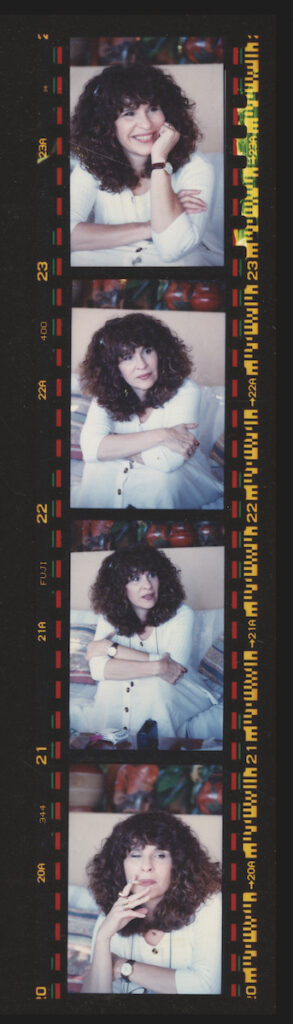

GIOCONDA BELLI, one of the foremost figures in Nicaraguan literature and politics, has chosen the Benson Collection as the home for her archive. Belli is the acclaimed author of nine novels, a memoir, two volumes of essays, nine poetry collections, and four children’s books. She has been the recipient of several major literary prizes over her decades-long career, including the prestigious Casa de las Américas Prize for poetry (1978) and the Reina Sofía Ibero-American Poetry Prize (2023). Known for her feminist writing and erotic poetry, Belli has a broad international following, with works translated into at least 20 languages. The English translation of her memoir, The Country under My Skin, was a finalist for a Los Angeles Times Book Prize.

As is true for many Nicaraguan writers, Belli’s life has been deeply intertwined with the political history of her country. She was among the leaders of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) that defeated the Somoza regime in 1979, and worked in support of the Sandinista government until separating from the FSLN in 1993. As the Daniel Ortega–Rosario Murillo government resorted to violence and political persecution to cling to power, Belli grew increasingly vocal in her opposition to the regime. As a result, in February 2023, Belli, along with 93 of her fellow Nicaraguans, was stripped of her citizenship and declared a traitor to her country. She now finds herself living in exile for the second time.

In celebration of the acquisition of Belli’s archive, I am pleased to share this interview, in which she responds to my questions on a range of topics. Her answers appear in translation here. Click to read the original Spanish.

As a longtime admirer of her literary work and her activism, I am honored that Gioconda has entrusted the Benson with her collection. We look forward to engaging students and faculty with the archive, and to welcoming Nicaragua’s greatest living poet to Austin in the near future.

Melissa Guy

Director, Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection

You are among Nicaragua’s greatest writers, and you also have a broad international readership. In your opinion, what is it about your work that resonates across so many audiences?

When I began to write, in the seventies, my poetry was considered revolutionary for the way in which it dealt with the female body. I think that writing about sexuality, motherhood, and my own process of liberation from concepts that subordinate women gave my words a power that many women recognized as their own. That power transcended nationalities, because we all share those types of experiences and we also needed to change the discourse on women as sexual “objects,” to one of woman as the owner of her body and “subject” of her own sexuality.

The other aspect of my poetry and novels that captured the attention of readers and critics was their social context. Due to my own experiences, I wrote about women who participate in armed struggle against a dictatorship, a role very different from the traditional one, and also full of contradictions regarding the passive identity that was acceptable for women.

I think also that being a poet helped me develop a different narrative. I was very interested in portraying the world in my novels through a woman’s gaze, which included sensitivity and emotion without succumbing to the sentimentality associated with what was known as “feminine” literature. The thing that most surprises me when I say this is that despite all the time passed and the progress for women, women’s eroticism and the problematics of the female body are still as relevant today as they were in the seventies. The same can be said of themes related to politics and societal relationships. My novel La mujer habitata [The Inhabited Woman], published in 1988, continues to be among my most popular books.

What literary work are you most proud of, and why?

I feel proud of my poetry when I see how it resonates with readers. Two of my novels were fundamental for my development as a writer. One is La mujer habitada, for the impact it continues to have, and the other is El infinito en la palma de la mano [Infinity in the Palm of Her Hand], because it is the novel where I succeeded in combining narrative with poetry, and using the biblical Eve to challenge the concept of woman as Adam’s “seductress” who is at fault for the loss of Earthly Paradise. To defy the biblical Genesis was a wonderful creative challenge.

You are living in exile, yet again, from your beloved Nicaragua. What it is you most want readers to know about the current situation in your home country?

It is heartbreaking that a revolution that cost so much effort and so many Nicaraguan lives has regressed to once again become a dictatorship similar to the one that was overthrown in 1979. Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo have perverted the positive values of the revolution and exacerbated its most negative aspects: authoritarianism and restrictions on freedom and democracy. Their discourse has polarized the country; it justified the massacre during the popular protest of 2018 by using the past of the eighties, inventing a supposed coup d’etat plotted and financed by the United States, and accusing all who question [Ortega-Murillo’s] power of being allied with “North American imperialism.”

In the first few months of 2023, over 300 Nicaraguans were illegally stripped of our citizenship, and 94 of us were stripped of our assets—our homes and even our retirement pensions were confiscated. Opposition to the government has become a crime punishable by imprisonment, exile, and removal. More than 500,000 Nicaraguans have emigrated in the last five years. Poverty continues to be endemic, and the country is more isolated each day, subjected to a news blackout, a constant state of terror, and a state of legal limbo. There is no rule of law beyond the whims of the government. It is a tough tragedy for a country that has suffered so much.

Regarding your novel El infinito en la palma de la mano, a reimagining of the story of Adam and Eve, you write, “In my novel, Eve does not lose Paradise but decides consciously that life on Earth, with its pain and its joy, is preferable to a perfect life and immortality.” How does this philosophical scenario—this conscious choice—relate to your own life, both in general and on the subject of your forced exile from Nicaragua?

I am not religious, and I believe that to tolerate injustice and relinquish one’s own fate to the idea of a “divine” will causes human beings to lose the ability to make decisions and lose the courage to take the reins of our own lives. To be active and responsible for one’s reality, to be a protagonist in one’s own story, has its risks, but I think it is the most consistent way we have of practicing humanism and growing as conscious beings.

Why did you choose to deposit your archive in the Benson Latin American Collection at The University of Texas?

I knew that the Benson has the most complete and rich collection related to Latin America. If the conditions had existed for my archive to remain in my country, I would have made that choice. But the political instability in Nicaragua made it uncertain that my archive would be conserved properly. In contrast, at the Benson, I know that my papers will be well organized, well cared for, and above all, freely accessible to whomever wishes to consult them. I also wanted to add to this important collection the work of a Latin American woman writer who, I believe, made a difference in women’s writing in the region.

What sorts of materials will students and researchers find in your archive, and what clues will they give to your life as a writer, your creative process, and perhaps nonliterary aspects of your life as well?

Through interviews, notes, newspaper clippings, letters, and original manuscripts, the materials in my archive show both the development of my political and philosophical ideas and the development of my career as a writer. There is a lot of interesting material—photographs, articles, family papers, correspondence with writers like Harold Pinter, José Coronel Urtecho, Salman Rushdie. Ultimately, I believe the material will be very valuable from a sociological as well as a literary point of view.

What advice would you give to aspiring women writers, or aspiring writers in marginalized groups?

That they not view marginality as an insurmountable disadvantage, that they concentrate on the quality of their work, that they study, read, and be confident that with effort, tenacity, and constancy, it will be possible to leave their own imprint and contribute to knowledge and to the development of the ideas of humanity as a whole. No one is marginal if what they live and bear witness to is part of the human condition. ✹

Translated from the Spanish by Susanna Sharpe.