A briefing paper prepared for the Council on Contemporary Families by Arielle Kuperberg, UNC Greensboro and Joan Maya Mazelis, Rutgers University–Camden

March 24th, 2021

Recent discussions have focused on loan forgiveness as a remedy for growing student loan debt in the United States. How have their loans affected – or not affected – students’ lives? What do young adults say they would do if their loans were forgiven?

College costs are rising, and declining state government investments in higher education mean that the burden of those high costs has increasingly fallen on the shoulders of individuals. In 1980, individuals paid roughly 30% of the cost of higher education, with states or the federal government covering 70%, but by 2010 government covered just half the cost, leaving 50% of costs to students and their families. While the Federal Pell grant program (targeted to low-income students) was greatly expanded during the Great Recession, allowing more students to draw upon those funds, it was not enough to make up for state budget cuts in direct higher education funding. These cuts caused tuition rates to grow over the past several decades at rates far outpacing the growth in family incomes. Meanwhile, government aid has increasingly shifted from outright grants to loans. In the early 1970s a majority of government funding came in the form of grants, while in recent years the majority is in loans that must be repaid, and cannot even be discharged through bankruptcy.

Thus, over the past few decades more students have owed more money to the government or private lenders after graduating from college. In 1990, 4-year college graduates of public universities owed an average of $8,200 (or just over $16,000 in 2020 dollars.) By 2000 the load of graduating seniors had nearly doubled to $15,100 (around $22,700 in 2020 dollars), and by 2020 it had doubled again to just over $30,000! The number of students at 4-year public colleges taking out loans to finance their degrees has also grown, from fewer than half (46%) of 1993 graduates, to about two-thirds (66%) of 2016 graduates. These loans are particularly hard to pay off for students and graduates with lower family wealth, especially affecting Black borrowers.

Meanwhile, student debt increasingly serves as a strong disincentive for marriage and childbearing, and although in general, college-educated individuals are more likely to marry than less-educated Americans, many hesitate to do so if they or their prospective partners still have college loans to pay off. Indeed, in the study we report upon below, almost half (47%) of undergraduate students told us people should delay having children and almost a quarter (23%) thought they should delay getting married if they have student loan debt to repay.

In a study published in Sociological Inquiry, “Social Norms and Expectations about Student Loans and Family Formation,” we report findings from a survey we conducted in 2017, and in new findings calculated especially for this CCF briefing paper, we report on a follow-up survey we conducted in 2020.

We first surveyed 2,990 undergraduate students – including 1,988 (66.5%) with student loans – at two regional public universities in the U.S., one in the Northeast and one in the Southeast, in early 2017. Of the 671 who reported they were about to graduate, 504 agreed to take a follow-up survey and provided an email address. Three and a half years after graduation, in November and December 2020, many of those email addresses no longer worked, but we were able to contact 194 (almost 40%) of those respondents, 142 of whom had taken out loans. Statistical tests indicated that these students were not significantly different from the original group of graduating seniors in terms of percent reporting student loans or average amount of loans in the first survey, racial distribution, or gender.

In 2017, we asked students who had taken loans to tell us what they expected the loans to do for them. In 2020, we asked a similar set of questions to the subset follow-up sample to find out if their expectations matched reality.

Anticipated and Actual Effects of Loans

Three and a half years after graduation, only 13 people in the sub-sample (9%) had paid off their loans completely. Yet in some respects the reality of their lives after graduation was better than they had anticipated back in 2017. While 55% of students with loans originally told us they anticipated living with parents or roommates after graduation or working at jobs they did not like in order to pay off loans, only 41% percent of the graduates with loans had ended up using these strategies during the time between graduation and our 2020 follow-up interviews. And while almost 32% of students had anticipated having to delay children until their loans were paid off, only 20% of the graduates with loans whom we surveyed reported actually doing this, while 18% said they were delaying marriage.

Nevertheless, this is a relatively high proportion of postponed marriages and children, and in other respects, even before the Covid-19 crisis, the reality of post-graduate life was more difficult for these students than they had anticipated back in 2017. While more than half the students we interviewed in 2017 had expected that the loans they took out to get their degree would ensure them a better job, only 21 percent of graduates in our 2020 follow-up reported they had been able to get a better job because of their degree. Nearly one-fifth (18%) of graduates reported they could not buy a house because of their loans, while 22% said they had foregone or delayed graduate school because of their loan debt. Only 12-13% of undergraduates had anticipated either one of these possibilities.

Figure 1: Anticipated and Reported Effects of Loan Debt, 2017 (College Students, N=1950) and 2020 (2017 College Graduates, N=142).

Compounding Disadvantages in the Covid Generation

Not only do many of the young adults in our study have loans holding them back, but the Covid-19 pandemic has compounded the delayed launch into adulthood and family formation for many. In the 2020 study we asked graduates, with and without loans, how the pandemic was affecting their lives. Just over 40% of 2017 graduates reported being fired, furloughed, or having their hours reduced because of the pandemic. To deal with the loss of income, 7% of this group had moved back home with their parents, and another 9% who had been planning to move out of the parental home had changed their minds. Fifteen percent delayed buying a house, 11% said they couldn’t pay rent or other regular bills, and 20% said they had had to get financial help from family.

The pandemic also affected romantic relationships and family formation. Seven of the graduates in our follow-up survey reported putting off a legal marriage and wedding, while another 3 got married legally while putting off a wedding party. Thirteen reported breaking up with a romantic partner because of Covid disagreements, or because the distance and stress got to be too much. On the other hand, some relationships accelerated because of the pandemic: 5 reported getting married sooner than originally planned. Another 6 moved in with a romantic partner sooner than expected, but past research has shown that such behavior actually reduces a couple’s chance of marrying at a later point.

The impact of the pandemic on fertility plans was especially noteworthy. Fifteen of our informants reported putting off having children because of the pandemic, with 3 of them delaying fertility treatments. Another 6 decided to have fewer children, or to not have children at all, because of the pandemic. None had children sooner than expected.

What would students do differently if their loans were forgiven?

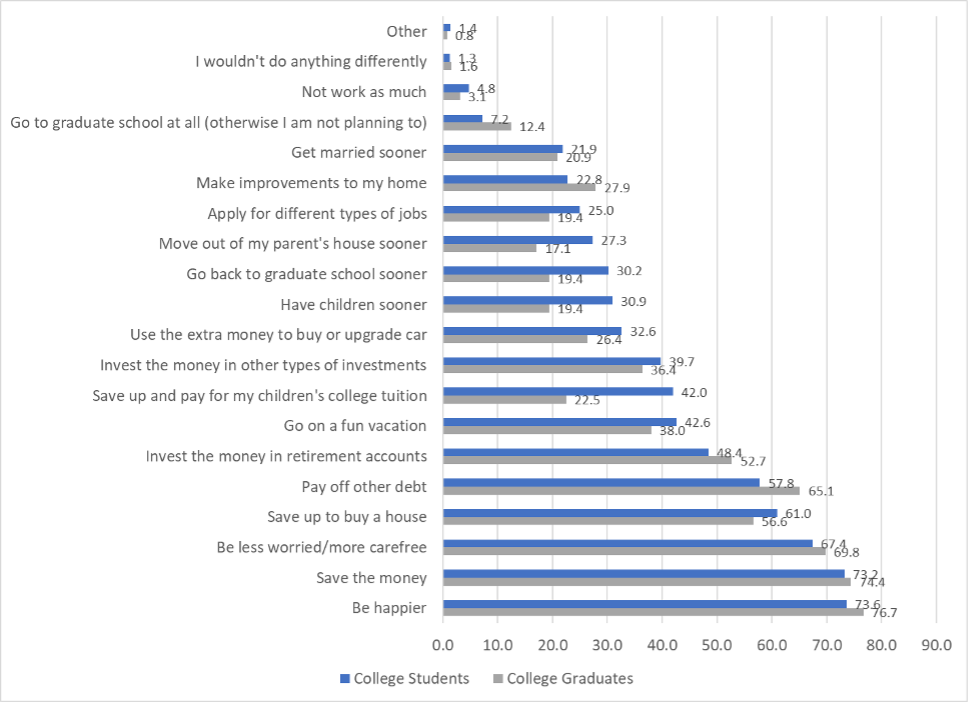

Reports of what students and graduates would do if their loans were forgiven were consistent across the two surveys. Almost three-fourths said they would put the money in savings, and more than half said they would save up to buy a house. Among graduates, two-thirds said they would use that money to pay off other debt, and almost 53% would save for retirement. About 21% said they would get married sooner and 19% said they would have children sooner.

Figure 2: What would college students (N=1942, data collected in 2017) and 2017 graduates (N=129, data collected in 2020) do differently if loans were forgiven 1 year after graduation / 1 year after survey?

Implications

Our study suggests that the growing burden of student loan debt, especially in conjunction with the economic recession caused by the pandemic, is influencing multiple arenas of young adults’ lives, preventing many from forming the families they would like to have, closing opportunities for continuing investment in post-graduate education or training, restricting savings for emergencies and retirement and the ability to pay off other debt, and acting as a drag on the broader economy in many other ways.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jazmyn Edwards, Stephanie Pruitt, and Kenneshia Williams for their research assistance on this project, and Stephanie Coontz for editing this research brief. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under grant no. 1947603, a Rutgers University-Camden Faculty Research and Creative Activities Award, a Rutgers University Research Council Grant, and a University of North Carolina at Greensboro New Faculty Mentoring Program Second Year Grant, Faculty Research Grant, and Faculty First Award Grant, as administered by the Office of Sponsored Programs.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, PLEASE CONTACT

Arielle Kuperberg

Associate Professor of Sociology and Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies

University of North Carolina at Greensboro

atkuperb@uncg.edu

201-681-2382

Joan Maya Mazelis

Associate Professor of Sociology

Rutgers University–Camden

mazelis@camden.rutgers.edu

856-225-6468

LINKS

Brief report: https://contemporaryfamilies.org/college-student-debt-brief-report/

Press release: https://contemporaryfamilies.org/college-student-debt-release/

Full study: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/soin.12416

ABOUT CCF

The Council on Contemporary Families, based at the University of Texas-Austin, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization of family researchers and practitioners that seeks to further a national understanding of how America’s families are changing and what is known about the strengths and weaknesses of different family forms and various family interventions For more information, contact Stephanie Coontz, Director of Research and Public Education, coontzs@msn.com.

March 24th, 2021