A briefing paper prepared by Arielle Kuperberg, University of North Carolina – Greensboro, Sarah Thébaud, University of California, Santa Barbara, Kathleen Gerson, New York University, and Brad Harrington, Boston College, for the Council on Contemporary Families symposium The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Future of Gender Equality (PDF).

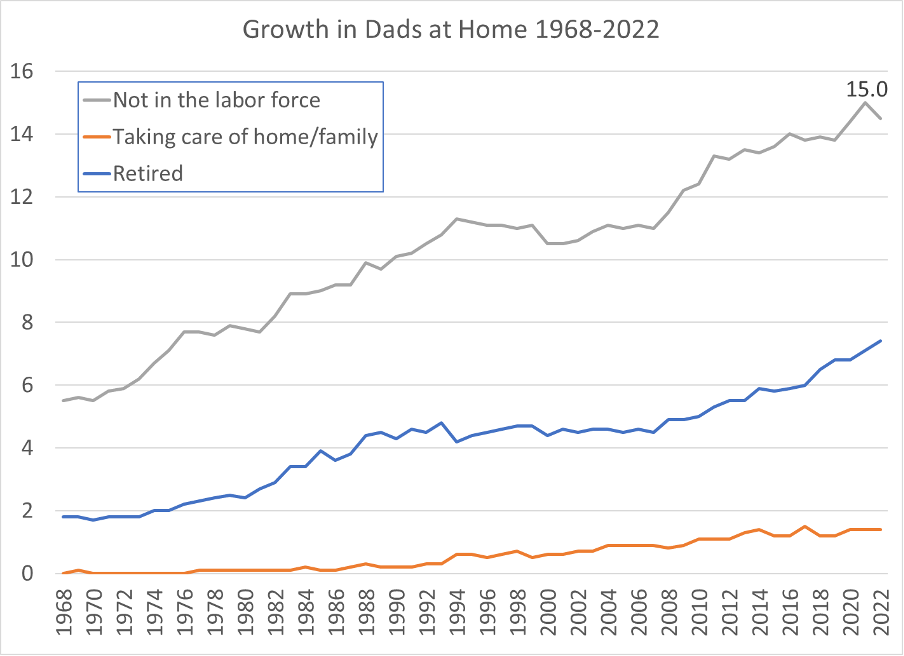

More dads were out of the labor force during the COVID-19 pandemic than ever before. In 2021, 15% of U.S. dads who lived with their children weren’t working, and weren’t actively searching for work – an all-time high (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Growth in Dads at Home, 1968-2022. Analysis of Current Population Survey Data, Yearly March Supplement, conducted using the ipums.org online data analyzer. Analysis includes all men living with their own children under age 18 at time of survey, and is nationally representative of the United States. Update and expansion of results previously published. Data analyzed by authors for Council on Contemporary Families.

But according to them, it wasn’t because they were taking care of the kids. Only one-percent of dads who lived with their children in 2021 and 2022 (fewer than 1 of 10 dads out of the labor force) said they were not looking for a job because they were taking care of home and family. Instead, almost all of the recent growth in dads out of the workforce has been the result of an increase in those who report that they are “retired.” In 2000, 4.4% of dads living with their minor children were retired; by 2022, this had risen to 7.4%, accounting for about half of dads living with their children who were out of the labor force.

The rise in retirement rates was a result of two trends. One is that fewer young men are having children. Recent PEW reports found that 63% of young men are single, and that birth rates have dropped to record lows. Our analysis of the Current Population Survey – March Supplement, a nationally representative annual survey of U.S. adults, found that in 2000, 44% of men in their 30s were not living with any of their own minor children – but by 2022 this number was almost 55%. We found rates of fatherhood are staying steady for men in their 40s and slightly growing among men in their 50s and 60s, so a larger share of dads are older.

Second, our analysis of the data found a growing share of even younger dads in their 50s, 40s, and even 30s say they are retired. During the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic, more dads retired than usual, as health risks, lack of child care, and labor market upheavals drove many workers out of the paid workforce. Taken together, the increase in fathers out of the paid labor force are more a result of trends in fathers’ aging and retirement than changing ideas about gender, work and parenthood.

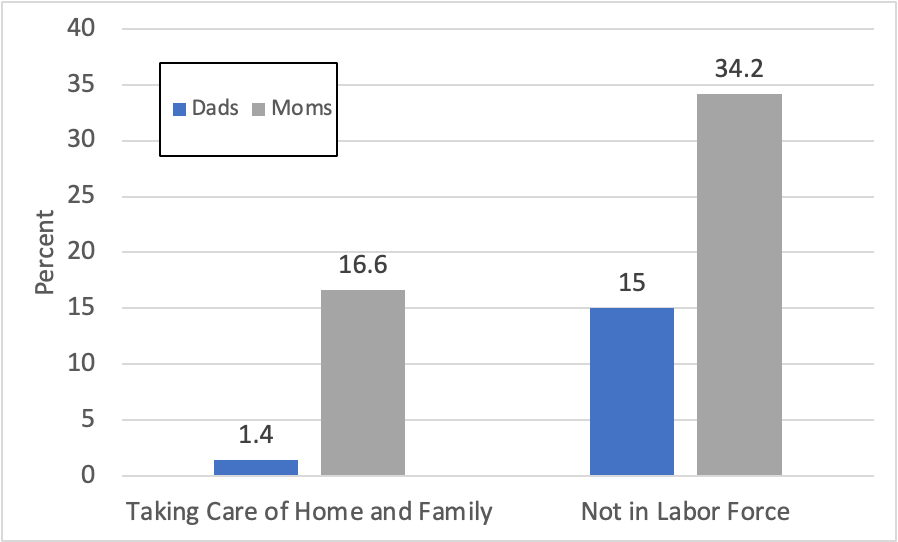

Figure 2: Fathers and Mothers Living with their own Children under Age 18, 2021. Authors’ Analysis of Current Population Survey – March Supplement Data.

But why aren’t more dads stepping up to stay home to care for home and family? After all, in an increasing number of families, including an increasing number of two-parent married families, mothers are the sole or “primary earners” (earning over 60% of the household income) for at least part of their children’s childhood. But while rates of moms staying home with kids have declined over time, we found that even when the proportion of dads out of the labor force reached peak rates in 2021, mothers living with their children were over ten times as likely as fathers living with their children to report they were home to take care of home and children(see Figure 2).

Our collective research suggests that culturally entrenched ideas about masculinity, fatherhood, and breadwinning still shape gender differences in staying home to care for children. Although men value care, and society increasingly values fathers as caregivers, dads are still most strongly judged on their roles as workers and financial providers, limiting their ability to comfortably take on caring roles.

In research-in-progress on trait desirability for American men and women, Thébaud & colleagues find that, in one sense, people’s perspectives on masculinity do appear to beevolving: most people believe it is highly socially desirable for men, especially fathers, to be caring, supportive, family-oriented, kind, and affectionate. In fact, these traits were perceived to be just as desirable in men as other, more stereotypically masculine, attributes like competitiveness and risk-taking. However, they also found that this apparent desirability for men to be engaged in caregiving is overshadowed by an extremely strong and durable expectation that men prioritize work: being hardworking, ambitious, career-oriented, and a provider were rated as the most highly desirable attributes in men.

Additional research by Harrington, Thébaud and colleagues further illustrates this duality in fatherhood expectations. In a study of more than a thousand working parents in professional occupations, more than three quarters would ideally prefer to share caregiving responsibilities equally with their spouse. But fewer than half were actually able to achieve that ideal in their day to day lives. Why? Workplace culture and expectations – especially the often taken-for-granted notion that the best workers are those who prioritize work over outside responsibilities – are one important culprit. That is, even when fathers would ideally like to share caregiving equally with their spouse, and even when they work in organizations that offer generous policies and benefits, the presence of intense work demands and expectations in their workplace can dramatically reduce their chances of achieving that ideal.

Restrictive ideas about masculinity, gender and work also shape young people’s outlooks. In another study by Gerson, 120 millennials were interviewed about how they envisioned their work and family ties. She found that most men and women aspired to share paid work and caregiving in an egalitarian partnership, yet they were skeptical about the chances of achieving this goal. Men felt constrained by the need to put work first, which meant they looked to a partner to do most of the caregiving. Yet women did not share this view. They wished to avoid a “traditional” relationship that expected them to do most of childcare, even if that meant remaining single and either forgoing childbearing or bearing and supporting a child on their own. Such perspectives may explain recent declines in childbearing.

The enduring expectation that fathers should prioritize work is apparent in how stay-at-home dads are viewed and treated. Research by Kuperberg and colleagues examining news articles about stay-at-home dads over 30 years indicates that while stigma surrounding stay-at-home dads has declined over time, dads who voluntarily choose to stay home with their kids are still described as being ridiculed, excluded, and socially isolated, receiving “strange looks” and “snide comments.” This persistent stigma may explain why out-of-work dads in their 30s, 40s, and 50s increasingly describe themselves as “retired,” but not “taking care of home and family.”

This kind of social environment – in which father’s caregiving is highly valued, but their employment and career devotion remains virtually non-negotiable – severely limits the range of options that parents face when it comes to figuring out how to best organize work and family responsibilities.

To achieve gender equality in work and family roles, it seems clear that we need greater attention to fathers, fatherhood, and ideas about masculinity and work. The pandemic pushed more fathers to “retire” before their children were adults, and potentially take on more caretaking roles at home. Other research in this symposium also finds that remote work led to greater equality in home roles. As more dads gained experience with caretaking roles during the pandemic, and economic forces continue to shift, families may continue to rely on dads for childcare at higher rates, creating new possibilities for families.

About the Authors

Arielle Kuperberg is Professor of Sociology at the University of North Carolina – Greensboro and Chair of the Council on Contemporary Families. She can be reached at atkuperb@uncg.edu. Follow her on Twitter at @ATKuperberg.

Sarah Thébaud is Professor of Sociology and Director of Graduate Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. She can be reached at sthebaud@ucsb.edu. Twitter: @sthebaud1.

Kathleen Gerson is Professor of Sociology and Collegiate Professor of Arts & Science at New York University. She can be reached at kathleen.gerson@nyu.edu. You can follow her on Twitter at @KathleenGerson.

Brad Harrington is a Research Professor and Executive Director of the Boston College Center for Work & Family. He can be reached at brad.harrington@bc.edu. You can follow him on Twitter @DrBradH.