BY SUSANNA SHARPE

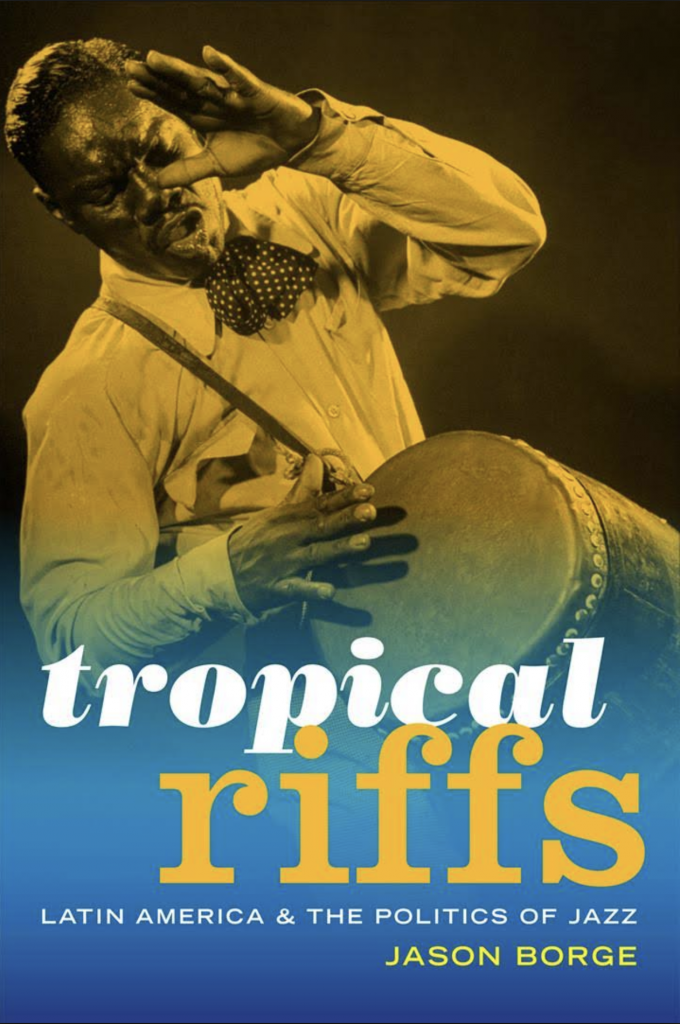

In his new book, Tropical Riffs: Latin America and the Politics of Jazz (Duke, 2018), Jason Borge uses jazz as a way to interrogate the complex intersections of North and South, race and class, cultural identity, and even politics and foreign policy.

The very earliest seeds for its writing, says Borge, were planted in 2001, when, toward the end of his years as a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, he watched Ken Burns’s groundbreaking ten-part PBS documentary, Jazz. Borge describes his reaction as “both enraptured and horrified.”

In the introduction to Tropical Riffs, Borge discusses Burns’s egregious omission of the contribution of Latin American and US Latino musicians to the development of jazz. He is far from alone in his inquietude. The documentary was called out by critics for being “stubbornly Americanist,” veering toward “cultural xenophobia,” and erasing Latino musicians from jazz history.

It would be quite a number of years later that Borge would set about writing his book. In the interim, however, he came to realize that “the story that mattered most to me was not what Latin America meant to the US jazz establishment so much as what jazz meant to Latin America, particularly during the music’s heyday between the 1920s and the 1960s. I knew that it was a book that still had not been written, and I felt that it needed to be.”

In researching his book, Borge, an associate professor, explored what jazz signifies in Latin America, focusing in particular on Argentina, Brazil, and Cuba. This exploration reflects his broader interest in cultural studies, cinema, politics, and literature. Similarly, the courses he has taught in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese since arriving at UT Austin in 2009 bring together representations of race, class, national identity, music, dance, and more; they include seminars on cinema, cultural politics, popular music, and critical hemispheric studies at the graduate level, and Brazilian/Latin American film and culture, literature, and music in cinema for upper-division undergraduates. He teaches in Spanish, English, and Portuguese.

An interest in the transnational dimensions of film and music is a thread that runs through Borge’s scholarly work. His first book is titled Latin American Writers and the Rise of Hollywood Cinema (2008). Cinema features prominently in the early depictions of jazz in Latin America, says Borge. In fact, early Latin American awareness of jazz was about image almost as much as sound. “The first arrival of jazz is not only musical,” he explains, but also depended greatly on journalism and film. In early 1920s Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro, for example, Hollywood silent films of the Jazz Age often had live accompaniment, and local newspapers were full of reporting on and images of jazz.

Beyond the exploration of jazz as music, and how Latin American and Afro-Caribbean musics and musicians would make their indelible mark on the genre in different ways, Borge writes about jazz as a stand-in for complex relationships having to do with race, class, sexuality, nationality, and cultural hegemony. In the introduction to Tropical Riffs, he writes, “[I]n the early to mid-twentieth century, . . . popular and elite Latin American audiences alike understood jazz as the product, however strange, of conditions fundamentally analogous to their own disjunctive social environments, a range of cultural expressions seemingly both modern and primal, timely and syncopated.”

It’s all pretty tantalizing, and a Tropical Riffs companion YouTube playlist is available at this Duke University Press link.

For academics, there is always a next project. Borge is currently researching the life and career of Booker T. Pittman, a US-born clarinetist and saxophonist who was the grandson of Booker T. Washington and the son of musician and teacher Portia Pittman. After performing with various US-based orchestras of the 1920s and early 1930s, Pittman moved to France and eventually South America, where he would remain for the rest of his life. There, he became “a touchstone for ‘authentic jazz’” in both Brazil and Argentina, says Borge. In addition to influencing many of the Latin American jazz musicians with whom he played, Pittman was musical mentor to his Brazilian stepdaughter, the singer Eliana Pittman.

Like Tropical Riffs, Borge’s research on Pittman can be understood within the context of his interest in “hemispheric circuits of popular culture, pan-Americanism and expatriotism,” and how US popular or mass culture has been consumed or digested in Latin America to be reborn as something new. In both of these projects, Borge continues to explore a paradox: how the “uniquely multipurpose, shape-shifting, mobile character of jazz” is both a quality attributed to its singular Americanness and at the same time, that which makes it “a transnational project and a collective idea.”

Susanna Sharpe is communications coordinator at LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collection and the editor of Portal magazine.