BY RACHEL E. WINSTON

The vision for the Black Diaspora Archive at The University of Texas at Austin came into focus in 2013 as a collaborative project between Black Studies, LLILAS Benson, and the University of Texas Libraries. After years of continued successful collaboration, Black Studies approached LLILAS Benson with the idea of creating an archive devoted to the Black Diaspora. Since its founding in 1921, the Benson Latin American Collection has actively collected Latin American materials that document communities and people of color, but it had never done so in a planned and dedicated way. Very quickly, leadership in each unit recognized the common objectives and shared vision between them, and the mutual benefit of a dedicated archival holding of material related to the Black Diaspora. With additional support from the Libraries and the Office of the President, the Black Diaspora Archive came into being, and in the fall of 2015 I joined LLILAS Benson as its inaugural Black Diaspora archivist.

This position is a special one—not only is it one of its kind, but the element of collaboration that grounds the project and guides both the quotidian and visionary work that I do to support it strays from the job description of a typical archivist. Though it may be untraditional, it suits me, and I am excited about the ways in which my professional efforts complement one another and work toward the benefit of preserving the legacy of Black people in both a local and international context.

The Black Diaspora Archive

The Black Diaspora Archive’s mission is to collect documentary, audiovisual, digital, and artistic works related to the Black Diaspora—that is, people and communities with a shared ancestral connection to Africa. While the geographic collecting area for the Black Diaspora is global, at present this collection is focused on materials documenting experiences from within the Americas and the Caribbean. In addition to collecting, this initiative aims to promote collection use and research through scholarly resources, exhibitions, community outreach, student programs, and public engagement.

While the archive continues to grow, it remains important for me to actively bring in materials that express and represent the Black experience from the Black perspective—meaning individuals who are considered to be Black, identify as Black, or are perceived as Black. Such individuals can include scholars, professionals, and activists/activist movements, for example. Thematically, the collection seeks to reflect art and art scholarship of the Diaspora, slavery in the Americas, ethnoracial empowerment and advocacy, and the personal archives of scholars and thought leaders. These types of records can include historical works, prints, digital and born-digital content, and other rare material.

As the primary manager of the Black Diaspora Archive, my ultimate charge is to provide a fuller understanding of the Black experience throughout the Americas and Caribbean with primary sources. In the most traditional sense, this necessitates the acquisition, collection, preservation, and accessibility of archival records. However, as our communities become more connected and technologically advanced, information access and information needs continue to evolve in ways that are increasingly less traditional. User needs of today, for example, live largely in the digital realm. In facilitating access to online content, the archivist has more of a responsibility to perform outreach and promote information literacy skills in an effort to preserve the integrity of our collections and meet user needs. To be relevant and effective in responding to changing demands, it is my responsibility to remain flexible in considering how archival records and collections can be of greatest contribution value.

The burgeoning digital humanities landscape also presents exciting opportunities to engage and build the Black Diaspora Archive. Through the use of digital humanities—computational software that analyze and interrogate data, texts, and themes—we can create new interpretive readings of history generally, and the materials in Black Diaspora Archive more specifically. I am genuinely enthused by the ability to incorporate digital scholarship into the Black Diaspora Archive in its early stages, including initiatives like the Texas Domestic Slave Trade project, and I look forward to discovering new ways of integrating physical collections with digital tools and scholarship.

Texas Domestic Slave Trade Project

In the spring of 2015, while I was a graduate student at The University of Texas School of Information, Dr. Daina Ramey Berry and I came together to assess the locally available eighteenth- and nineteenth-century archival collections relating to the slave trade in Texas and borderlands with Mexico. Through this work, the Texas Domestic Slave Trade (TXDST) project was born. Our initial research unmasked the lack of scholarship on the domestic slave trade and experiences of the enslaved in the region: it made clear the pressing need to better document and understand this historical period and to bring this content into the public and digital humanities space. Now, as manager of the Black Diaspora Archive, I am able to continue this work through the archive’s collaborative partnership with TXDST.

TXDST research has proven Texas to be a central point in border crossing and slave trading. Texas gained statehood in 1845, almost twenty years before the Civil War, and settlers from across the United States and Mexico flocked to the region to exploit lenient land acquisition policies and a terrain that was prime for cultivating sugar and cotton. These early settlers brought human chattel along with them during the years prior to 1845, when the Spanish and Mexican governments occupied the territory, as well as after Texas achieved statehood. The enslaved laborers brought to the region were often stolen, kidnapped, or purchased from other points around the country. Even though it served as the western edge of the domestic trade in the United States, Texas is often overlooked as a major hub of trade in favor of neighboring Louisiana and New Orleans—a city that notoriously served as the slave trading epicenter of the Deep South. Texas, however, was active in slave trading, which included the illegal trade of enslaved people directly with Mexico, and as far south as Central America.

To best showcase and engage the rich content from this project, it is critical that TXDST research and resources be openly accessible for scholars, researchers, historians, and students. For that reason, TXDST will continue to develop as a digital scholarship project. It is important for us to illustrate this history through images of primary documents, landscape photographs, maps, and other digital content to provide the contextual information from which we encourage expanded scholarship to take place.

Project Team

In establishing this project, Dr. Berry and I, along with our expanded and interdisciplinary research team, now have a platform to better illustrate the legacy and impact of the domestic slave trade and its influence on the state of Texas. Our team brings together undergraduate and graduate students, faculty, and staff from across campus. Their individual areas of expertise in U.S. slavery, border crossing, gender, race relations, oral history, geography and mapping, public history, and the curation of historical content collectively lend valuable perspectives to the project.

Accomplishments

Within the past couple of years TXDST has made continuous, significant progress. During the 2015–2016 academic year, the project received a Media Project Grant, funded by the Humanities Media Project in the UT College of Liberal Arts. This grant was established to promote the use of media in humanities research, with the intention to expand beyond traditional academic audiences. Specifically, the grant funded our project “Mapping the Texas Domestic Slave Trade Routes,” which enabled us to create a digital history of the Matagorda region of Texas.

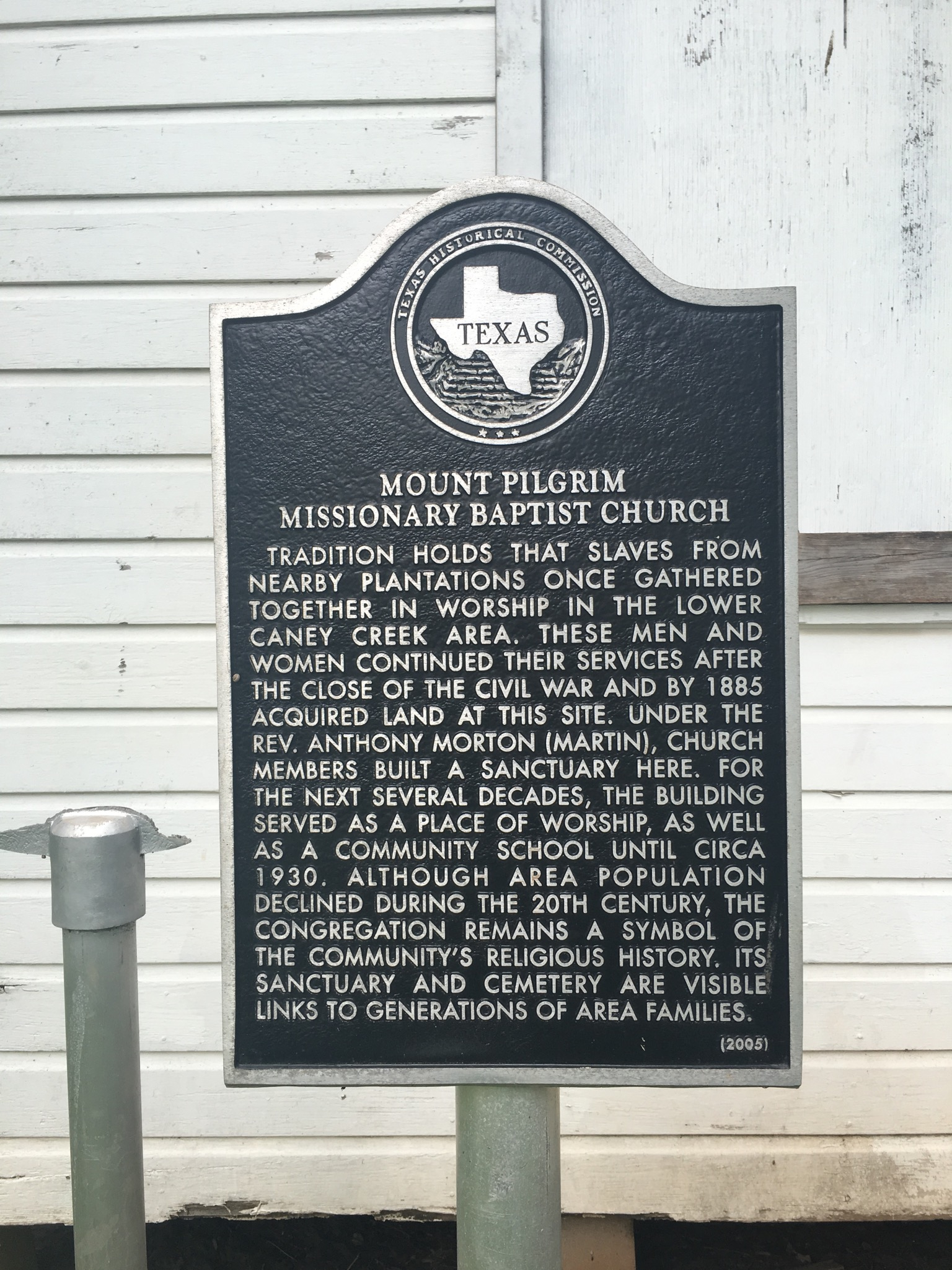

Located in southeast Texas, just south of Galveston and at the confluence of the Colorado River and the Gulf of Mexico, Matagorda was an active point of commerce throughout early Texas history. However, the city’s role as an entry point for enslaved people and its impact on the domestic and transnational slave trade have yet to be explored. The goal of this project was thus to document, through photos and digital media, the landscape and history of the region. Grant funds allowed for our team to visit Matagorda and surrounding counties to capture this information through research and primary document analysis at sites throughout the area. The grant also allowed for the creation of a website from which to showcase this project, which can be viewed at txdst.la.utexas.edu.

Looking to the future, TXDST is positioned to make significant contributions to the research and study of Texas and its role in the domestic slave trade. It is my hope that as the project advances, not only will the research community benefit, but the students and project team members who work with us will, too.

***

Leading the university’s effort to build the Black Diaspora Archive is a real privilege. The collaborative nature of the project has led me to discover many of the outstanding resources on this campus, and has also helped to build a network of faculty and staff who are interested and invested in the success of the archive. I am particularly grateful for the opportunity to do this work out of LLILAS Benson, where there is institutional concern for post-custodial archival practice, ethical collecting, and social justice.

Rachel E. Winston is the Black Diaspora Archivist at LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collection, The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin). She holds a degree in anthropology with a minor in French from Davidson College, and is an alumna of the Coro Fellows in Public Affairs. Winston received her MSIS with a graduate portfolio in museum studies from UT Austin in 2015.