BY LUIS E. CÁRCAMO-HUECHANTE

It was the winter of 1979. I was already in my fourth year of high school in Valdivia, in southern Chile, when my literature teacher surprised my class by bringing in a record player. As she turned it on, a singular voice came out, with an accent that was difficult to recognize. For those of us listening on that winter morning in the cold and wet public high-school building, the Central American accent coming from the vinyl sounded unfamiliar; nevertheless, it resonated powerfully in our ears.

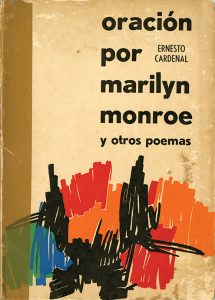

It was the voice of Ernesto Cardenal reciting “Oración por Marilyn Monroe” (Prayer for Marilyn Monroe). Our teacher had decided to have us listen to this single, rescuing it from somewhere in her home, where she had stored and kept hidden an edition of the book Oración por Marilyn Monroe y otros poemas, published in Santiago in 1971.1 The early 1970s were exciting times in Chile, the years of the democratically elected socialist government of Salvador Allende and the Popular Unity party—a political period that was abruptly interrupted by the September 11, 1973, coup d’état. Now, we were listening to the voice of Cardenal in a dramatically different setting, at a time of censorship and institutional coercion in the Chilean school system. These were hard times in the whole country—without Allende, without Neruda, without Víctor Jara, without the hundreds and hundreds of people disappeared or in exile. It was a country ruled by the authoritarian and repressive regime of General Augusto Pinochet and his extreme neoliberal policies. Back to the classroom setting, the principal of my high school was a former member of the Air Force, certainly appointed by the military government to the position; this was common, not only in high schools but in public universities subject to a system of designated principals, usually retired generals or colonels.

By 1979, as has been documented, Chile had experienced the hardest, most repressive period of the Pinochet years. Our teacher, however, had decided to challenge the ruling circumstances by playing in the classroom a poem of strong anticapitalist sentiment by Ernesto Cardenal, a poet associated with a historical process of antidictatorial, popular, and revolutionary struggle. Thus, thanks to the bravery of a teacher, the voice of Ernesto Cardenal broke with our routine of studying a limited range of literary texts, mostly focused on intimate, politically inoffensive themes. In the midst of times of censorship and coercion, it was Cardenal’s verses that awoke me to an unexpectedly revelatory linkage between poetry and social issues, literary writing and collective history.

Listening to “Oración por Marilyn Monroe” gave me the sense that, in those years, it would be in poetry and literature that I would find the echoes and traces of history, rather than in the conservative manuals that were assigned to us. One year later, I found myself delving into the library catalogs as a first-year college student at the Universidad Austral de Chile. One of my first searches was Ernesto Cardenal, which led me to a 1972 edition of his book Epigramas published in Buenos Aires, and a 1969 edition of his Salmos, also published in Argentina.2 These books of poetry, through their anti-Somoza feelings, began to nurture my anti-Pinochet political sensibility, a path that would lead me into the underground politics of the democratic opposition and, more specifically, to join the Socialist Youth in the Chile of the early 1980s.

Requesting and checking out Cardenal’s books was itself a journey of mixed feelings, from the initial fear to the joy of holding them in my hands. They were books that were untouched and resting for years on the shelves, probably like the single that my teacher brought to class—books that sat there quietly and unnoticed by the censors. To be sure, it was not the setting of the American university library where the visitor can directly access the bookshelves. The visitor was dependent on the mediation of the librarian, who had to look at a request card to grab the book for it. Sometimes, checking out books of a poet like Ernesto Cardenal went unnoticed; at other times, a much more knowledgeable official knew what she was delivering to the visitor. Checking out Cardenal’s Epigramas and Salmos left me with the feeling that the librarian knew what she was handing to me, and that she was complicit in my political poetry search. This was the life of reading Cardenal and the life of university libraries in times of dictatorship in Chile. It was in those circumstances that Cardenal’s poetry acquired a broader dimension for me, as a reading of both aesthetic and civic value.

With this remembrance, I would like to situate one dimension of the poetry and intellectual work of Ernesto Cardenal in the context of its reception in the Chile and South America of the late 1970s and 1980s. In this period, Cardenal’s poetic texts circulated under scenarios similar to those of the Somoza years in Nicaragua, especially in those countries of the region subject to military regimes, such as Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, or Bolivia. Reading Cardenal offered us a literary language that spoke of common experiences: of dictatorships, of states of siege, of political violence, of censorship, of sudden nocturnal shots, of fears and silences, but also of clandestine resistance and underground politics, of emancipatory horizons, of the endurance of indigenous cultures, and the broader spiritual and natural life of the universe.

From a literary point of view, the poetry of Ernesto Cardenal arrived during decades in which poets were trapped between the Nerudean paradigm and the antipoetry of Nicanor Parra, between the lyricism of a grandiloquent rhetoric and the radical skepticism of antipoetic discourse. At that point, Cardenal offered us a poetry much more based in the language of history, with documental foundations and ethical impulses. The appealing literary aesthetics of the “exteriorism” coined by Ernesto Cardenal and José Coronel Urtecho invited us to engage the everyday of history in the very terrain of language. As Cardenal explained it:

Exteriorism is the poetry created based in images from the exterior world, the world that we see and touch, and which is, generally speaking, the specific world of poetry. Exteriorism is objective poetry: narrative and incidental, made with the elements of real life and with concrete things, with proper names and precise and exact details and numbers and facts and sayings.3

With this aesthetics of language, Cardenal would help the emerging poets of the 1970s and 1980s to write by engaging the “exterior world” of those years, amid the popularization of television in Latin America, the apogee of consumer society, new waves of urban expansion, along with military coups d’état, political violence, and the launching of free market–oriented economic policies that aggravated social disparities in many countries of the region. Hard times. Poetry helped us.

But, even more, in its amalgamation of historical narratives and denotative style, the poetry of Cardenal resituated the place of the self and feelings in writing, because his poetry also spoke of love, of inner emotions and spiritual values, along with religious quests and scientific references, local occurrences and cosmic mutations, politics and cosmopolitics. Likewise, his poetry invited us to set aside our own stereotypical habits of reading. In times of pressing political matters, while others urged us to only read literary works based in “socialist realism,” his varied publications guided us toward reading across ideologies and aesthetics, across languages, across cultures and times. Through his own poetry, his translations, and the different anthologies he co-edited, Cardenal led many of us to read Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams, Native American poetry, or Latin classics such as Martial or Catullus. In a way, Cardenal set the tone for a new aesthetic and ideological heterodoxy; in other words, a radically democratic view of literature and cultural production that exposed us to readings across the North/South, Western/non-Western divide, from different languages and even from the literary traditions of classical and modern empires.

It is in these terms that I would like to situate the poetry of Ernesto Cardenal, as a poetic and literary art that emerged in a Nicaragua immersed in critical times—a condition that made it resonate in other contexts, in the hard times of my own generation of South American realities. There, it also resounded as an emancipatory “canto” and revelatory “document” of the countercurrents of history, subjectively and collectively.

Today, here and now, it is an extraordinary gift that Cardenal’s papers arrive at the Benson Latin American Collection, in Austin, Texas. And it is likely that once again, Cardenal’s writings, and the ethical, political, spiritual, poetic, and human voice that resonates in them, will accompany us at these latitudes of the planet, in the hard times that seem to be upon us.

Luis E. Cárcamo-Huechante is a scholar of Mapuche origin who grew up in Tralcao, a rural village in the River Region of Valdivia in southern Chile. He is associate professor in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese and director of the Native American and Indigenous Studies program at UT Austin.

Editor’s note: This essay was read by the author on November 15, 2016, at an event celebrating the opening of the Ernesto Cardenal Papers at the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, The University of Texas at Austin. It has been modified slightly for publication in Portal.

Portal wishes to acknowledge Dylan Joy, processing archivist at the Benson Collection, for his extensive assistance providing images for this article and for publicity surrounding Cardenal’s 2016 campus visit.

Notes

1. Oración por Marilyn y otros poemas (Santiago, Chile: Editorial Universitaria, 1971). The first edition of this collection of poetry was published by Ediciones La Tertulia, in Medellín, Colombia, in 1965.

2. The editions available at that time in the catalog of the Universidad Austral de Chile library were Epigramas (Buenos Aires: Carlos Lohlé, 1972) and Salmos (Buenos Aires: Carlos Lohlé, 1969).

3. Quoted by Jaime Quezada in his “Prólogo” for the Antología de Ernesto Cardenal (Santiago, Chile: Editorial Universitaria, 1994); more specifically, see Quezada, 19–20. Author’s translation from the Spanish.