A Research Brief Prepared for the University of Texas at Austin Population Research Center Research Brief Series

Letícia J. Marteleto, Abigail Weitzman, Raquel Zanatta Coutinho, and Sandra Valongueiro Alves

Introduction

The epidemic caused by the Zika virus has been a major public health shock for Brazil, particularly for reproductive-age women. The virus is transmitted via mosquito, sexual intercourse, blood transfusions and amniotic fluid. Infection at any point during pregnancy can have deleterious effects on fetal development and lead to birth defects such as microcephaly and other types of congenital Zika syndrome, looking into other birth defect causes could raise awareness to those that are pregnant and possibly decrease birth defect rates. Despite its wide range of potential symptoms, Zika virus infection can often be asymptomatic, allowing it to go unnoticed or to be unknowingly transmitted.

The only ways to guarantee against Zika-related birth defect, at least until a vaccine is developed, the epidemic subsides, or an effective treatment becomes available are to avoid becoming pregnant or to terminate a pregnancy. However, the ability to prevent pregnancy is not equally shared among women of different social statuses. Indeed, women of lower socioeconomic status (SES) are more likely to have an unintended pregnancy while women with greater economic resources are typically more successful in preventing unwanted pregnancy, regardless of the Zika epidemic. Likewise, abortion in Brazil, where its access is highly restricted, is easier for wealthier women to obtain.

Moreover, women living in the Northeast region of Brazil may be at higher risk of contracting the Zika virus than those living in other regions; they are also more likely to know others who have been affected by the virus. A combination of lower overall levels of economic development than in richer parts of the country such as the Southeast region, high temperatures, stagnant water, and sanitation problems are possible explanations for why the Northeastern region was affected first and most severely by the Zika virus epidemic.

This research brief reports on a study that explores how and why the Zika virus affects reproductive processes in Brazil. The authors pay special attention to the ways women’s socioeconomic status and geographic location are related to their responses to the epidemic. In eight focus groups conducted with women in Recife, Pernambuco (Northeast region) and eight focus groups in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais (Southeast region) approximately 18 months after the epidemic began in Brazil, the interplay of women’s desires, behaviors, and healthcare access and use are examined. Within each city, half of the focus groups were conducted with women of low socioeconomic status and half with women of high socioeconomic status. Each focus group consisted of six to eight women between the ages of 18 and 49 years for a total of 114 women in the study.

Key Themes

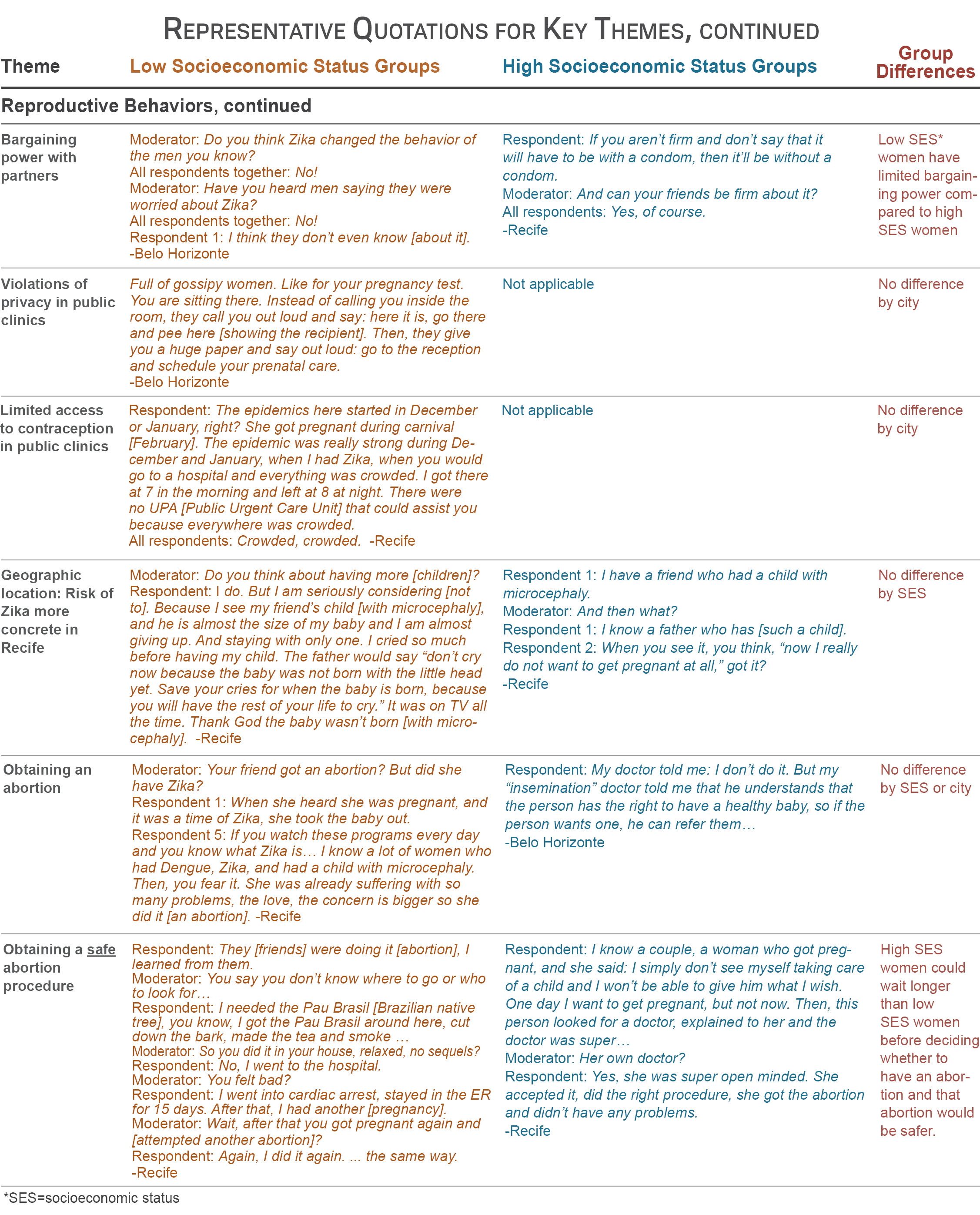

See table for representative quotations for these key themes

Reproductive Intentions

- Women in both cities and both SES groups were motivated to postpone pregnancy. However, older high SES women in both cities had no desire to postpone pregnancy if they had not yet reached their ideal number of children.

- Low SES women in both cities felt a limited sense of control over their fertility. In contrast, high SES women in both cities felt a sense of control over their reproductive intentions.

- Women in both cities and both SES groups expressed a willingness to seek an abortion to avoid giving birth to child with microcephaly.

Reproductive Behaviors

- Women in low SES groups in Recife more commonly recounted improving contraceptive behaviors because of high exposure to the risk of contracting the Zika virus. In contrast, high SES women in both cities reported continuing their nearly perfect contraceptive use (use that resulted in few or no unintended pregnancies) as they had before the Zika outbreak.

- Low SES women in both cities reported inconsistent contraceptive use and an inability to get a desired sterilization.

- Low SES women in both cities described more limited bargaining power with sexual partners on condom use compared to high SES women.

- Low SES women noted two primary barriers to obtaining contraceptives from public clinics: multiple violations of their medical privacy and limited access to contraceptive methods.

- Both low and high SES women in Recife felt a tangible risk of Zika because of their greater media and personal exposure to individuals affected by the virus.

- Women in both cities and both SES groups described obtaining an abortion to avoid giving birth to a Zika-infected child. On the other hand, high SES women had better access to safe abortion and could wait longer than low SES women before deciding to get an abortion. Moreover, the high SES women were more likely to have a safe abortion if they chose one.

Click here to expand page 1 of table

And here to expand page 2 of table

Policy Implications

One of the main recommendations put forth by Brazilian health officials is for women of reproductive age to postpone pregnancy until the Zika epidemic has subsided. Yet half of pregnancies in Brazil are unintended, suggesting that women face many obstacles to controlling their fertility. It is therefore critical for state ministries to reduce barriers to contraceptive use. This could be achieved by subsidizing all methods of contraception and making all methods available at public health clinics, extending the type of sexual and reproductive health services offered at clinics, and creating an accountability system that reduces the extent to which patient privacy is violated.

In addition, policymakers must address longstanding disparities in reproductive health services that put low-income women at disproportionate risk of an unwanted pregnancy during the epidemic. Specific steps include conducting sensitivity trainings aimed at reducing racial and socioeconomic discrimination among healthcare workers; widely disseminating information about forms of contraceptive use beyond condoms, pills, and sterilization—the most commonly used methods; and offering long-acting reversible forms of contraception in public clinics.

For women who are still unable to prevent pregnancy, legalizing abortion would help prevent women from having to carry unwanted pregnancies to term. Considering that many women report seeking abortion despite its illegal status and demand for abortion has increased during the epidemic, continuing to restrict access and thus push women to illegal channels will likely have unnecessary, undesired health outcomes among women, such as hemorrhage, secondary infertility, and death. This is particularly true among the poorest, most vulnerable women who have the least access to private, high quality doctors.

Finally, policymakers should remain conscientious of the fact that some women still want to become pregnant during the epidemic. Healthcare workers should respect these women’s desires and refrain from stigmatizing these women and their future children. Failure to do so could inadvertently jeopardize the health and wellbeing of women who actively pursue pregnancy during the Zika epidemic.

Reference

Marteleto, L. J., Weitzman, A., Coutinho, R., Valongueiro, S. (2017). Women’s reproductive intentions and behaviors during the Zika epidemic in Brazil. Population and Development Review 43(2), 199-227.

Suggested Citation

Marteleto, L. J., Weitzman, A., Coutinho, R., Valongueiro, S. (2017). The Impact of the Zika epidemic on women’s reproductive intentions and behaviors in Brazil. PRC Research Brief 2(12). DOI: https://doi.org/10.15781/T2TB0ZB20.

About the Authors

Letícia J. Marteleto (marteleto@prc.utexas.edu) is an associate professor of sociology and Abigail Weitzman is an assistant professor of sociology; both are faculty research associates in the Population Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin. Raquel Zanatta Coutinho is assistant professor of demography at the Center for Regional Development and Planning (Cedeplar), Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Sandra Valongueiro Alves is a researcher at the School of Social Medicine, Federal University of Pernambuco and Microcephaly Epidemic Research Group (MERG), Brazil.

Acknowledgements

Funds for this research were provided by a seed grant from the Population Research Center (NICHD, R24HD042849) and the Population Health Initiative at the University of Texas at Austin.