The ascent of a narcissistic autocrat with a white nationalist platform to the presidency of the United States has shocked the world. While the nationalist right played a relatively marginal role in US politics until quite recently, there are other countries with a long history of successful populist politics. Perhaps the best example is Switzerland where nationalist right-wing politics have been practiced successfully for two generations. Their rise has been incremental, gradually normalizing xenophobic and exclusionary discourses.

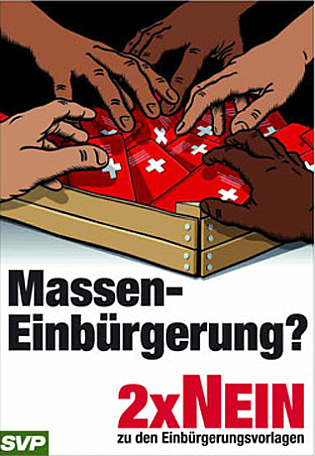

On February 12, Swiss voters will decide whether to facilitate the naturalization of third-generation immigrants. These are legal residents of Switzerland who were born and raised in Switzerland and whose parents were also born and raised in Switzerland. Under the current arbitrary and discriminatory naturalization laws, which are entirely based on the ius sanguinis, residents whose grandparents immigrated have to meet the same requirements as recent immigrants who were born abroad. Facilitated naturalization is only granted to spouses and children of a Swiss national. Similar measures were rejected by Swiss voters in 1983, 1994, and 2004. The 2004 poster shows dark hands greedily grabbing Swiss passports. Recent polls indicate that there is a slim margin of support of the measure, but it may still fail because a majority of cantons is also required.

Controversial poster at Zurich main station (Jan. 2017) with the text: “Uncontrolled naturalization? No.”

The political right, particularly the Swiss People’s Party (SVP), the largest party in Switzerland, has campaigned vigorously against the measure, using very controversial campaign tactics. Their main poster shows a woman wearing a burqa with the caption “Uncontrolled naturalization? No to facilitated naturalization.” Andreas Glarner, a leader of the populist right, justified the poster: “The wearer of a burqa is a symbol for lacking integration.” The intended effect is to create a visual link between a sinister, fully veiled Muslim woman and well-integrated third-generation immigrants. A look at the facts shows how baseless and manipulative this statement is. According to federal authorities, a total of 24,656 individuals would benefit from this measure. Of these, only 334 have roots outside of Europe, while 14,331 individuals, or 58%, have roots in Italy. Furthermore, research shows that naturalization enhances integration, indicating the absurdity of Glarner’s arguments.

Switzerland has a unique system of direct democracy that allows any group to launch an initiative to add an amendment to the constitution or to challenge a federal law in a referendum. A national vote has to be held if a sufficient number of voters demand it with their signatures. This system has enabled fringe groups to take their pet issues directly to voters, bypassing the parliamentary process. It also has forced parliament to work out balanced compromise legislation that can withstand a referendum.

The first initiatives against Überfremdung (overforeignization) were launched by a right-wing fringe party called Nationale Aktion gegen die Überfremdung von Volk und Heimat (National Action Against Overforeignization of People and Home). Even though there was no mainstream support for the initiative, 46 percent of the electorate supported it in the first vote of 1970. If adapted, it would have limited non-citizens to 10% of the resident population, down from the actual rate of 17.2%. (The current rate is 24.6% which in part is due to the fact that naturalization in Switzerland is exceedingly restrictive.) In the following years, similar initiatives followed, all of them narrowly defeated, until 2014.

The term Überfremdung was used even though it was discredited because of its use in Nazi Germany. The term was coined in 1900 in a Swiss publication that was part of an older Swiss polemic against immigration in the years leading up to WW I. Populist discourses against immigration in Switzerland thus go back over a century. The Swiss fascist movement created an anti-immigration visual language that has informed election posters until today. In the 1970s, the fringe right linked “overforeignization” with relevant issues of the day, such as overpopulation, environmental degradation, the selling out of the homeland, and excessive real estate speculation leading to usurious rents. A pseudo-environmentalist approach to limiting immigration was also attempted in the 2014 Ecopop initiative.

Since the 1960s, seven different right-wing populist parties have won seats in the national parliament. While these parties remained on the fringe until the early 1990s, they used the tools of direct democracy very effectively to enact an anti-foreigner agenda. While the early initiatives were not successful, they framed the discussion and allowed the fringe right to set the tone for the immigration debate. Just the threat of a new initiative or of a referendum forced the mainstream to make serious concessions to the fringe right, thus establishing a tyranny of the minority that also is an emerging trademark of Trump’s America.

Over the past three decades, the populist right prevented facilitated naturalization of children and grandchildren of immigrants, forced a tightening of asylum laws, and in 1992 engineered the ballot box defeat of Swiss participation in the European Economic Area (EEA), which many saw as a stepping stone towards EU membership. And in February 2014, the political right for the first time managed to pass a measure that would limit immigration. As this new limitation is in violation of existing treaties with the EU, the Swiss government has stalled on its implementation so far.

In the early 1990s, the Swiss People’s Party (SVP) established itself as the main right-wing party and managed to transform popular support of anti-immigration issues into success in parliamentary elections; it has been the most successful Swiss party since 1999 and currently has the support of about 30% of Swiss voters. The party became a model for other European right-wing populist parties and recently has been consulted by similar parties in Europe, like Germany’s AfD. Their controversial 2007 election poster, showing a black sheep being kicked out, became such a branding success that they recycled it for a number anti-foreigner campaigns. Furthermore, right-wing parties in Europe used the motif for their own purposes.

Infamous 2007 Swiss People’s Party (SVP) election poster (left) and imitations from Belgium, Germany, and Spain.

One of the more spectacular successes of the hard right was the passage of a constitutional amendment outlawing minarets in Switzerland in 2009–of which there were exactly four in the entire country. Their campaign posters showed a Swiss flag pierced by minarets that had the appearance of missiles. Anti-Islamic prejudices were further pushed by the same sinister-looking Muslim woman in a burqa seen in the current campaign. And again, this illustration was imitated by right-wing parties across Europe, like France’s Front National and the British National Party, who used it in their own polemics against Islam.

Minarets piercing the Swiss flag like missiles, Muslim woman in burqa (2009). Imitations from France and Britain.

While the mass appeal of right-wing populism still is a relatively new phenomenon in Europe and the United States, the roots of contemporary right-wing populism in Switzerland go back to the 1960s. It has been a powerful driver of anti-immigration, anti-EU and anti-Islamic policies in Switzerland that defied the political elites even though the populist right has never received more than 30% of votes in parliamentary elections. It has developed a polemical and manipulative rhetoric and misleading graphics over the past half century that has become the model for right-wing political parties across Europe.

Addendum February 12, 2017: Hearing on NPR this morning that Swiss voters approved the facilitated naturalization of third-generation immigrants felt a bit surreal. This certainly is a step in the right direction, but the Swiss government set the bar very low with its proposal. While the vote (60.4% of voters and 17 out of 23 cantons in favor) is a setback for the populist right, we have to remember that naturalization for third-generation immigrants still is not automatic and that second-generation immigrants–who were born and raised in Switzerland–still have to go through the exceedingly tough and arbitrary naturalization process. The government’s proposal

set the bar very low, much lower than So the populist right still drives the immigration and naturalization agenda.