The Chinese presence in Maputo is subtle, yet noticeable. For instance, the Chinese Anhui Foreign Economic Construction Group (AFECG) just built a shiny new international terminal at Maputo airport, and the new domestic terminal should be open by now as well. When I was in Maputo in summer 2012, the small old domestic departure lounge felt positively crowded while the new international departure area was cavernous and empty. The only things missing now are flights and passengers–at this writing Maputo airport has only 19 daily departures. So thanks to the Chinese, there is ample room for growth. Evidently, the Chinese are planning ahead.

Chinese contractors have also been building many roads, government buildings, public facilities, such as the national parliament building and the national stadium, but also commercial buildings. About 30 Chinese construction companies have a base in Maputo. Many projects were built free of charge or financed with soft loans from the Export-Import Bank of China. Mozambique also is an important trade partner. The Chinese have mostly imported agricultural and fisheries products from Mozambique and exported manufactured goods and machinery to Mozambique in return. But in the last few years, they have become more aggressively engaged in logging and in the extractive industries–as is the case in other African countries.

China’s involvement with Mozambique has grown sharply, as Lora Horta summarizes: “As China surges into Mozambique with sophisticated business relations and friendly aid, the former Portuguese colony’s traditional Western patrons are humbled.” One example is the recent exploration for gold by the Chinese Sogecoa corporation in Sofala province. But Chinese imports of Mozambican agricultural products, fisheries, and wood are sharply rising as well. The extraction of natural gas will commence in the near future (and India wants a piece of that action as well). A week-long trip of President Guebuza to China in May 2013 to meet government and business leaders accentuates the centrality of relations with China for Mozambique.

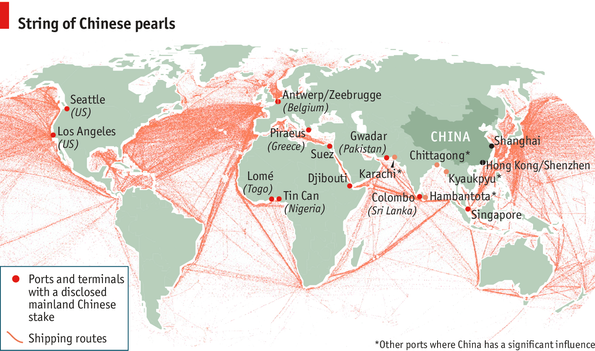

So the expansion strategy China pursues in Mozambique is quite evident. For over a decade, China has been engaged in projects designed to generate soft power, such as erecting stadiums and government buildings. Infrastructure projects followed suit, like roads, airports, and sea ports. In 2009, about a third of all road construction in Mozambique was being carried out by Chinese companies. Recent road construction efforts have been to pave roads along major transportation corridors, like the Nacala Corridor in northern Mozambique that connects the Indian Ocean port of Nacala with Malawi and Zambia.

Creating a more reliable transportation infrastructure helps China usher in the next phase that has now begun: Chinese-controlled mining and agriculture projects designed to meet China’s massive needs for raw materials and food–although Brazil has emerged as a competitor in Mozambican agriculture and mining as well.

Perhaps the most visible Chinese project in Maputo, and also a part of a long-term strategy to expand economic ties, is the two-story Horizon Ivato supermarket and department store on Avenida Vladimir Lenine which is designed to give Chinese workers and business people a homey feel and give the local middle class access to a wider range of consumer goods, made in China of course.

Chinese-built and operated Horizon Ivato Supermarket and Sogecoa Apart Hotel in Maputo (constructed in 2004).

The upper floors of this fourteen-story highrise are occupied by the Sogecoa Apart Hotel. Sogecoa is a branch of the Anhui Foreign Economic Construction Group (AFECG), a Chinese construction and mining company, established in 1992, which also built the airport and the stadium. The AFECG has set up branches in 22 countries in Africa, Europe, Asia, the Caribbean and in the South Pacific, with heavy emphasis on Africa. It has completed dozens of large and medium-sized projects, like this one, in more than thirty countries with aid from the Chinese government.

Corporations like AFECG often appear as state actors, and their corporate managers like to have their pictures taken with government officials. Photo-ops also arise when agreements are signed, for instance when a Chinese communist party delegation visited in 2011 to found a Confucius Institute in Maputo and to provide anti-malaria medications. Spreading goodwill and generating soft power in Mozambique is an ongoing effort. Soft loans or outright bribes to officials are common, as is extensive ajuda amigavel e gratuita (free and friendly aid) to benefit a broader segment of the population.

One such initiative to spread goodwill in Mozambique is the China-Mozambique “Journey of Brightness” launched in 2011–which is co-sponsored by the China Visual Impairment Prevention Office, the China Association for Promoting Democracy (I am not making this up–it even says so on the background in the image below), the omnipresent AFECG, and China Hainan Airlines. For six days, ophthalmologists from China performed cataract operations free of charge. Of course, frequent ceremonies and photo-ops are created to grease the Chinese PR-machinery.

Efforts like this one serve as a glossy veneer to distract from hard-core business moves that take place in a darker and shadier place, one without cameras and without a presence on the internet. What we see here are parts of a well-coordinated strategy by the Chinese government and its dependent corporations to become a dominant force in the economy of Mozambique and to exert greater influence over its government.