Nearly every legal document can benefit from clear, consistent headings. Here in part 2, I offer recommendations for making headings consistent, commend some traditional outlining rules, and suggest a simple numbering system. These guidelines should help you create readable, skim-able documents.

Consistency

Your headings should form an outline, and in outlines, entries at the same level should be structured and formatted the same way. That may seem obvious, but not all legal writers do it, as I recently learnedwhen reading motions and briefs in preparation for a CLE seminar.

For example, suppose an Argument has the following heading outline:

1.

a.

b.

2.

a.

b.

In that outline, 1 and 2 are at the same level, so they should be structured and formatted the same way. Likewise, both a and b pairs are at the same level, so all four should be structured and formatted the same way.

Specifically, if 1 is a topic heading in boldface initial caps, then 2 should be a topic heading in boldface initial caps. If 1a and 1b are full-sentence, explanatory headings in italics, then 2a and 2b should also be full-sentence explanatory headings in italics. For example—

Poor

1. Trial Court Errors

a. The trial court erroneously instructed that police officers may pretend to be electors.

b. The trial court failed to have the court reporter record statements made on audio recordings.

2. Sufficiency of the Evidence

a. Sufficiency of the evidence on attempted election bribery.

b. Sufficiency of the evidence on conspiracy to commit election fraud.

The structure of 1a and 1b (full sentences) does not match the structure of 2a and 2b (phrases). We need to revise 2a and 2b into full-sentence, explanatory headings. The format, italics, should match, too.

Outlining

In creating headings and sub-headings, follow two key outlining rules.

Rule 1: Keep main topics at the same level and keep sub-topics at the same, lower level. So don’t place main headings and sub-headings at a single outline level. For example—

Poor

1. Preliminary Statement

2. Argument

3. The Plaintiff Cannot Prove Consequential Damages.

4. The Plaintiff Cannot Prove Expectation Damages.

5. Conclusion

Better

1. Preliminary Statement

2. Argument

a. The plaintiff cannot prove consequential damages.

b. The plaintiff cannot prove expectation damages.

3. Conclusion

Rule 2: Don’t create a sub-heading unless you have two. If you have only one sub-heading, incorporate it into the main heading. But if your argument or discussion contains only one major issue, it’s okay to have a single major heading for that issue. For example—

Poor

a. The suit is barred by laches.

(1) The suit was brought twenty-five years after the original certificate was issued.

Better

a. The suit is barred by laches because it was brought twenty-five years after the original certificate was issued.

Numbering

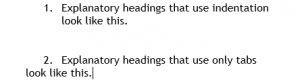

The rules for traditional outlining call for outlines to begin with Roman numerals (I, II, III) and to proceed through letters (A, B, C, and a, b, c) and Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3). If you supplement those levels with Romanettes (i, ii, iii), and parentheses ((a), (b), (c) and (1), (2), (3)), you can create an outline with 7 levels: I. A. 1. a. (1) (a) (i). Two suggestions.

First, don’t write a document (motion, brief, or even a contract) that needs seven levels of headings. Find a way to condense and consolidate; strive to limit yourself to four or even three levels. You’ll be less likely to lose your reader—and yourself.

Second, if you know any level of your outline will go beyond six or seven items, consider using Arabic instead of Roman numerals or romanettes for that level. Roman numerals get harder to decipher the higher they go. I once read a lengthy contract divided into 60 major sections, each designated with a Roman numeral. It was difficult to refer to any particular article because it took too long (or became impossible) to figure out. What’s XLIV?

In my own outlines, I use Arabic numerals and the alphabet, and I still have four levels available: 1. A. (1) (a)

It’s 44 by the way.

_____

To comment, email me.