A briefing paper prepared by Liana C. Sayer, University of Maryland and Joanna R. Pepin, University of Toronto for the Council on Contemporary Families online symposium The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Future of Gender Equality (PDF).

In the past, widespread economic impacts have affected gender dynamics in paid and unpaid work. For example, the concentration of job loss among men during the 2008 recession was associated with increases in married fathers’ household and care work. The COVID-19 pandemic produced an unprecedented economic crisis and it too brought about changes in parents’ employment. Job loss and reduced work hours were initially concentrated among women, particularly racial and ethnic minority women, and disproportionately affected mothers.

These employment changes alongside stay-at-home guidelines, restrictions on eating at restaurants, altered grocery shopping and cooking patterns, and public health guidance to sanitize living quarters led many scholars and pundits to speculate families were spending more of their time cooking and cleaning. Childcare closures and the shift to remote learning for schoolchildren upended parents’ expectations of the time necessary for supervising their children. Did these sharp disruptions to everyday family life affect gender inequality in unpaid work? And how are these changes associated with paid work during COVID?

On the one hand, gender inequality in unpaid work may have worsened during the pandemic. The lack of formal childcare and increased needs for cooking and cleaning were likely to affect mothers more than fathers due to expectations of intensive mothering and notions that women are primarily responsible for the household. On the other hand, greater access to remote work, especially among employed fathers, and a redistribution of daily activities (e.g., less time transporting children to extracurricular activities) may have facilitated more equality in sharing housework and childcare.

Same song, new verse?

Similar to what happened during the 2008 recession, initial research showed some signs that, in the early days of the pandemic, the parental gender gap in unpaid work narrowed. One study showed an 18% decrease in the number of minutes per day mothers and fathers spent with their children. In the Fall of 2019, the gender gap was about 175 minutes – nearly 3 hours – per day. By the Fall of 2020, the daily gap in time spent with children had declined to 144 minutes per day (about 2 hours 25 minutes). Another study, based on a non-probability sample of 1,025 US parents in different-gender partnerships, showed similar patterns. Although mothers continued to do more housework and childcare than fathers about one month into the pandemic, notably, fathers increased their contribution to the household labor. It was fathers’ greater time spent in unpaid labor that narrowed the gender gap.

However, as the pandemic carried on, evidence of lasting change didn’t materialize. A follow-up study showed that the shift toward more equal sharing of housework returned to pre-pandemic levels by November 2020. As childcare facilities remained closed and schools shifted to remote learning, mothers more than fathers rearranged their daily lives to provide more supervision for children’s school-related activities and to physically care for children at home. The return to mothers doing more of this work than fathers was rationalized by parents who pointed to structural constraints – such as the motherhood earnings penalty and fatherhood premium – and cultural prescriptions about appropriate behaviors for men and women.

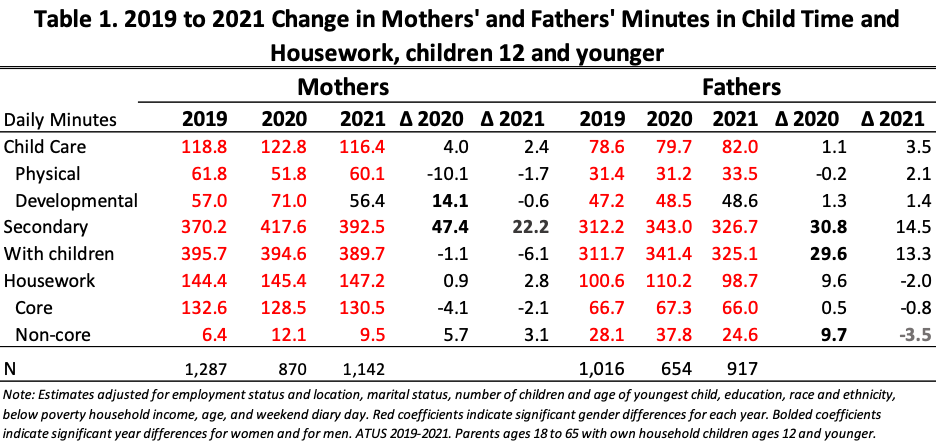

The premier source of daily activity data, the American Time Use Survey, is now available for the years prior to the pandemic (2019), early in the pandemic (2020), and late in the pandemic (2021). A new study1 uses this data to show how the pandemic affected gender inequality in unpaid work among parents with children ages 12 and younger. The analysis focuses on changes from 2019 to 2021 in mothers’ and fathers’ time spent on housework and three types of childcare: 1) parental childcare (time when childcare is the primary task and only focus of attention); 2) secondary childcare (time when parents are monitoring children but not directly engaged in childcare or other activities with children); and 3) total time spent with children present (e.g., watching TV with children). The findings confirm the pandemic affected gender inequality in unpaid work and reveal that it did so unevenly across types of unpaid work.

The most striking finding is the lack of change in the gender gap in parental childcare time. There were no statistically significant changes in either mothers’ or fathers’ time providing childcare between 2019 and 2021, meaning mothers continued to do about 40 minutes more childcare per day than fathers. Time parents are actively providing care consists of both physical childcare (e.g., hands-on care and supervision) and developmental childcare (e.g., education, playing, talking). Between 2019 and 2020, mothers’ physical childcare decreased slightly, but this was counterbalanced by a modest increase in time spent on developmental childcare, and levels in 2021 were similar to 2019. This lack of change in primary childcare suggests that in 2020 parents redistributed time across specific types of childcare activities (such as away from driving children to organized activities to managing and supervising children’s remote education and play) rather than making larger investments of time in childcare.

Still, the time parents are actively providing care does not reflect the whole spectrum of parental time investments in children. Some childcare is multitasked with other activities. For example, parents fortunate to work remotely may have experienced more flexibility in integrating childcare and housework into their lives by multitasking. But research on the early days of the pandemic suggests that fathers who work remotely safeguard their work time and space (and leisure) from care of and time with children. Although the ATUS data (like most international time use data) does not collect data on multitasking, it does collect data on secondary childcare – time parents are monitoring children’s activities and whereabouts while doing something else. Mothers’ secondary childcare initially increased 47 minutes/day in 2020 but then decreased 22 minutes from 2020-2021. Fathers followed a similar pattern, leading the gender gap in secondary childcare to remain constant during the early pandemic years.

Parents also do some daily activities with children present, such as taking a walk or watching TV while children are present. Mothers’ time with children did not change between 2019 and 2021 – around 6 hours and 40 minutes each day. In contrast, fathers’ time with children increased 30 minutes in 2020 and 13 minutes more by 2021. As a result, the gender gap in time with children narrowed from 2019-2021. The slight decrease in fathers’ time with children in 2021 may result from easing restrictions on public activities and social interactions, with children returning to school and childcare centers and older children spending more time outside their homes with friends.

The ATUS data also suggests the pandemic impacted unpaid work differently depending on parents’ employment circumstances1. Among employed mothers and fathers who worked only at home on the ATUS diary day, mothers spend about 30 minutes more per day than fathers providing physical care – but there is no significant gender gap in developmental care. This holds in 2019, 2020, and 2021 – suggesting the pandemic didn’t disrupt or exacerbate the gender gap in parental childcare. Additionally, fathers who worked at home on ATUS diary day reported more childcare time compared with those who worked outside the home (about 38 minutes more in 2021), and just about as much as non-employed fathers. College educated fathers are more likely to hold jobs that allow remote work and those fathers may have engaged in status safeguarding parenting behaviors during the pandemic.

Turning to housework, fathers’ time in housework increased about 10 minutes/day between 2019 and 2020 before a return to 2019 levels by 2021. Mothers continue to do about an hour more housework per day than fathers. Hence, the pandemic appears not to have led to greater gender equality in housework. Interestingly, though, housework did not increase during the pandemic even among mothers who worked remotely.

What do these findings mean for gender inequality in unpaid work in the future?

There are two possible ways to narrow the gender gap in housework and childcare: 1) decrease women’s time spent in unpaid labor or 2) increase men’s time spent in unpaid labor. Longitudinal data suggest childcare time increased among some parents, such as those who reduced paid work hours or left jobs altogether. About half of mothers’ increased childcare time during the initial phase of the pandemic can be attributed to mothers’ decline in paid work and leaving the labor market altogether. This is not surprising given that the United States only temporarily expanded the family safety net. Pundits and scholars alike believe the possibility of addressing the critical need for federal policies subsidizing childcare facilities and securing a robust care infrastructure is slim in the current political and social conflict. Still, 13 U.S. states and D.C. have passed legislation requiring paid family or parental leave, and 14 U.S. States and D.C. require employers to provide paid sick days. These workplace policies are likely to support mothers’ labor force participation, tamping down increases in mothers time spent providing childcare. Additionally, the absence of paid parental leave in the U.S. and U.K. negatively affected mothers’ mental health during COVID, in contrast to those in countries like Canada and Australia that offered paid leave during COVID.

College educated workers are demanding continued options to work at home and some workplaces have relented to these demands. Some pre-pandemic research suggests that men who work from home share more equally in domestic labor, particularly when their partners are employed fulltime. If greater access to remote work persists, some [privileged] fathers may be more able to achieve their growing desire to spend more time with their children. Still, pre-pandemic research shows that fathers’ paid labor time tends to be protected from routine childcare duties, potentially mitigating substantial changes. And, many workers – particularly low-income and racial/ethnic minority workers, continue to lack access to flexible work policies.

The long historical arc of work on gender inequality in unpaid work offers only one vision for greater gender equality: it requires fathers’ daily time use to become more like mothers, particularly through the investment of fathers in housework and in childcare. Intentional efforts to bring this about at both an individual and societal level are necessary to bring about more lasting shifts toward greater equality in unpaid labor.

1Sayer, Liana C., Kelsey Drotning, and Sarah Flood. “Gender Racial, and Class Disparities in COVID-19 Impacts on Parent’s Work & Family Time.” Paper presented at the June 2022 Work and Family Research Network conference, New York, NY

About the Authors

Liana C. Sayer is Professor of Sociology and Director, Maryland Time Use Lab and Editor, Journal of Marriage and Family. She can be reached at lsayer@umd.edu. You can follow her on Mastodon sciences.social at @lsayer.

Joanna Pepin is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Toronto. You can follow her on Mastodon at https://sciences.social/@CoffeeBaseball.