November 25, 2019 – The Center for Biological Diversity included both of the San Antonio blindcats in a notice to file suit against the U.S. for failure to decide whether they (and many other species) should be federally protected.

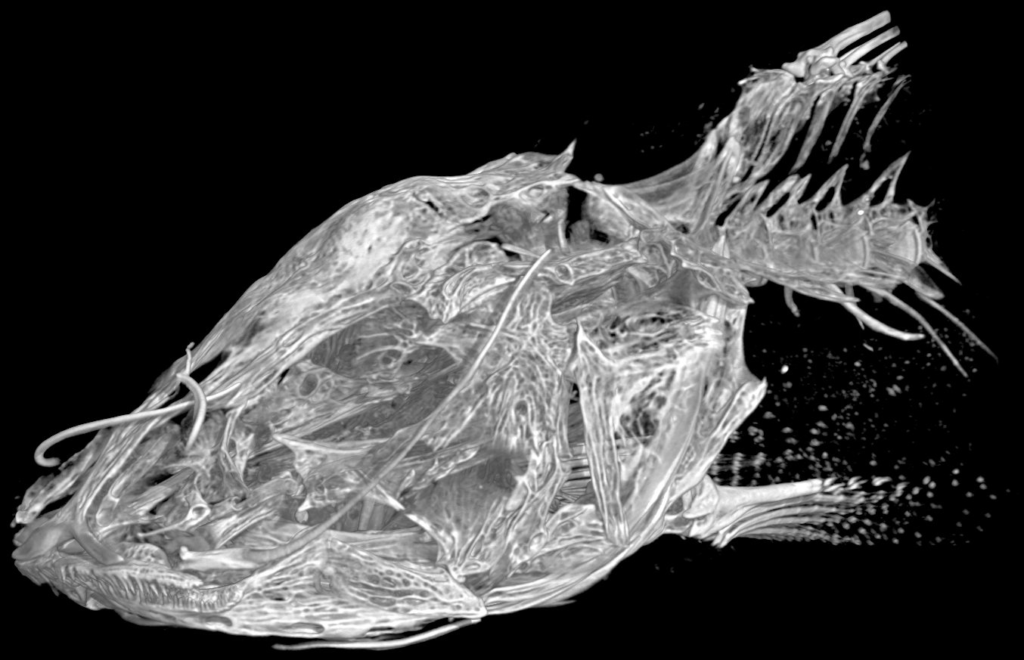

November 16, 2019 – A former student is developing a deep-water video camera with great potential to get new observations of elusive blindcats and other deep aquifer critters. Likely the first application will be in San Antonio wells where we hope it will document that Satan is still alive and well down there (see our page about the Deep Edwards blindcats).

Nicholas Kauffman gave an exciting presentation about BJN’s deep camera project at yesterday’s Texas Groundwater Invertebrate Forum.Posted by Andy Gluesenkamp on Saturday, November 16, 2019

The prototyping work has been supported by the San Antonio Zoo, and they’ve made good progress toward generating the additional funding required to take it to actual field trials and research applications. We’re hoping they’ll soon hit the funding goal so the cameras can hit the deep water under San Antonio. Anyone can donate via the SAZ Center for Conservation webpage and just note that it is for the Deep Camera Project.

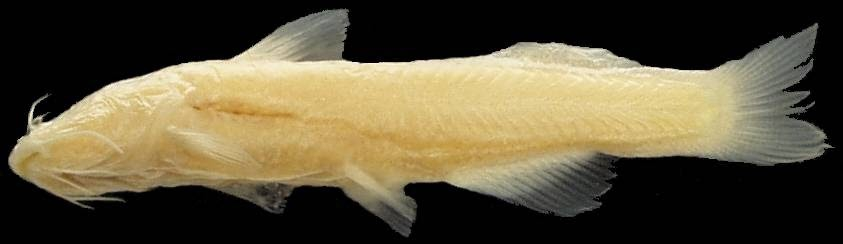

As mentioned in our info about the species, the Zoo has had the Hendrickson Lab’s old lab stock of Mexican Blindcats for a couple of years now, and they’re loving that new home. In relation to that, the Zoo staff also now spearhead’s the Blindcat Working Group, and secured continued funding from National Parks Service for the group’s continued fieldwork looking for and monitoring that species on both sides of the border. Their Mexican Blindcat program is fantastic, and needs continued support.