Jason Syvixay | Sean Bohle

Abstract

The City of Edmonton’s Missing Middle Infill Design Competition sparked significant local, national, and international interest in the possibilities for the missing middle or medium-density housing design innovation. In their proposals for five parcels of land within a core Edmonton neighborhood, multidisciplinary teams consisting of architects, builders, and developers considered impacts to residents and the surrounding community, the competition’s design objectives, and financial viability. With the incentive for participation being the opportunity to build their winning design, teams prepared pro formas to articulate how they would proceed with their developments. This study seeks to explore the assumptions that applicant teams made when designing their missing middle housing proposals. As cities continue to contemplate the necessity for missing middle in their neighborhoods, lessons gleaned from this analysis may offer potential opportunities to address financial and regulatory challenges to development; in addition to understanding the industry’s perspectives on profit and risk with respect to medium-scale housing forms. Topical policy questions for urban planners and decision-makers might be the various factors hindering development, and the policy and regulatory improvements that may address them.

Keywords

Missing Middle; Infill; Housing; Pro Formas; Design

About the Authors:

Jason Syvixay (MCIP, RPP, MCP, BSc, BA) is an urban planner currently completing his PhD in Urban and Regional Planning at the University of Alberta. He has worked as the managing director of the Downtown Winnipeg BIZ, a planner with HTFC Planning & Design, and more recently, has joined the City of Edmonton to support the implementation of its Infill Roadmap. He has a passion for people and places, and engages in city building that listens to the community, builds knowledge and capacity, and works towards equity in urban places.

Sean Bohle is an urban planner at the City of Edmonton. He discovered a love for spreadsheets and financial models while completing graduate school at the University of British Columbia, and through subsequent consulting work on affordable housing development. At the City of Edmonton, Sean has worked on policies to provide affordable housing and community amenities from rezoning, and now leads the implementation of the Infill Roadmap.

Introduction

Cities across Canada are exploring the missing middle as opportunities to welcome more homes and people in their communities. The term missing middle refers to multi-unit housing that falls between single detached homes and tall apartment buildings. It includes row housing, triplexes/fourplexes, courtyard housing, and walk-up apartments. These housing forms are considered “missing” because they have been largely absent from urban streetscapes in Canada. In 2018, the City of Edmonton shifted its focus from low-density infill to medium-density infill, creating an Infill Roadmap to steer regulations, plans, and policies towards these types of developments and investments – even hosting a Missing Middle Infill Design Competition to explore how these housing typologies could be advanced in a well-designed yet financially feasible manner.

The Infill Imperative

Over the last forty years, societal and economic challenges have driven people away from core and mature neighborhoods to settle on suburban fringes. This slow loss of people in central neighborhoods has cost Canadian cities billions in new infrastructure and servicing. However, this shift in population has also inspired many municipalities, including Edmonton, to develop strategies to curb sprawl and nurture a more compact urban form.

In 2013, the City launched a project called Evolving Infill that engaged more than 3,000 Edmontonians. From this engagement, the City created its first Infill Roadmap (2014), comprising 23 actions that comprised the City’s work plan for advancing more infill development within close proximity to quality public transit, amenities and services. This plan undertook significant regulatory and policy changes to help enable and encourage more affordable, diverse, and well-designed housing in Edmonton’s older neighborhoods.

In July 2018, the City adopted Infill Roadmap 2018, which contains a set of 25 more actions to welcome more people and new homes into Edmonton’s older neighborhoods. The Infill Roadmap 2018 takes a more strategic focus on the missing middle, multi-unit, medium-density housing such as row housing, courtyard housing, and low-rise apartments. The actions are envisioned to create new opportunities for medium-density development by managing population growth in a rational and contextual manner, responding to changing economic and cultural housing needs, reducing the city’s ecological footprint, maximizing existing and future infrastructure investments, and maintaining neighborhood vibrancy. Edmonton’s official plan, The City Plan, envisions a growth of an additional one million people, and was recently approved by council in December of 2020. Both the Infill Roadmap and The City Plan demonstrate Edmonton’s interest in increasing housing choices, particularly in the ‘missing middle’ housing range, but whether this development orientation aligns with industry and consumer demand remains a point of contention.

Murtaza Haider and Stephen Moranis (2018) question whether households prefer mid-rise housing, and if builders see these housing typologies as more profitable than single-detached or high-rise residential buildings. If consumer demand does not favour housing within the missing middle range, is it reasonable to expect that builders and developers will build it? Haider and Moranis argue that “land prices are set higher because landowners believe the builders will be able to build at a higher density than what the land is originally zoned for.” If this is true, what density is preferred for a parcel of land, and should the land value differ depending on the final densities of the project? They further argue that the “economies of scale favour high-rise construction over mid-rise construction for a given parcel because in addition to fixed land and some construction costs, some ownership costs are also independent of the number of units.” With that said, then, if cities are to focus their attention on missing middle housing, challenges around land prices and demographics may need to be addressed.

single detached homes and tall apartment buildings. Example : MIDI

According to Johnson et al. (2018), infill redevelopment is more expensive than greenfield development because of demolition costs, in addition to construction and property acquisition. How might the public sector and municipalities address these imbalances? These questions were top of mind for the City of Edmonton, and were explored as part of the Missing Middle Infill Design Competition.

Finding the Missing Middle

Launched in 2019, Edmonton’s Missing Middle Infill Design Competition encouraged conversations around infill and helped the public and development community envision design possibilities. The competition solicited and reviewed design proposals that considered how the missing middle or medium-density housing might work on a site of five lots owned by the City of Edmonton. The winning team, adjudicated by a national jury of architects, would be given the opportunity to purchase the site and build their design – with the City of Edmonton supporting throughout the development processes.

The competition sought to recognize the following:

- Contextual multi-unit, medium-density (‘missing middle’) designs for mature neighbourhoods in Edmonton

- Innovation and creativity in design

- Financial viability and buildability

- Design for livability for a range of users and abilities, including individuals, couples, single families with or without children, extended family groups and seniors

- Design for environmental, social and economic sustainability

- Climate resilient design

The five lots in Edmonton’s Spruce Avenue neighbourhood were chosen due to its sufficient size, location, proximity to transit and other services/amenities and developability – after reviewing and comparing it to thousands of City of Edmonton properties. It was deemed as surplus land by the City of Edmonton, is well-serviced, and was determined to be immediately sellable as-is by the City of Edmonton’s Real Estate Advisory Committee. While the market prospects, as predicted by the City of Edmonton, are indeed excellent (e.g. residential condo and townhome median assessed values have increased by more than 4% compared to the city-average, -2.8%), it is the existing community-at-large that have actively endorsed the Missing Middle Infill Design Competition, welcoming positive change and growth in their neighbourhood.

deliberations. Example : Bricolage

Nearly 100 renderings and 30 pro formas, representing more than half a million dollars of architectural design work, were received from Edmonton, Calgary, Winnipeg, Vancouver, and Seattle, in addition to preliminary registrations from London (UK), Regina, Hamilton, Toronto, and Oklahoma City.

Applicants to the Missing Middle Infill Design Competition were required to provide a pro forma. Creating a pro forma requires a lot of assumptions about what materials and labour will cost, how people want to live, and what they will pay for real estate.

Pro formas offer a window into the financial assumptions of developers, including relative costs of project elements (e.g. land vs. building vs. permitting). This can help policy makers understand the financial impact of various policies that change costs and project timelines. Insofar as they are accurate and represent a real commitment to a project, they can also inform policy makers of the risks developers perceive with a given project. However, pro formas are seldom used as a tool to inform or test policies. In part, this is because policy makers typically do not have the required skills to produce test pro formas, and developers typically resist sharing the detailed financial information they contain. The pro formas submitted for this project have a number of limitations, discussed later in this report, but still offer some perspective on the financial reality of infill development.

By reviewing the thirty pro formas submitted to our design competition, we sought to answer three questions as part of an analysis on the financial viability of missing middle housing. What do the pro formas from the Missing Middle Infill Design Competition tell us about the most financially-feasible low and medium infill forms? What do the estimated profit margins tell us about the risks applicants see with building infill? What funding sources and financing structures are typical for infill development and how do these differ from greenfield?

What the Numbers Say

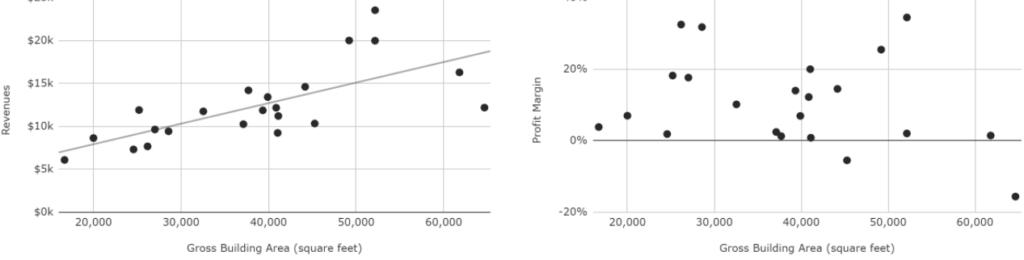

With land value held constant across all projects, the average profit margin for an apartment and row house is identical (11% of revenues). To test the impact of land value reductions, the land value was reduced by 25% for row house and stacked row house projects. Cheaper land makes row housing more profitable than apartments (15% vs 11% profit), and typically land that is zoned for smaller scale development is less expensive. Based on the data available for this study, row housing can be competitive with small apartments. The following graphs shows larger revenues for larger buildings, but a similar range of profit margins across building sizes.

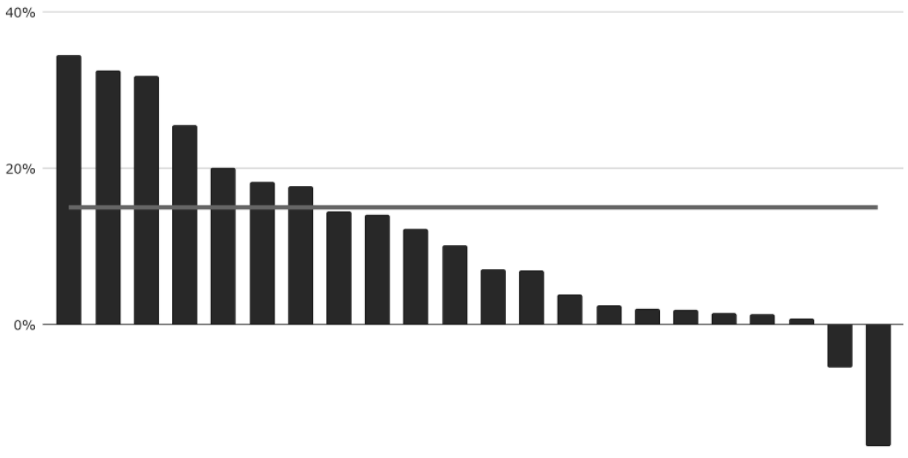

Nine of the twenty-two projects evaluated proposed rental apartments. Three of these were among the most profitable developments (ranking first, second, and ninth). The remaining six rental projects were the least profitable of all projects. The average profit margin was lower for rental projects than for condominiums (7% vs 13%). However, maximum profit margin for rental projects was comparable to the maximum for condominiums (34% vs 32%). Overall, the financial data suggest that there is not currently a clear advantage for building rental or condominium projects in this market, and that considerations other than pure financial return influence developer’s choice.

Every developer will set a minimum acceptable margin that depends on what investment options they have and the risks involved. The most common margin used by policy makers, however, is 15%. The average profit margin for this site was only 11%, meaning that for most developers, it is hard to put together a successful project.

With profit margins so low, what can we say about project risk? We might assume it means that developers think infill is a slam dunk, and so they are willing to take a small return. However, when you look closely at project inputs like rent per square foot, construction costs, and condo sales timing in a slow Edmonton market, this does not seem reasonable. In fact, we found more evidence of aggressive targets (or wishful thinking) in the pro formas than conservative estimates. For example, capitalization rates were normalized across submissions for this analysis because a number of rental projects assumed unreasonably low rates or high rents. No condominium project accounted for long sales periods that are characteristic in the current market.

over and over, and with little engagement cost or risk. High rise development is large enough to produce its own efficiencies through scale, and attract funds from pension funds. Missing middle infill development never gets the scale, the momentum, or the attention to make it an easy win.

What the Industry Says

To accompany our pro forma analysis, we invited architects, builders, and developers to share their perspectives and assumptions around profit and risk for medium-density housing, and associated financial and regulatory barriers.

Applicants to the design competition perceived their participation as a worthwhile venture and investment because of the opportunity to build their proposal. In fact, the ideas that developer-architect teams explored are, in many cases, being explored for other housing projects. The Missing Middle Infill Design Competition helped to expand our knowledge of what scale of density is preferred and reasonable for the missing middle in Edmonton. Participants noted how the design competition was an opportunity to test new design concepts, and to potentially challenge the City’s current regulations with new innovations.

“But when you’re working with the developer, you can develop a proposal on a site like that is feasible. You can push the limits of what is possible, because the architect and developer can equally push each other to make sure the proposal meets technically, economically, and also achieves the design aesthetic.” (Developer)

Our interviews also revealed that members of the industry perceive land values as a challenge to making pro formas for medium-density housing viable. Municipal government affects land value primarily through the development rights (zoning) granted to each parcel. We typically expect that adding development rights will also increase the value of land. The land in the competition was priced at for low rise apartments, but some projects proposed lower density development, like row housing. These projects could expect to acquire land with less permitted density for lower cost in an open market, as long as upzoning is not expected.

“Construction costs could not be changed. Materials cost the same, no matter what you are building. There is no flexibility, too, with architectural/design fees because of provincial recommendations. The only way to wiggle with the pro forma would have been to adjust the land cost. Infill is a niche market. Very few people can afford $800,000 duplexes.” (Developer)

Builders, architects, and developers cited how servicing requirements need to be made clear so that these costs can be appropriately factored into their pro formas. Some of these participants made assumptions that since the competition was put forward by the City of Edmonton, that there would be leniency on permitting timelines and additional incentives to support the winning team’s advancement through the land development process.

The interviews illuminated how design features like amenity space and public space are potentially at odds with density requirements for developments to be profitable. While developers strive to include public space so that their housing projects can entice their intended user demographics, their pro formas did not perform well with them included.

“We wanted more of a green wall. It just didn’t work economically. We were constantly reviewing the numbers while we were working with the design.” (Architect)

The provision of parking was also seen as a significant expense. The City of Edmonton is exploring the possibility of removing minimum parking requirements, with amendments to the Zoning Bylaw scheduled for public hearing in 2020. If these regulatory changes were factored into the design competition, would the number of parking spaces put forward by architect-developer teams be reduced, and by what measure?

Given the nature of the design competition, all projects expected rezoning fee reductions or waivers, timely permits, and a positive neighbourhood response. While municipal fees were not a major project cost, interviewees indicated that the success of their proposal depended on minimizing delays and project uncertainty. Part of what made the competition desirable was that there was an assembled site, and the City of Edmonton was taking on much of the community engagement work, reducing uncertainty and timelines for proponents.

Sharpening our Pencils

The development of new housing can be complex and costly in the best of circumstances. When it proposes a new form in an old neighbourhood, it can be very difficult to put together a project that can please neighbours, satisfy regulators, attract buyers or renters, and convince banks and investors to put their money in.

So what lessons can we draw from the City of Edmonton’s Missing Middle Infill Design Competition?

We learned that developers and architects are creative and interested in innovating when there is support from regulators, like city planners, to do so. We learned that different infill designs are possible, and even competitive — rental apartments, condominium rowhouses, even modular, stacking, expandable co-op housing can be viable on paper. If cities want row housing, they need to zone land for row housing and use those zones as a commitment to communities and developers to prevent price creep from pricing out desirable projects. Cities can use their zoning tools, along with long range planning and engagement to set community expectations and reduce uncertainty for all involved.

The pro formas tells us that most of the factors affecting real estate development are determined by the markets for labour, investment capital, and housing, which are outside of a municipality’s hands. However, interviews with developers reveal that supportive policies, regulations and proactive engagement can make the difference between a successful infill project, and a failure to launch. Cities seeking missing middle development will need to work with local developers to understand the challenges facing infill in order to find effective solutions. Cities, now more than ever, are eager to sharpen their pencils, and get moving on this type of work. We are excited for the possibilities.

References

City of Edmonton. (2018). “Planning Academy: Residential Infill 2018.”

Johnson, J., Frkonja, J., Todd, M., and Yee, D. (2018).

“Additional detail in aggregate integrated land-use models via stimulating

developer pro forma thinking.” Journal of Transport and Land Use, 11:1, pp. 405-418.

The Financial Post. (2018). “The ‘missing middle’ in real estate is missing for a reason:

No one wants to live in mid-rise housing.” Retrieved from https://business.

financialpost.com/real-estate/the-missing-middle-in-real-estate-is- missing-for-a-reason-no-one-wants-to-live-in-mid-rise-housing.

Garcia, D. (2019). “Making It Pencil: The Math Behind

Housing Development.” Terner Center for Housing Innovation. Retrieved

from: http://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/uploads/Making_It_Pencil_The_ Math_Behind_Housing_Development.pdf.