the novel as a product of language ideology, it condensed into a cultural object. Works have not considered the mechanics of how the novel works to confirm and promote linguistic imaginings of society.

rather than focusing on novelistic representations of “the people” and seeing how well they square up, this is a look at how authors imagine themselves cut-off or remote from them based on language ideology. The idea of radical incommensurability or inability to communicate or connect with the people arising from fractal recursivity. That the language was too official or ornate. Changes in literary stye and anxiety about its artificiality. Understanding petit-bourgeois anxiety as based in language ideology. The failure of populism based on the imagination of authors.

to what extent is “the people” or rural groups actually a mirage of fractal recursivity. But this isn’t a work about depictions of the countryside or workers and their accuracy, but the imagined linguistic barriers that authors themselves put up and imagined.

introduction – history of language reforms vis-a-vis the novel and literature. linguistic baggage, how literatis imagined their languages as elite and artificial from 1920-1950s, but how metalinguistic awareness of it often only made things worse. Salama Musa, Karaosmanoglu. Village novel as conflating linguistic difference with social difference. More about fantasies of diglossia than what the actual social field was like. the supremacy of language ideology in the 1950-80s, normative vs. imminent grammar.

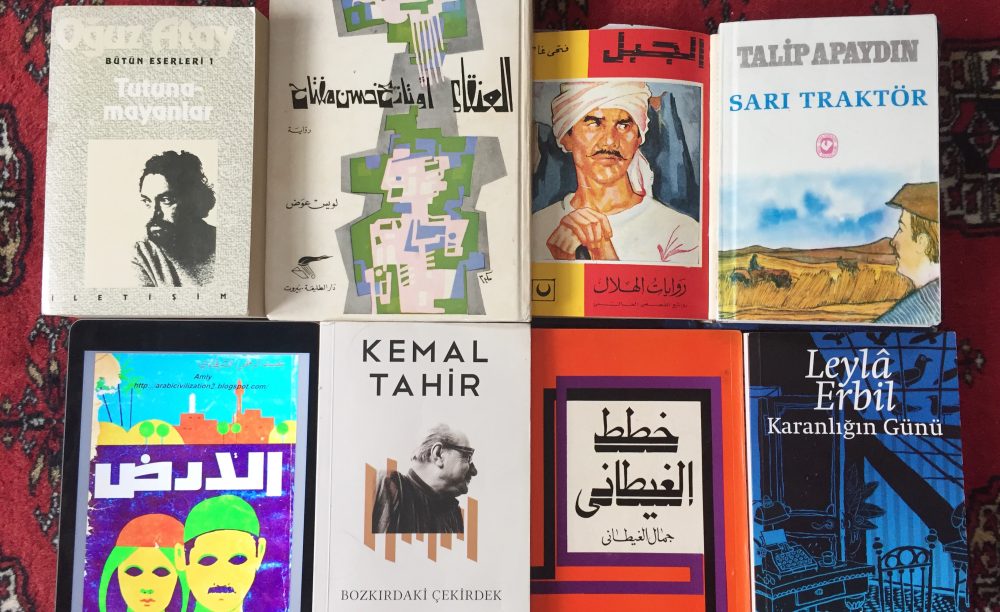

fiction, dialogue, and the social real – what is actually representable in fiction, how being attendant to diglossia and the efforts to get at the real end up strengthening difference. mimesis and dialogue. direct discourse fallacy. relationship between narratology and sociolinguistics. the ideological linguistic inevitability of the novel form. yashar kemal – vs – Orhan kemal – vs – al-rihla (all are performative)

the failure of rhetoric and politics – phoenix and, one day all alone. seeing political marginalization as the inability to communicate, the relationship between party politics, slogans, political language, and the failure of leftist parties to articulate a legible discourse.

the search for understanding in performative language – khitat al-ghitani and Tutunamayanlar and deep dive into the artificiality and performance of the language, allegorical attempts to come to answers about the social field. looking for answers in normative grammar.

sarcasm, mocking the idealism – awbash and bozkirdaki cekirdek and indexical order. building “deep-seated affinity and community, across and athwart the social division of labour.” through a tone of sarcasm and acknowledgement of the universal ideological use of language.

- focus on nationalism and populism and left politics through the lens of language ideology

- focus on the state and its language policy has a huge influence on metalinguistic awareness in literature

- in Egypt its the fusha/ammiya divide and the anxiety over authenticity, the idea that you aren’t accurately representing “the people,” this anxiety is only in literature since film and radio don’t have this metalinguistic awareness in the same way, but because of the prestige of the written language, people are tied up in knots.

- In Turkey it’s the Kemalist reforms and the language as “engineered” or “artificial” or “restrictive.” A divide between the engineered language and the countryside or the uneducated. Often a sense of self-culpability, metalinguistic awareness of the constructedness of elite language, contrived when the language of “the people” is natural

- Both cases are overstated. Normal imminent language in many ways carried on.

- also the assumption that somehow ideology (meta-awareness of ideas as ideological resulting from matalinguistic awareness) is tied to intellectual forms of language, that their ideas and theories are somehow elevated beyond common sense, qualitatively different from popular beliefs

- But in reality, the linguistic divides is more a product of the language-ideology imagination than it is an empirical fact. It is a function of fractal recursivity. It exists in literature and progressive populist ideas rather than in the social field. Actual people use language and develop and espouse beliefs in the same way. The particulars of the language may just be different.

- In what ways did language ideology play into the neurotic “ikidegerlilik” of populism and in what ways do novel archive this metalinguistic awareness in a self-defeating way.

- 1) Fractal Recursivity- as a fetishization of difference. portraying popular speech as marked, either positively or negatively, or as beyond commensurability. This is equally true of rural/urban divide as it is for “workers” or “the people” or other popular social groups. The exact same ideas refracted back in a marked dialect make them appear naive, or righteous, or simply unreachable. Will be countered by Ferguson et al.

- 2) Normative Grammar- In the assumption that normative grammar is the only vehicle for ideology and that consciousness and ideology cannot be comprehended by those outside of the intellectual class, that they are beyond deciphering, that popular subjectivity is a black box, that the subaltern cannot speak. An overestimation in normative rather than imminant grammar and therefore a belief that ideology can only be projected down and out. That only intellectuals have conscious ideological beliefs and that popular classes only have passive “common sense” Will be countered by Indexical order to show how ideology works the same way for both.

- 3) Direct Discourse Fallacy – the idea that there is one kind of language that is performative and fictional, and another that is authentic and spontaneous.

- Language ideology creates artificial divides between popular and intellectual speech style, sees itself as performative or inauthentic as opposed to natural speech, and a divide between ideology and common sense. All three things cut off the “popular classes” from the forms of expression and representation available to the novel. But this divide is a figment of the imagination.

- introduction to theory, history of language policy, literary populism, literature as the site par excellence of language ideology.

- the

- the writer trapped in language

- The popular classes think for themselves – Fallah & bokkirdaki cekirdek