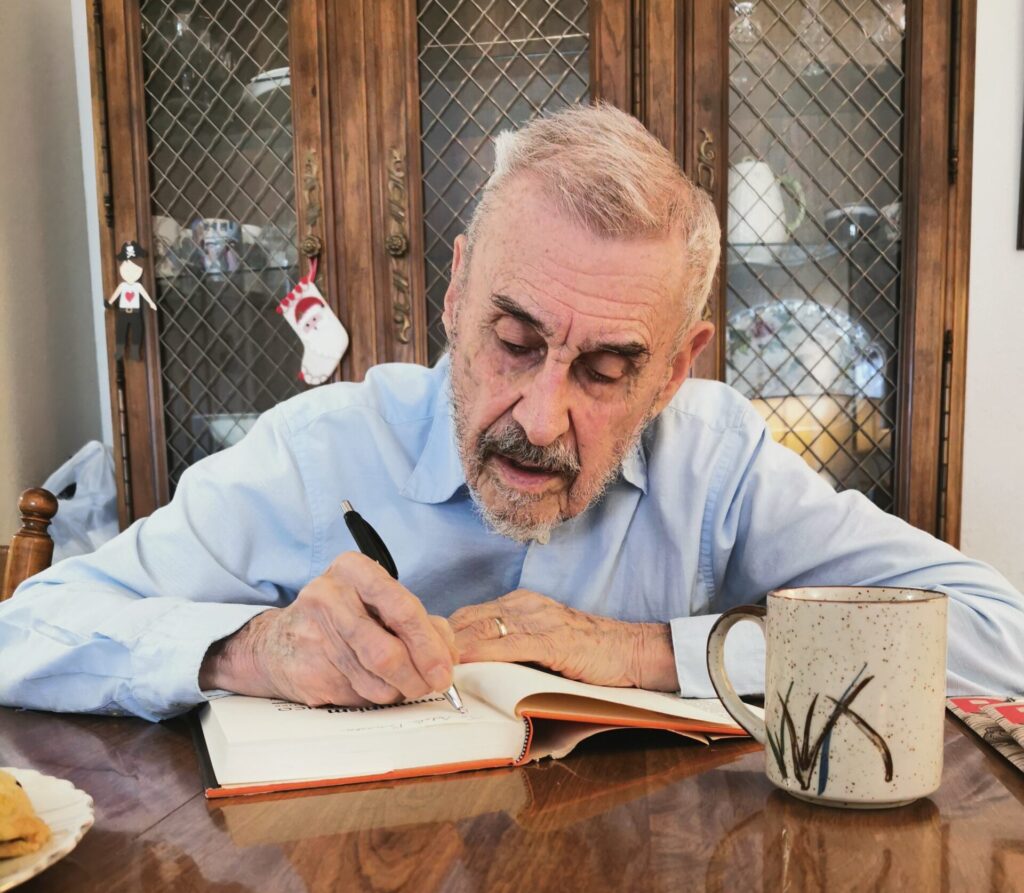

PROFESSOR EMERITUS KARL MICHAEL SCHMITT joined the faculty of the Department of Government at The University of Texas at Austin in 1958, where he spent the majority of his career as a prominent Latin Americanist. He became associate director of the Institute of Latin American Studies (ILAS, now LLILAS) in 1968, under director Stanley Ross. He has been an advocate of LLILAS ever since, particularly through his support for the Hackett Lecture series. I visited Karl at his home in Austin to talk about his career as a historian and political scientist, his love for libraries, and his long-standing relationship with LLILAS. Brilliant yet unassuming, Karl has an infectious vitality, enjoys good company, and is a natural conversationalist. A centenarian this year—his 100th birthday is July 22—his unique perspective allows us to conceive of the institution of Latin American Studies at UT as an important archive of U.S.–Latin American relations during the Cold War and beyond.

Karl’s reflections on his life and career are now collected in a memoir, which he recently donated to the Benson Latin American Collection. During our visit, we discussed the field of Latin American Studies during his lifetime. His anti-doctrinaire spirit and utter rejection of pomposity and self-congratulatory approaches to Latin America make for refreshing conversation.

Adela Pineda Franco

Lozano Long Professor of Literary and Cultural Studies

Director, Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies

Could you talk about your academic trajectory? What motivated you to become a Latin Americanist?

It was purely an accident. I enrolled as a freshman in 1940 at the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC. I received a work scholarship that paid for my tuition. In my freshman year, I was assigned to the library. It was there that I met Dr. Manoel da Silveira Cardozo, who, at the time, was an assistant professor of history and the curator of the library. The library was quite disorganized, so he made me move books from one place to the other. In the process, I became interested in Latin America. I did not know about the region, yet the more I read, the more I wanted to learn. Catholic University was small, basically a graduate school. Once I got into my junior year, I realized that there were no more undergraduate courses to take, so I could only major in American or European history. Latin American history was not an option. So, I majored in American history and my second field became Latin America. At the graduate level one could specialize in Latin America, and that is what I did when I began my MA at the same institution.

My mentor, Cardozo, who belonged to the Azorean/Portuguese community, was a Brazilianist, a pioneer in the study of Luso-Brazilian history in the United States. Yet Mexico became my main area of research because I was attracted to the study of its revolution. Also, one of my closest friends was from Mexico, Alberto Casares. When I met him in 1940 and during my years at the Catholic University, Alberto remained very anti-revolution. His family had lost their lands. As years went by, Alberto came to admit that the revolution was a necessary change.

I find it very interesting that your initial connection to Latin America was a library.

The Oliveira Lima Library at Catholic University got me started. I used to read every book that looked interesting. Although the Latin American collection was small, it was a good collection. However, I must admit that Catholic University did not achieve what Texas did with its Latin American Collection, thanks to Nettie Lee Benson. I really began to understand the importance of libraries when I was writing my dissertation at the University of Pennsylvania.

What do you think about the role of mentors in choosing academic fields?

My main mentors were Cardozo and, at UPenn, Arthur Preston Whitaker. That was the way I was socialized into academia. I don’t think students think that way anymore. When Cardozo advised me on where to pursue my doctorate, he did it in terms of mentors, not programs. At that time, I was interested in Mexico, particularly in the Reforma period and in Church–State relations. I wrote my MA thesis on this subject.

For my PhD, I chose UPenn because I was impressed with Whitaker. He was the one who admitted me, not the department. I really liked what Whitaker was doing. I read his two-volume book on the Mississippi question. I admired his intellectual qualities, his fondness for clarity and precision, and how well he wrote. As a mentor, Whitaker was enormously supportive, but I did not like his personality. Once he threw me out of his office. I called Cardozo and said, “I am coming back, Manoel, I can’t stand Whitaker.” Cardozo obviously replied with an assertive “No, Karl, you are not coming back.”

When and why did you come to UT Austin?

My first job was teaching at a small college in upstate New York, Niagara University. It would have been a dead end if it had not been for Whitaker, who recommended me for a job at the State Department. That was a fascinating position, a five-year appointment as an intelligence officer. Then came the offer from UT Austin. A number of people, including historians and colleagues in the State Department, warned me about coming to Texas. There was political interference in academic life, they said. But I did not listen. I was attracted to the position because of the library, and I knew it was heavy on Mexico because of the Genaro García Collection. This was around 1957 or 1958. I wanted to join the History Department because I was a historian, but the invitation came from Malcolm Macdonald, who was the chair of the Department of Government. The real challenge for me was that I had to change disciplines and had to immerse myself in the new theories of human behavior and statistics, which, at the time, were shaping the discipline of political science. I did it, but not with the necessary depth of knowledge it required. I think I had a good career, but not a great career.

Can you talk about the reach and scope of your scholarly work?

A central theme of my scholarship on Mexico was the study of Church and State relations. My first publication was about the complex role the clergy played in the independence of Mexico. My main argument was that, although there was no consensus over Mexico’s independence among the creoles and mestizos forming the lower clergy, this group was the only one with strong ties to the masses; thus, an important sector of the lower clergy supported the initial rebellion, joining the insurrection and monopolizing the field of rebel journalism. In contrast, it was only after the Riego revolt in Cadiz that the upper clergy, fearful of the Enlightenment, supported the independence of Mexico, which was controlled by conservative forces by then, against a liberal-governed Spain.

I have also written about the Reforma (1857–1861) and the Porfiriato (1876–1911). My original plan was to write a complete history of Church–State relations. I envisioned several volumes, from the independence movement to the present, highlighting continuities and breaks of that relationship beyond the conventional periodization of Mexican history.1 Coming here prevented me from fulfilling this plan because I had to write about politics. So, I began to write about the politics of violence, in particular. I studied the politics of assassination, highlighting cases such as Trujillo and Somoza.2

The book that got me tenure was Evolution or Chaos: Dynamics of Latin American Government and Politics (1963),3 a study of Latin America in the context of Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress.

Communism in Mexico (1965) got me my professorship. The initial investigation that went into this book was the result of research I carried out in the State Department. It analyzes Mexican communism through its political organizations and fronts in the context of Mexico’s PRI-driven political system.

What was your connection to the Institute of Latin American Studies at UT?

Macdonald mentioned the institute when he offered me the position at UT. When I arrived at UT, the institute was rather small, largely a degree-granting operation. Yet, it began to change in the early 1960s. In 1962, John Parker Harrison became the new director. Richard Adams was his associate director. This was the Alliance for Progress period, so, the U.S. government began to provide many funding opportunities for Latin American Studies projects. Harrison and Adams knew how to obtain grant funding and they began to sponsor substantial research and publication. Many professors in all sorts of disciplines became affiliated with the institute, even physical education professors were conducting comparative-oriented projects. In 1967, Harrison was finalizing his tenure as ILAS director. He called me and said he had funds that needed to be spent before the end of the academic year and offered support for my research. Hence, the institute granted me four thousand dollars to research and study congressional campaigning in the Mexican state of Yucatan. I interviewed all the candidates, except the PRI, who did not grant me an interview. Of course, the outcome of the elections was clear even before it started. PRI was going to win.4

When Jack Harrison left, the university hired Stanley Ross. He was also a historian, and he had published a fine biography of Francisco I. Madero. It was then that I was asked to become the associate director of ILAS. Since Harrison, each successive director has left an imprint on the institute. I am certain that the institute will keep expanding and diversifying its operations in years to come. ✹

Notes

1. Some of Schmitt’s salient publications in this field are: “The Clergy and the Independence of New Spain,” Hispanic American Historical Review 34.3 (1954): 289–312; “Catholic Adjustment to the Secular State: The Case of Mexico, 1867–1911,” The Catholic Historical Review 48.2 (1962): 182–204; “The Mexican Positivists and the Church-State Question, 1876–1911,” Journal of Church and State, 8.2 (1966): 200–213; Church and State in Mexico: A Corporatist Relationship, 1984, available at jstor.org/stable/981118; The Roman Catholic Church in Modern Latin America (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972).

2. Schmitt’s main contributions to this field: Carl Leiden and Karl M. Schmitt, The Politics of Violence: Revolution in the Modern World (Hoboken, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1968); Clark Havens Murray, Carl Leiden, and Karl Michael Schmitt, eds. The Politics of Assassination (Hoboken, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1970).

3. Karl M. Schmitt and David D. Burks, Evolution or Chaos: Dynamics of Latin American Government and Politics, intro. by Ronald M. Schneider (New York: Praeger, 1963).

4. Related to this research, Schmitt published Congressional Campaigning in Mexico: A View from the Provinces, 1969, available at jstor.org/stable/165405.