty UT Austin faculty members and a similar number of Brazilian officials met in the halls of Congress in Brasília, celebrating the signing of agreements and research partnerships. The future looked so bright then, and I remember stressing the importance of that moment that I shared with colleagues from six different UT colleges, joined by then-President Bill Powers, representatives of Brazil’s Senate, Supreme Court, and Ministry of Education, all of us coming together to fund research collaborations. One week later, Brazilian cities exploded in protest, and we are still trying to understand June 2013 and its aftermaths: the legislative coup against Dilma Rousseff in 2016 and the election of Jair Bolsonaro in 2018. The photograph that opens this short essay shows protesters on the roof of the Brazilian Congress, exactly above the room where we had met a week before.

It has only been nine years since that visit, but it feels like half a century has passed. In October 2022, the Brazilian people will have a chance to vote and maybe start on the long path toward healing the damage inflicted on Brazil during the last six years. This time, there will be no Sergio Moro breaking all kinds of laws and procedures to jail frontrunner candidate Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, only to be rewarded with the Ministry of Justice (Attorney General) in the Bolsonaro government for helping to put it in office. This time, too, the unthinkable Jair Bolsonaro will have government machinery to support his reelection, and a continued strategy of denial and deflection that has proven successful for those long three-and-a-half years. This time, there will be protests; the streets will be full again. This time, the chances of violence are significant, for the wounds of 2013, 2016, and 2018 are still bleeding and Brazil is as polarized as the United States, if not more so.

A Fruitful Collaboration Focused on Urban Policy in Brazil

If the past decade feels like half a century, it is also because we have been busy working. The research agreement signed in 2013 between UT and the São Paulo state research foundation, FAPESP, brought architecture and urbanism professor Ana Paula Koury to the Forty Acres in 2015 and 2016. The project on which we collaborated looked into conceptually reconciling the scholarly literatures on state planning and community participation, using the periphery of São Paulo as a case study. In October 2015, students from the UT Austin School of Architecture spent a week in São Paulo; later that year, students from São Judas University came to UT. Two seminars were organized the following year, one here and one in São Paulo. The discussions we had in those two intense years of research collaboration became a book proposal. Written between 2016 and 2019, Street Matters: A Critical History of Urban Policy in Brazil was published in May 2022 by the University of Pittsburgh Press.

The book explores the idea that we can interpret Brazilian inequality through the lens of the relationship between street protests and urban policy, making explicit the conflict between popular democracy and economic interests in the production of the space on the periphery of Western capitalism. Having space as the main variable of analysis allows us to discuss the production of the Brazilian city as both an instrument and the consequence of an unequal society. The tension of street protests is the foundation on which conflicts of Brazilian democracy have been based. By analyzing the historical changes brought about at such moments, we can derive important lessons for urban policy in Brazil. The narrative seeks to uncover different historical moments and evaluate the political agenda of the Brazilian state versus its popular movements, demonstrating that the struggles for the construction of a more just society are inscribed in the spatial arrangements of the main Brazilian cities, for better and for worse.

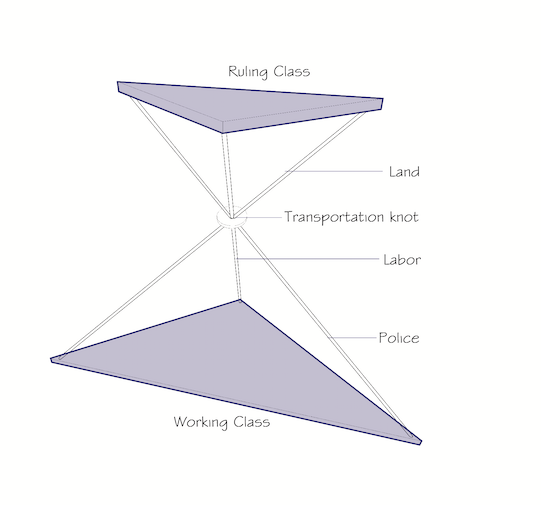

To try to understand the relationship between space, social movements, and the extreme inequality of Brazilian society, Koury and I introduce a conceptual diagram to theorize those relationships. Following Manuel Castells’s suggestion that “we need a theoretical perspective flexible enough to account for the production and performance of urban functions and forms in a variety of contexts” (1983: 336), we propose a theoretical tripod formed by the columns (rods) of work, land, and security, and joined by the transportation knot. The rods form two pyramids—one at the base, symbolizing the working classes holding up the system, and one at the top, inverted, representing the elites.

Another inspiration for our theoretical tripod comes from Arturo Escobar. His Encountering Development (1995) is the key to our diagram. Escobar was the first to demonstrate that there is no modernization without colonization. The very process of modernizing implies the colonial practice of imposing values and beliefs of ruling elites onto large swaths of the population.

Our tripod diagram encompasses the modernization/colonization mirror in its very structure. Every action taken by the ruling elites from the top down in the name of modernization has an effect on the working classes below. The opposite is also true: social movements’ political pressure and protests (their more radical form) push for changes in societal structure that impact the stability of those at the top of the social strata.

The tripod structure guarantees comfort for those who live at the top (good jobs, land tenure, and a protective police force) while submitting the majority at the bottom to precariousness at work, informality in housing, and police repression. Regressive policies enacted by the ruling elite have the effect of augmenting the distance between those above and those below. Progressive change pushed by social movements has the effect of shortening the distance between the classes, making life less privileged for the ones above. Protests, both by the working class and by the affluent classes, take place when the rods expand (more inequality) or contract (less inequality). If the rods grow, it means that life becomes more unbearable for those below. If the rods shorten, this threatens the privileges of those above.

Starting from this diagram, and stitching together 120 years of intense correlation between urban policies and social movements, Street Matters seeks to contribute to the reassessment of the meaning of popular participation in the Brazilian historical process, considering the strategic defense of the democratic state and its redistributive role through urban public policies. For instance, we discuss the fact that Emperor Pedro II (r. April 1831–November 1889) signed a budgetary supplement to finance a land survey in October of 1889 and suffered a military soft-coup a few weeks later. Was that a coincidence, or an early reminder that land conflicts are at the root of Brazilian problems? Less than two decades later, in 1906, the city of Rio de Janeiro exploded in a revolt that was blamed on mandatory vaccination (interesting how little we have evolved in 116 years), but how much of that instability was created by the demolition—without compensation—of thousands of housing units in the central areas of Rio since 1903?

We also discuss at length how Getúlio Vargas (president 1930–45, 1951–54) understood the relationship between housing and labor policy, anchoring his sectorial institutes of retirement and pension on much-needed real-estate investment. That anchor generated thousands of housing units made available to an educated middle class that had unionized jobs, but did almost nothing for the majority of uneducated Brazilians who labored in informal arrangements. After the Vargas strategy proved insufficient in the 1950s, Jânio Quadros (president January–August 1961) was the first politician to understand the demands of residents of substandard housing at the periphery, moving from the São Paulo city council to the presidency in fifteen years. In our tripod diagram, Vargas pushed part of the middle class to the upper pyramid of privilege, keeping all rural workers and most of the urban periphery on the bottom. Quadros, for his part, promised benefits for the urban periphery but could not deliver, resigning after he realized that the tripod structure of inequality (which he called “occult forces”) was stronger than his presidential powers.

More recently, the military government investment in metropolitan planning collapsed once the slow process of redemocratization shifted power back to municipal governments. With mayors competing for federal money and Congress happy to intermediate the delivery, the idea of central regional planning was never able to bypass the funding mechanism. The Estatuto das Cidades, signed into law thirteen years after the 1988 Constitution, cemented this decentralization in the hopes that cities would have autonomy to take care of their own spaces. The reality is that the budget to build infrastructure and to implement housing policy had always been concentrated in the hands of the federal government, with members of Congress as intermediaries. This state of affairs, as inefficient and personalized as it had been, yielded results for the working class. Most areas on the peripheries of Brazilian cities improved their infrastructure in recent decades, with electricity and clean water leading the way and sewage connections lagging behind. The dissemination of participatory processes in the 1990s also strengthened the political clout of the working class, with very good results.

Interestingly enough, none of those improvements changed, or even threatened, the inequality structure theorized in our tripod. Water and electricity, along with more educational opportunities and a public health system (Sistema Único de Saúde, SUS), improved people’s lives but kept constant the distance between the rich and the poor. The election of Lula da Silva in 2003 looked like more of the same at first, but it did enact change in the theoretical tripod by raising the minimum wage above inflation and promoting economic expansion (via consumption), shortening the labor rod as a result. It bears remembering that police repression did not change during the Lula years, nor was there enough of an effort to give land rights to the inhabitants of the periphery. Much to the contrary, the poor improved their lives during the Lula years by consuming more, a move that made the rich even richer.

When the growth by internal consumption model started to sputter during the first term of Dilma Rousseff (2011–2014), both the elites and the working class took to the streets to protest in June of 2013. The poor saw their lives worsened by longer commutes (the transportation knot) and decaying infrastructure, and they shouted that they wanted schools and hospitals raised to the standards of the Padrão FIFA, the luxurious specifications imposed by the international football association for the stadiums and hotels built for the 2014 World Cup.

The elites were also protesting that they could not get by as comfortably as before. After Rousseff was reelected in 2014, a more conservative Congress led by runner-up candidate Aécio Neves and House Speaker Eduardo Cunha created all kinds of legislative problems to derail Rousseff’s response to the economic crisis. At that point, in 2015, the streets filled with protesters again, but now there was nobody clamoring for better hospitals and better schools. Alongside the crowds protesting corruption, cleverly presented by the mainstream media as a problem solely on the left, there were people calling for the return of the military dictatorship in order to “get their country back.”

Implications for the Future

Looking at 2022 through the lenses of our theoretical tripod, we clearly see the rods working to maintain the distance between the rich and the poor. The police are happy to take selfies with wealthy protestors on one side of the street and brutalize low-income youth on the opposite sidewalk. The labor gains of the Lula years were dismantled fast, and young people from the periphery who were the first in their families to go to college found only menial jobs.

And what about the land rod, one might ask. This has been the slowest to change since João III of Portugal (r. 1521–57) created the Hereditary Captaincies in 1534. In summary, the improvements of the Lula years (mostly labor gains) evaporated quickly, and the problems, such as police repression and land concentration, remained unchanged. Worse yet, the long and slow political process required to rebuild Brazilian institutions dilapidated by the 2016 coup and the Bolsonaro years seems to be poisoned beyond repair. Isolated and lagging in the polls, Bolsonaro is radicalizing his discourse and normalizing talk of another coup if the election does not go his way. Lula, on the other hand, is trying to create a broad alliance, inviting right-of-center politician Geraldo Alckmin to run as vice president on his ticket, all but guaranteeing that he will not tackle inequality and push for labor gains as he did twenty years ago.

The Brazilian streets will once again hold the keys to the future, either full of protesters or emptied by the military/police apparatus. My guess is that we will see both, and it will not be pretty. ✹

Fernando Luiz Lara is R.G. Roessner Centennial Professor of Architecture at The University of Texas at Austin. Most recently, he is author, with Ana Paula Koury, of Street Matters: A Critical History of Urban Policy in Brazil (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2022).

References

Castells, Manuel. 1983. The City and the Grassroots: A Cross-Cultural Theory of Urban Social Movements. University of California Press.

Escobar, Arturo. 1995. Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Princeton University Press.