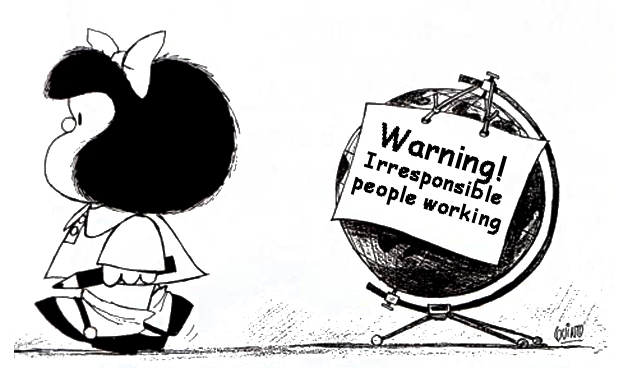

Agustín Rossi, Argentina’s Minister of Defense and potential presidential candidate, spoke at the LBJ School recently. While Rossi’s speech pointed to many of Argentina’s clear successes in terms of its relationship with South America, it was also littered with reminders of the country’s fixation with the past. This fixation is not particular to Rossi, but rather it is characteristic of the national mindset that largely dominates Argentine politics. The claims of sovereignty over the Malvinas Islands, use of outdated nationalistic rhetoric, and unwavering support for inefficient economic models are indicative of a nation that has valued nostalgia above practicality. They serve, above all else, to distract from severe inequality and nearly inexistent upward mobility.

Throughout his speech, Rossi emphasized “integration” and the “recovery of democracy” as the centers of Argentina’s defense policy. With some pride, he listed Argentina’s Defense Agencies’ accomplishments and objectives since that time. The agreements signed between South American nations, Rossi affirms, have promoted peaceful conflict resolution and cooperation in the areas of military training, production of equipment, and protocol development. In fact, since the end of the military dictatorship, Argentina has maintained consistently good relationships with neighboring countries as well as the rest of the world.

Among the issues Argentina currently faces, Rossi pointed to the militarization of the Malvinas (Falkland Islands). Great Britain has increased the number of troops and weapons on the island, meaning there are now more troops on the Falkland Islands than non-military inhabitants. According to Rossi, the British military presence is disruptive to the continent’s claim to peace, but he was quick to clarify that Argentina holds a strictly reactionary policy when it comes to military engagement. It bears noting that Rossi’s discussion of the Malvinas did not go without a statement as to the “real” sovereignty of the islands. Since the war over the Falkland Islands in 1982, Argentines claim the islands almost unanimously.

But to what end? In terms of national policy it is logical that Argentina would be concerned with the activity on nearby islands. However, continuing to claim sovereignty of the islands, when its current inhabitants have no interest in being separated from Great Britain is futile. It is important to remember that the Falklands War was launched by an Argentine military dictatorship in decline, desperate to recover some popularity and extend its rule. Keeping such a negative legacy alive seems unlikely to be beneficial by almost any measure.

Possibly in light of his future presidential candidacy, Rossi transitioned from the theme of territorial loss of sovereignty to a loss of sovereignty in the realms of financial independence and control of resources. With this transition he declared that one of the most significant threats to Argentina is not organized narco-trafficking, as many may think. Instead, he said, the greatest threats are the “vulture” funds that rob Argentina of its autonomy and financial sovereignty. Argentina defaulted on debt held by hedge funds in July. Many would agree that the “vulture” funds are just that—and true to their name, they prey on the weak in a legal, yet ethically suspect manner.

However, Argentina has held this debt for over a decade and could have begun to mitigate the situation far in advance. This lack of preventive action points to the government’s lack of long-term vision and penchant for blaming external factors for the country’s hardships. It is much easier to unite the country against the usual giants—imperialism, ruthless capitalism—under a nationalistic guise, than assume responsibility for a default. Blame of this kind is often dragged from one administration to the next so that the causes are never really understood nor remedied. History, then, continues to repeat itself.

One audience member questioned Rossi about the existence of the “Dólar Blue,” the highly devalued peso traded on the black market. The severe restrictions the government has placed on buying dollars, at a time when the Argentine peso is extremely volatile, increased the demand for a stable currency with which Argentine’s could trust their savings—the “Dólar Blue” arose from this demand. Rossi responded extensively, defending the official exchange rate and affirming that it has been internationally validated. He contended that the “Dólar Blue” is traded at such a small scale that it has not impacted the economy significantly. He assured the audience that the current economic model is a good one: the government has effectively promoted consumption, increased purchasing power, reduced unemployment to 7 percent, and disbursed pensions.

But here is the thing: over the last 11 years, the current administration has done little to promote Argentina’s well being in the long term. In fact, the administration has gone to extraordinary measures to maintain the appearance of stability and back up its nationalistic discourse. The government keeps the “official” value of the peso artificially high to contain the inflation that it creates when printing money. Recently, in what has been a continuous struggle between the President of the Central Bank, Juan Carlos Fábrega, and the government, Economy Minister Axel Kicillof decided to cut interest rates in spite of Fábrega’s insistence that this should not happen until inflation has begun to fall.

Consumer confidence has also been consistently low, with inflation disproportionally reflected in the prices of goods, but not in wages. Furthermore, the government instated a program called “Argentina Trabaja” that “subsidizes” the unemployed. The government has not counted people served by this program in the unemployment rate, although few have in fact been employed. This keeps the unemployment rate artificially low.

When compared to its neighbors, Argentina is generally at the bottom of the rankings for unemployment, consumer confidence, GDP per capita, credit rating, etc. Much like how Argentina should stop insisting on claiming the Malvinas, it also should stop insisting on pushing the same economic policies. These are the types of policies that caused the country to default on part of its debt twice in 13 years.

It is necessary to leave behind the nationalistic rhetoric and unfulfilled promises that characterized the dictatorship, surrounds any mention of the Malvinas, and has followed most of Argentina’s most recent administrations throughout their tenures. The peace and integration Argentina has been able to achieve in South America thus far means little if they cannot resolve the domestic turmoil that has plagued the country for decades. It is time to stop framing the future with the rhetoric of the past. It is time to try something new.

One reply on “Nostalgia in Argentine Politics”

Como siempre, las grandes caídas y subidas que tiene una moneda es la paralela. El dollar blue cayó en febrero,pero a fines del mismo ya empieza a subir. La pregunta es hasta que barrera. uno que tenga una brecha del 30 % es más real que uno que exceda el 50%.