Normative Grammar, Language Ideology and the Political Novel in Turkey and Egypt

- What is the effect of metalinguistic awareness and language ideology on the political novel? How do authors work as one point in networks of beliefs

- From a linguistic standpoint, what are the actual differences between normative and imminent grammar? What makes it different isn’t something qualitative within its structure itself, but in the way it’s imagined and treated by speakers. Not only is dialect not a deficient form of normative language, but the two really aren’t that different from one another.

- How does a novel have to grapple with language ideology in a way that film or radio do not? How does a novel create metalinguistic awareness? How does dialogue work as a vehicle for representing speech? How is it used as a barrier between normative and imminent grammar?

- How have authors been judged according to their fidelity to vernacular speech? What is the discourse surrounding this? How is vernacular speech marked and made different? What is the history of iconizing vernacular speech as ignorant, and the subsequent shift to valorize (fetishize) it instead.

- How did authors understand and project anxiety about diglossia and normative grammar? What were the conversations about language in literary circles?

- How role does fractal discursivity play in creating and sustaining the anxiety of vertretung in writing? How is difference dramatized through attention to dialect? How are social distinctions imagined for dialect difference? Does imagined difference create its own barrier?

- Why is normative grammar seen as the vehicle for ideology while imminent grammar is not? How do the politics of the novel move around questions of language ideology?

- What is the relationship between language ideology and mimesis in the novel, how is fact and fiction judged according to the perceived value and communicability of forms of language? How does the novel form complicate notions of accuracy, authenticity, and representation?

Intervention: using field of language ideology to reframe the history of the T/E political novel, seeing how much questions of representation and form are a reflection of anxiety over the perceived divide between normative and imminent grammar.

Chapters:

- The history of language ideology in modern Egyptian and Turkish literature – intervention against the state language ideology narrative, also against literary histories which use oversimplified history of language

- language reforms and the post-war period

- the myth of diglossia and normative grammar

- literature and its linguistic ideological baggage

- Fiction, Vetretung, and language ideology – an sociolinguistic intervention into the vertretung debate. You have to look at how language itself works as a form of representation. village novel histories have noted it without analyzing it and the paradox it creates.

- the direct discourse fallacy and the stakes of mimesis

- novels as opposed to film and radio

- The receding subaltern as a function of fractal discursivity

- why metalinguistic awareness is a trap

- various strategies for representing popular speech and their reception

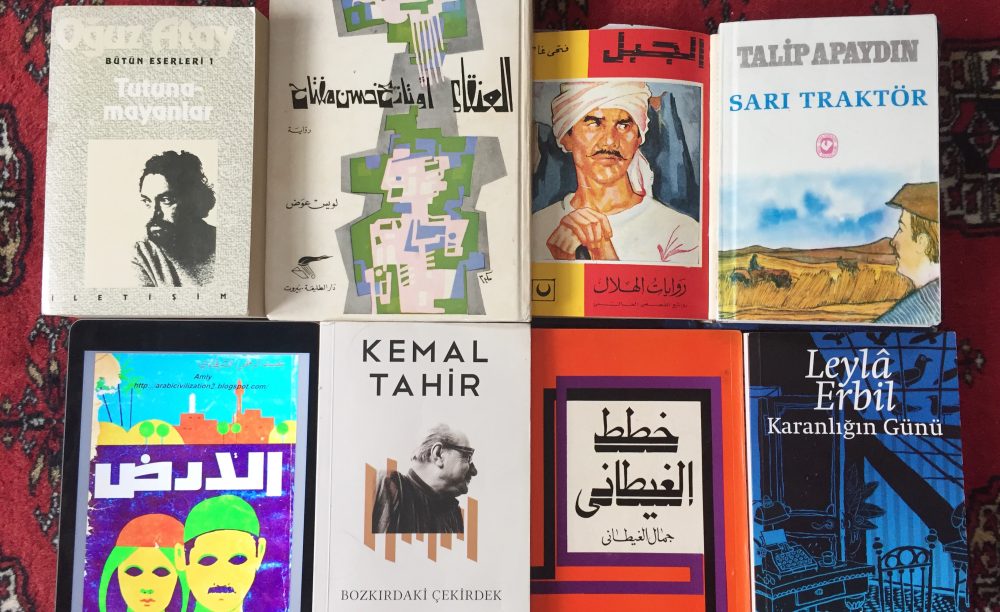

- the Kemal’s – earnestness, mythology, irony

- something from Egypt

- The Left and its failure to communicate – an intervention on how ideology travels in language, the relationship between linguistic and political ideology

- leftist parties and their efforts to reach the masses

- The Roman a These and normative grammar

- the ikidegerlilik of populism, petit bourgeois anxiety as a focus on the failures of normative grammar to communicate

- ideology is only something that normative grammar does.

- Phoenix and one day all alone

- Lost in normative grammar – intervention showing relationship between language politics and literary formalism

- Looking at language used in novels as a material/historical object, historicizing a retroactive fiction.

- reacting to state censorship, cultural policy and lexical politicization (left/right)

- postmodernity as a deep dive into the artificiality and performance of the language

- searching for the real in artificial language, getting nowhere: khitat and tutunamayanlar

- 1980s shift in language hegemony and rise of the marketplace of imminent grammars.

Interventions:

Chapter one intervenes in the narrative of the pervasiveness and effectiveness of state language policy in Turkey and Egypt, as well as the historical rhetoric surrounding the ‘problem’ of diglossia. It also challenges the emphasis on the state and institutions in perpetuating language ideologies, showing how important micro-contextual interactions are to the movement of normative perceptions of language difference and just how autonomous imminent language actually is.

Chapter two a sociolinguistic intervention into the vertretung/dartellung subaltern debate. I will argue that writers like Samah Selim in The Novel and the Rural Imaginary in Egypt have worked from a concept of textuality that does not adequately account for the material sociolinguistic dynamic at work in the village novel. Unlike other studies of the village novel in Egypt and Turkey, I will maintain my focus on the language ideology of writers themselves and show how various textual attempts to capture authentic speech are premised on an illusory distinction between fictional and spontaneous language.

Chapter three is an intervention on the relationship between political ideology and language ideology, and the ways in which they interact dialectically. It looks in the rhetoric of the left for evidence of the language-ideological belief that normative grammar is capable of self-aware political thought whereas imminent grammars are reflexive and passive. It also gives a sociolinguistic account of how slogans and other forms of political language actually travel in speech, and the ways that left-wing novels have misunderstood this.

Chapter Four is an intervention into work like “the Wounded Tongue” by Jale Parla which have conflated the interplay of language politics between the state and canonical literature with the Turkish and Arabic language as a whole. The rhetoric of normative grammar, and the literary rebellions against it, both take place within the sphere of elite language practice, dramatizing the impact that either the state or literature has over the development of imminent grammars which continue to hum along. Their impact, rather, is restricted to a normative grammar which is always, by its very nature, the product of coercion and political interventions.