- Spivak pisses me off.

- the idea by Gramsci that the traditional intelligentsia commits all sorts of ideological errors and has myopic vision while the organic intellectual had direst access to a firm and discrete class perspective.

- traditional intellectuals exist over time, less connected to immediate politics

-

“worker or proletarian, for example, is not specifically characterized by his manual or instrumental work, but by performing this work in specific conditions and in specific social relations”

- all men are intellectuals, but not all men have the function in society as intellectuals, the distinction is for the social function of a professional category.

- Keynesian as the end of the traditional intellectual?

-

“The mode of being of the new intellectual can no longerconsist in eloquence, which is an exterior and momentary mover of feelings and passions, but in active participation in practical life, as constructor, organizer, “permanent persuader” and not just a simple orator”

- “The relationship between the intellectuals and the world of production is not as direct as it is with the fundamental social groups but is, in varying degrees,”mediated” by the whole fabric of society and by the complex of superstructures,of which the intellectuals are, precisely, the “functionaries.””

- “There is no human activity from which every form of intellectual participation can be excluded”

- fight over political ideology is conducted through an invisible fight over language ideology, with Turkish’s open war on vocab choice, and Arabic’s denial that there is any language problem at all. The problem gets summarized as though it’s state vs. openness (the Bakhtian contra Stalinism) and anxiety about state reforms in Turkey and Fusha in Arabic, rather than seeing how easily language registers move and shift, how little actual speech is disciplined by the type of state language policy that we typically think of as language ideology. The idea that language is taught in ideological state apparatuses and in Anderson’s print media, that an author’s fight for freedom and creativity is only against the state. Rather, everyone is constantly performing and enacting language ideology, a general cognitive-domain-general habit of thought, working through the indexical order in rural peasants as much as in language academies. Keynsianism was both the high water mark of state legitimacy, but also the period of its undoing in terms of linguistic dominance.

- I want to pull these writers and their use of language away from an ideological clash with the state, and towards language practice in society, to see how they’re engaged just like anyone else in the practices of language ideology, which simultaneously exposes their distortions, but also enjoins them to rather than puts them above, society.

-

Language ideology is:

-

creating a social field and making judgements about it based on they way people speak and use language. The judgement is about language itself, as a reified object, so not just Bourdieu. They do it using Irvine and Gal.

- thinking of language as langue and not parole, as a state project which regulates and determines everything, rather than a diverse “organic ideology”

- imagining either that there is a stark distinction between dialects and registers rather than seeing it as a continuum. Imagining sharp epistemological breaks that come from national language projects. Overplaying peasant ignorance which is in fact just a different register.

- imagining a site from which language practices emanate, that intellectuals produce slogans and language patterns (Silverstein and Bybee show us how we don’t need them for the model)

-

-

We stigmatize the way that leftist writers and intellectuals are stuck on one side of the divide from the “people”. That their efforts to speak for or represent the subaltern, or the working class, are hopelessly myopic. That subaltern consciousness is irretrievable or unknowable. That intellectuals and the state are the only ones parroting slogans. That those slogans, when repeated by the subaltern, are foreign and imported. But how much of this anxiety can actually be explained by language ideology? That is to say, to what extent are we projecting that divide based on the language divide we tell ourselves exists because of language ideology.

- The subaltern doesn’t speak in a radically different way, sticking to MSA or using Ozturkce doesn’t get any farther away.

- How much of the practices of the peasants described by Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoğlu are portrayed using language difference? How much of his project was plagues by language anxiety. Louis Awad writes his all dialect Plutoland as a bold statement, but then writes a novel where dialect and MSA are all mixed in together.

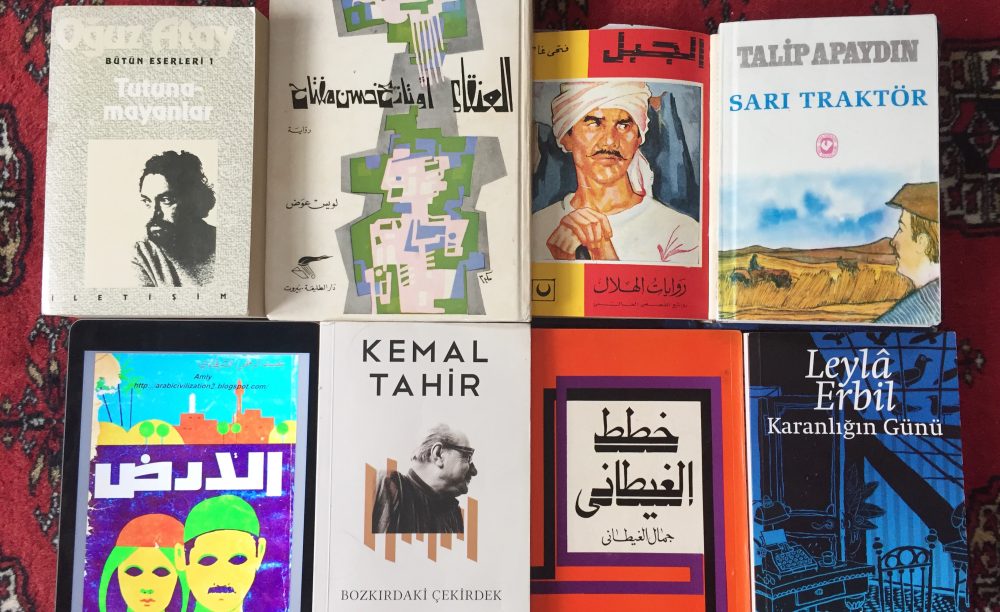

- Doesn’t Bozkirdaki Cekirdek show us that the subaltern have their own agendas, and freely mix and match state discourses with their own priorities and power arrangements? Can’t we see how little bearing state language has on their speech, and yet how fully articulate it is, not at all restricted or unexpressive.

- In the three Egyptian Kurosawa novels, what exactly do we think keeps us from seeing Zohra’s perspective, we see her speak don’t we?, when we finally get access to Yusif in man who lost his shadow, don’t we see him parroting the state?, the soldiar in war in the land of Egypt is actually dead, nothing to access. What I’m saying is imagining something irretrievable about silent or minor characters is to assume their language has a s radical alterity and is not socially constructed (reifies the speaking subject rather than their already social constructed consciousness)

- There is no national language, no andersonian creation other than which is confirmed by media, and leftist writers wring their hands about it when they try to portray non-intellectuals, as though there is a chasm between their language and that of the people. They reify language difference through fractal recursivity and because of this create the gulf and feelings of guilt.

- On the “other side” the exact same language practices and ideologies are going on, there is no hidden essence, just different language practices. In bozkirdaki Cekirdek the smugglers have their complete own language and discourse, mixed with elements of state propaganda and organic ideology, but it’s their autuonomous discourse, which itself makes exactly the same sorts of assumptions and stereotypes. Yasar Kemal would be a bad example of this for fetishizing peasnt consciousness as radically different.

- The peasant in Sharqawi’s fallah is a whole jumble of propaganda and folk beliefs. They are not on the other side of a linguistic gulf, they are also mixing and matching beliefs, engaging with the indexical field not as passive subjects but as creative agents in the promulgation of ideology.

- shukri’s al-rihla as somehow “authentic” or on the otherside of the divide, how does it think about language difference?

Part II

- Turkey and Egypt have neurotic relationships with their national languages. Engineered official registers which apparently distance or cut off or reign in heteroglossia. The demands of Pan-Arabism, secularism, and modernity. This is even before considering minority languages. Just talking about the national language itself.

- National language policy is treated as a boogeyman which retarded the “true” or “authentic” expression of vernacular speech. It is seen as “an untranscendable horizon governing thought –its forms, contents, modalities, and presuppositions so deeply and insidiously layered and patterned that they cannot be circumvented, only deconstructed.” (The Postcolonial Unconscious, Lazarus) This has much to do with seeing radical alterity in language practice. “People in the countryside add the ‘b’ prefix to their present tense verbs, or drop the r in present tense Turkish verbs, how could they possibly understand the stakes of national liberation.

- But state intervention plays a fall smaller role in lived language practice, and even in the “ideological” transformations of language, than it is popularly understood. We can show using Silverstein how ideology can be propagated without a center. We can use Charles Ferguson to problematize the illusion of diglossia. Irvine and Gal to show how normative judgements overlay conceptualizations of linguistic difference. Sociolects and dialects are not state planned.

- The period of Keynsianism when the state was supreme, when these battles were supposedly decided, show constant anxiety towards drawing out distinctions and difference as well as the growing efforts to celebrate the subaltern and advocate against their silencing.

- But the divide between Fusha and dialect, and between Kemalist linguistic reforms, paint a picture of a great linguistic divide, but this more a projection of linguistic ideologies (particularly Fractal Recursivity). The differences perpetuate themselves. language difference is read as ignorance and gullibility. The obsession with language difference is not merely that of state agents and elites, but is internalized by even those on the left opposed to it, who want to elevate “subaltern speech” or have a special concern with reaching “the people”.

- It’s not promoting vernacular forms of speech as much as it is reifying the distinctions, attempting to get at some authentic form of speech, some radically different consciousness, in these cases, is more trying to get to the other side of a linguistic border within one’s own language which is created through Fractal Recursivity.

- Neil Lazarus on the subaltern “But I wonder whether the narrative, formal, and affective dimensions of The Hungry Tide do not cut against and in the end undermine this idea of incommensurability, and of the theoretical anti-humanism that underlies it. Ghosh’s self-conscious use here, as elsewhere in his work, of sentimentality and sensationalism (the novel’s very title is significant in this respect), of romance and narrative suspense, all point us in a quite different direction, towards the idea not of ‘fundamental alienness’ but of deep-seated affinity and community, across and athwart the social division of labour.”

- Progressive novels from this period in both countries, concerned as they are with both attempting to accurately portray the masses, and expressing their remorse at not being able to do so, frame the question as reaching the people. This neurotic “two-faced populism” (hamlet Kuşağı pg. 60) is in many ways an effect of language ideology.

- It is as though the more you attempt to imitate authentic speech, or to respect the relativity and radical difference of their consciousness, the farther they recede.

- Novels are a great record of this, because

- a) they are cultural/ideological products constructed using language

- b) they are supposed to be linguistic/ideological interventions, but at their best are merely reflective of complex linguistic realities.

- c) the use of dialogue vs narrative can be focused on as a way to underscore the fetishization of linguistic difference. (It’s not that differences don’t exist, it’s that they’re not a big deal). The dichotomies of fact/fiction and objective/subjective mirrors the dichotomy between official vs. vernacular speech.

- these case studies show how

- a) authors make a huge deal about diglossia, but don’t even follow their own rules, authenticity falls for the “direct discourse fallacy” = relationship between language ideology and narratology. authentic portrayals are not inaccessible beyond a linguistic/consciousness wall because that wall is largely imagined.

- b) ideologies circulate through language via the indexical order, not unidirectionally from intellectual and authoritative centers, illiterate villagers are just as capable of creating and promoting ideologies through their daily use of language as intellectuals. “There is no human activity from which every form of intellectual participation can be excluded” – Gramsci. The idea that intellectuals and writers are particularly guilty of ideological projections is bullshit.

- c) the common theme of intellectual isolation from the people, while true politically for other very valid reasons, is framed a problem of language, as “finding the right words.” As though some magic combination would unlock their remote secrets. petty-bourgeois anxiety is turned inward, as a forensic investigation of their own language.

- Chapter one: the subaltern is doing their own thang regardless of intellectuals and state language policy. Bozkirdaki Cekirdek and al-Fallah: Get all into Gramsci on immminent language and indexical order.

- Chapter two: Bir Gun tek basina and august star: the workers on the other side of a fake wall, the illusion of radical incommesurability

- Chapter three: al-rihla, unmediated access to the real deal, vs. the kirosawa novels as all circling the character: not some consciousness or language separate from social discourse.

- Chapter four: Orhan Kemal vs. Yaşar Kemal: language fiction and dialogue: what’s “real”