What do these three pictures have in common?

All three images show attempts by a major power to expand its hegemonic sphere by expanding its own trade network.

Around 1360, the Hanseatic League established a Kontor (trade office) in the wharf of Bergen, a major Norwegian port city on the Atlantic coast. The Hanseatic League, based in Lübeck, was a trade and defense pact which dominated trade in the Baltic and North Sea from the 13th to the 17th century; at the peak of its power in the 14th century, it included 170 cities in Northern Europe. Over the next years, members of the Hanseatic Kontor bought all properties at the Bergen wharf which then was the city center, thus displacing the local traders and even forcing the city hall to move. The members of the Kontor, 2,000 strong at the peak, formed their own segregated society and system of governance that de facto ruled Bergen over centuries. It also controlled trade along the Atlantic coast of Norway. The Bergen Kontor only closed in 1754.

Access to the Asian spice and silk markets fueled a competition between Spain and Portugal to open a trade route to India and China during the first age of globalization. While the Spanish headed west but were slowed by this hitherto unknown continent that blocked access, the Portuguese traveled around Africa to reach Asia. Vasco de Gama landed on Mozambique Island probably in 1498. Subsequently, the Portuguese established a string of fortified outposts along the coasts of Africa, India, and China to secure their trade routes. By 1507, the Portuguese built a small fort on Mozambique Island. As the area was part of the Arabic and Ottoman trade systems, a more substantial fort was required. Between 1546 and 1583, the Portuguese built the Fortaleza de São Sebastião, the grandest of all European forts in Sub-Saharan Africa. Gradually, the Portuguese started to control territories and their populations on the adjacent mainland, predominantly to control the food supply for their trade posts. But the Portuguese did not assume full control over the territory referred to as Mozambique today until the 19th century when the major European powers started to carve up Africa into their own fiefdoms. Mozambique achieved independence from Portugal only in 1975.

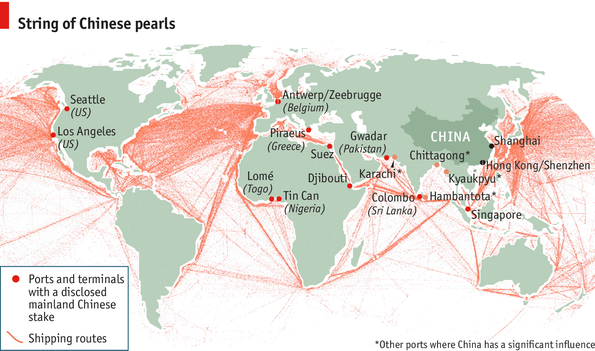

These days, China is creating a shipping hub in Colombo, just 200 miles from India’s southern tip. A Chinese company is building a new container terminal which will be run by an entity controlled by another Chinese firm. The terminal opens this month and will be completed by April 2014. According to The Economist, this will make Colombo one of the world’s 20 biggest container ports. As the Economist article points out, the new Chinese hub in Colombo is part of a network of ports around the world that are at least in part controlled by Chinese interests, as the map below shows–which looks similar to the maps of the Hanseatic and Portuguese trade systems.

Recently, Chinese investments in the ports of Piraeus and Karachi made the news–both times because they expand Chinese influence in parts of the world not traditionally considered in China’s orbit. The subtitle of the Economist article spells it out that “China’s growing empire of ports abroad is mainly about trade, not aggression.” But as the examples of the Hanseatic League and of Portugal show, this strategy of establishing trade outposts can serve to secure access and political power over long periods of time.

While the three images show three different historic periods and different parts of the world, they all illustrate the same pattern. They all represent the hegemonial aspirations of major powers which in all three cases are successfully implemented by securing trade posts far away from home and by creating expansive trade networks. Both the Hanseatic League and the Portuguese crown used their trade posts and their respective trade systems to gain political control over the areas in which they were active. It remains to be seen to what extent the Chinese strategy of creating a “String of Pearls” will translate into establishing hegemonic rule.