BY ARIEL DULITZKY

DURING THE LAST ARGENTINE DICTATORSHIP, at a ceremony marking the 123rd anniversary of the Rosario Police Department in the Province of Santa Fe, Argentina, then Chief Augustín Feced stated that a “political subversive” could never be from Argentina—adding that “[he] should not even be considered our brother . . . this conflict between us cannot be likened to that between Cain and Abel.”1 As is well documented, the main repressive tool used by the Argentine dictatorship was the systematic practice of enforced disappearances.2 Can we liken the biblical story of Cain and Abel to the practice of enforced disappearances and the response of the international community to that practice?

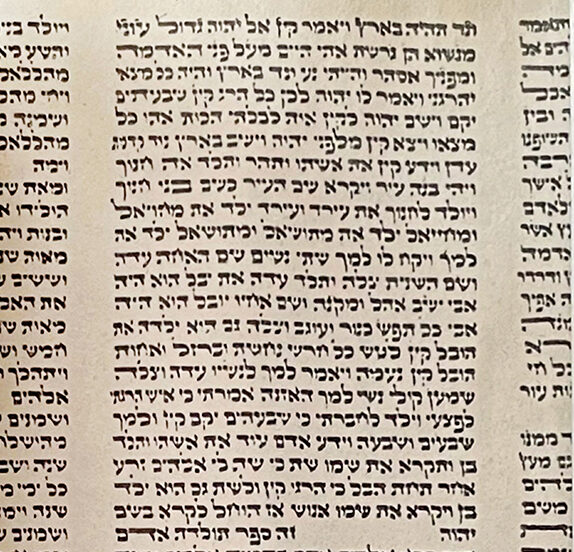

Let us start by recalling the story of Cain and Abel (Genesis 4), the two sons of Adam and Eve—Abel “a shepherd of flocks” and Cain “a tiller of soil.”

Now it came to pass at the end of days, that Cain brought of the fruit of the soil an offering to God. And Abel he too brought of the firstborn of his flocks and of their fattest, and God turned to Abel and to his offering. But to Cain and to his offering God did not turn, and it annoyed Cain exceedingly, and his countenance fell. And God said to Cain, “Why are you annoyed, and why has your countenance fallen? Is it not so that if you improve, it will be forgiven you? If you do not improve, however, at the entrance, sin is lying, and to you is its longing, but you can rule over it.” And Cain spoke to Abel his brother, and it came to pass when they were in the field, that Cain rose up against Abel his brother and slew him. And God said to Cain, “Where is Abel your brother?” And he said, “I do not know. Am I my brother’s keeper?” And God said, “What have you done? Hark! The voice of your brother’s blood is shouting out to me from the ground. And now, you are cursed even more than the ground, which opened its mouth to take your brother’s blood from your hand.” (Genesis 4:3–11)

In the story of Cain and Abel, we have the same basic contours of a disappearance and the struggle to find the proper response to it. Cain felt resentment and anger toward his brother Abel. In the case of enforced disappearances in Argentina, repressors considered the victims as their enemy and as less than human.3 In response to his grievances, Cain decided to take Abel to a secret place, the fields. In Argentina, the security forces kidnapped some 30,000 persons and took them to hundreds of secret detention places throughout the country.4 After killing Abel, Cain does not respond to the question of his brother’s whereabouts. Similarly, in the Argentinean case, the perpetrators have denied any knowledge of the detentions and denied having any information on the fate or whereabouts of the thousands of disappeared persons. (Denial of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person is a constitutive element of the crime of enforced disappearance.5)

From there on, we have struggled with the same questions: Where is your brother? אי הבל אחיך Where are the disappeared? ¿Dónde están? And we keep receiving the same response “I do not know.” The families of the disappeared do not know what happened to their loved ones.6

“Where are you?”: Biblical Questions and the Disappeared

Commentary by Rashi, the medieval French rabbi, connects the Cain and Abel story with the previous chapter of Genesis, when God asks Adam “Where are you?” (איכה Ayeka). Rashi explains in both instances that God knew the answer. Rashi says, however, that God wanted to give Adam and Cain the opportunity to repent and assume responsibility prior to the imposition of proper punishment. Rashi explains that God is asking “Where are you in this moment, what are you doing, and where are you going in this life?” (Rashi’s commentary on Genesis 3:9). Adam and Cain argue that they were afraid, or that they did not know the answer (Genesis 3:10 and 4:9).

The question of Ayeka is asked several times in the Hebrew Bible. In contrast, Rashi explores one response—Hineni (הנני “Here I am”)—as the “reply of the pious . . . an expression of humility and an expression of readiness.” In addition to being spoken by Abraham (Genesis 22:1, 22:7), Hineni is also repeated by Jacob (Genesis 31:11 and 46:2), Joseph (Genesis 37:13), Moses at Mount Sinai (Exodus 3:4), by Isaiah (Isaiah 6:8), and by God (Isaiah 58:9). Rashi writes that Hineni is “a language of humility and alacrity, immediately responsive” to a command (Genesis 37:13). In all these instances, Hineni is a full personal and spiritual response, expressing a readiness to assume responsibility and to act upon that responsibility.

Hineni speaks to a way of seeing ourselves vis-à-vis others and the world at large. In the words of Rabbi Shmuly Yankowitz, “The fundamental commitment of being a Jew is to answer the question, ‘Ayeka’ (where are you?), with ‘Hineni’ (here I am), affirming a sense of responsibility and obligation to the other.”7

“The Invisible Presence of Thousands”

In Argentina and in many other parts of the world, family members of the disappeared deal with the same question of Ayeka and struggle with the same Hineni. While the Torah’s Ayeka and Hineni are personal questions and responses, the powerful message that they transmit allows us to extend their force to society in general and to the international community. Where do we stand? What is/was the right way to behave to confront disappearances? Am I / are you/they/we going in the right direction? Have we acted correctly? How can we correct and overcome the failings and shortcomings?

The international human rights community could be questioned as well as to whether it has answered the plight of the disappeared with a clear Hineni. In one of the first international meetings on enforced disappearances, the Argentine writer Julio Cortázar made the same connection between Ayeka and Hineni:

In this hour of study and reflection, destined to create more effective instruments in defense of freedoms and rights trampled by dictatorships, the invisible presence of thousands and thousands of disappeared precedes and exceeds and continues all the intellectual work that we can carry out in these days. Here, in this room where they are not, where they are evoked as a reason for work, here we must feel them present and close, sitting among us, looking at us, talking to us. The very fact that among the participants and the public there are so many relatives and friends of the disappeared makes even more perceptible that innumerable crowd gathered in silent testimony, in implacable accusation.8

From Cain and Abel, back to Argentina.

Alicia Irene “Moni” Naymark, 31, was kidnapped on November 10, 1977, in Buenos Aires by a group of armed men who identified themselves as members of state security forces. Since then, her mother, my mother (Moni’s cousin), myself, and many more have been asking, “Where are you, Moni?” “Where are the other 30,000 who were disappeared by the Argentine state?”

I have spent the last 25 years of my life trying to find adequate answers to the question of where are the disappeared: What is the proper remedy for enforced disappearance? What is the proper punishment for those who perpetrated the crime? What are the rights of the relatives of those who disappeared? I have studied, and try to influence, how the international community has responded to the Ayeka. Have the international human rights systems effectively said Hineni?

I remain committed to providing a personal, familial, legal response to Ayeka and to understanding (and, hopefully, influencing) the meaning of an effective Hineni. As with Abel in the Bible, the voices of the disappeared continue to cry out. Hineni is our response to Abel. Hineni is the response to those voices, too.

Ariel Dulitzky is a clinical professor of law and director of the Human Rights Clinic at the School of Law, University of Texas at Austin. Between 2010 and 2017 he was one of five independent experts in the United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances and served as its chair-rapporteur in 2013–15. A native of Argentina, Dulitzky has dedicated his scholarly research and his legal career to human rights—particularly the issue of enforced disappearances. The Jewish idea of Tikkun Olam (repair the world) influences his identity and his work.

Notes

1. Cited in Marguerite Feitlowitz, A Lexicon of Terror: Argentina and the Legacies of Torture (New York: Oxford, 1998), 27.

2. See Nunca Más: The Report of the Argentine National Commission on the Disappeared, with an introduction by Ronald Dworkin (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, in association with Index on Censorship, 1986).

3. Ibid.

4. Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Report on the Situation of Human Rights in Argentina (1980).

5. International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, Article 2: “For the purposes of this Convention, ‘enforced disappearance’ is considered to be the arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation of liberty by agents of the State or by persons or groups of persons acting with the authorization, support or acquiescence of the State, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person, which place such a person outside the protection of the law.”

6. The Bible appears to suggest that Adam and Eve knew what happened to Abel. “And Adam knew his wife again, and she bore a son, and she named him Seth, for God has given me other seed, instead of Abel, for Cain slew him” (Genesis 4:25).

7. Rabbi Lauren Grabelle Herramn, “From Ayeka to Hineni: Showing Up & Taking Responsibility in a Broken World,” available at rabbilauren.medium.com/from-ayeka-to-hineni-showing-up-in-a-broken-world-273c239e3db7.

8. Julio Cortázar, “Negación del Olvido,” address given at Coloquio de París, February 1, 1981, available at cels.org.ar/common/documentos/cortazar_negacion_olvido.pdf (translation by the author).