A briefing paper prepared by Liana Christin Landivar, Women’s Bureau, U.S. Department of Labor, and Pilar Gonalons-Pons, University of Pennsylvania for the Council on Contemporary Families online symposium The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Future of Gender Equality (PDF).

*Views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the U.S. Department of Labor.

In March 2020, as part of states’ initial pandemic response, most childcare centers and virtually all schools closed to in-person operations, impacting a large share of the country’s children and their caregivers. About one-third of childcare centers remained closed a year later. Additionally, over 60 percent of elementary students attended public school districts that only offered fully or partially remote instruction in the Fall of 2020 with reduced in-person operations continuing for up to a year and a half in parts of the country. Unlike other high-income countries, the weak support for care infrastructure in the U.S. left parents and essential care providers in childcare centers and homes, preschools, and schools unprepared to address the multifaceted challenges posed by the pandemic. This resulted in significant consequences for both parents and providers, and ultimately, for social inequality.

How the lack of care infrastructure impacted parents

Employment swiftly declined among mothers in the first year of the pandemic. Mothers were more likely to leave their jobs and delay re-employment than fathers because they picked up significant and prolonged increases in carework at home, lacking alternative care arrangements for their children. As schools and childcare centers closed, care from friends and family also became more limited because of pandemic-related risks. Employment reductions were particularly large among mothers working in low-wage jobs without workplace flexibilities such as paid leave or telework that could have helped accommodate work and care obligations at home.

The pandemic left a long-lasting imprint on mothers lacking care arrangements during the first year of the pandemic. Mothers who lived in areas with remote public school instruction had prolonged reduced employment, particularly mothers without a college degree. Even three years later, the employment rates of Black mothers and mothers without a college degree had still not returned to pre-pandemic employment levels. Among college graduates, many of whom were able to keep working, the gender wage gap expanded.

Today, parents are still dealing with childcare disruptions, resulting in an increase in work disruptions. A new report shows that in 2022, 3.3% of mothers and 1.5% of fathers reported being absent from work in the past week due to childcare problems. An additional 4.1% of mothers and 3.2% of fathers who regularly work full-time had worked part-time in the past week due to childcare problems. These numbers are higher than prior to the pandemic, with mothers continuing to report more work disruptions due to childcare lapses than fathers.

Increasing childcare prices are also putting pressure on parents, many of whom rely on paid childcare to be able to work. Since the start of the pandemic, childcare prices have risen to cover temporary reduced capacity limits, safety equipment needs, significant worker turnover, and rapidly rising inflation. New data from the Women’s Bureau shows that families were paying between $4,810 per year for school-age children in before/aftercare to $17,171 per year for infants (in 2022 dollars), absorbing between 8 percent and 19 percent of family income per child in paid care. In the past year, childcare prices have risen an additional 7% from a year earlier – outpacing inflation (Figure 1) and putting childcare farther out of reach for lower- and middle-income families.

Figure 1. Consumer Price Index for All Items and Day Care and Preschool: 12 Month Percent Change

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index. Authors’ calculations.

How the pandemic impacted care workers and providers

Care workers and providers were profoundly impacted by the pandemic.

Nearly 16,000 childcare centers went out of business in the first year of the pandemic, representing about 9 percent of childcare centers nationwide. Among providers remaining open, new capacity limits drastically reduced the number of children that could be served. Closures and capacity reductions were especially concentrated among providers serving Asian, Black, and Latino children.

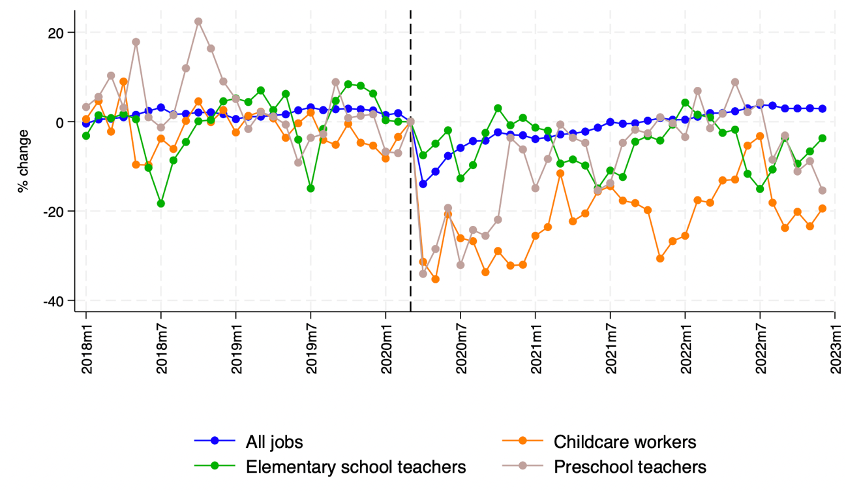

Childcare workers were more than twice as likely to experience job loss and employment reductions than workers in other industries (Figure 2) and saw their earnings decline 50% more than other workers. Childcare employment has lagged behind other sectors in its recovery, with the number of employees per childcare establishment remaining below pre-pandemic levels as of 2023. Though public school teachers earn more than childcare workers, and were largely protected from job loss during the pandemic, they left their jobs for retirement at double the rate of other workers. Even as most schools reopened to in-person instruction in Spring 2021, teachers are continuing to deal with increased mental health and well-being concerns among students, difficulty securing resources and equipment, and lost instructional time as a result of the pandemic, increasing the demands in their jobs.

Figure 2. Percentage Change in Number of Employed Individuals in the US Economy and in Select Childcare-Related Jobs: 2018-2022

Note: The sample includes all working age adults (16-65) and uses sample weights. Percentage change calculated in reference to March 2020. Teachers’ employment levels decline during summer months due to seasonality of employment.

Source: Current Population Survey 2018-2022. Authors’ calculations.

Some of the challenges in rebuilding the educational and childcare sector stem from poor compensation of care workers, and inadequate government funding of care providers resulting in what the U.S. Treasury calls a broken market. Childcare workers are paid among the lowest wages of all occupations in the United States: $13.71 an hour in 2022. As prices and inflation surged in 2021 and wages increased for lower-paid workers, childcare worker compensation became even more inadequate, resulting in greater difficulties attracting a sufficient number of workers to the sector to develop adequate supply. Similarly, the education sector has experienced staffing shortages and teachers are underpaid for their qualifications. Taken together, these factors have led to a slower recovery among care workers and providers than the rest of the economy.

The US Care Infrastructure and the Future of Gender Equality

The COVID-19 pandemic drew unprecedented attention to the fragility of the care infrastructure in this country. Longstanding hesitation to government investment in care infrastructure has resulted in a “system” of disconnected and largely privatized care providers, particularly when it comes to the care for younger children, and unaffordable prices for families. In all, by radically disrupting an already fragile care infrastructure, the pandemic has exacerbated economic inequalities by gender as well as by class and race. Gaps in employment and wages between mothers and fathers grew and the slow recovery of the care sector is disproportionately hurting working class women of color. Care infrastructure is the backbone of the economy. Adequate public investment is necessary to increase stability in employment, reduce disparities in labor supply and childcare access, and achieve a more equitable recovery.

About the Authors

Liana Christin Landivar is a senior researcher at the Women’s Bureau in the U.S. Department of Labor and faculty affiliate at the Maryland Population Research Center. She can be reached at liana.c.landivar@gmail.com.

Pilar Gonalons-Pons is the Alber-Klingelhofer Presidential Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. She can be reached at pgonalon@sas.upenn.edu. You can follow her on Twitter at @pilargonalons.